For the first time in my life I have a secretary. If I were a branch manager or assistant V.P. of sales in an honest profession, I might have gotten one sooner. But I am a journalist and we work alone. Finally, though, I have someone who understands the latest iPhone updates, delights in Bluetooth pairing, and can disarm clamshell packaging. I have been sprung from Windows 8 jail because my new helper disabled its improvements and made it work just like Windows 7. If I need to know the name of the second largest river in South America or who started the Surrealist movement, I just ask.

This arrangement, in which I have all the power but choose to surrender myself to another’s precise expertise, fills me with a sense of possibility and future accomplishment. It is bossy of me to use the word secretary, though. I should probably just refer to them as my children.

The dynamic is changing in our house. Our son and daughter once relied on us for everything, but lately they have acquired little talents that we depend on. I’m not talking about chores. They only take out the trash at gunpoint. Plus, anyone can do chores. What has changed is that they’ve joined the load sharing arrangement that used to involve just my wife and me.

Over our 20 years of marriage, my wife and I have come to a corrugated distribution of duties—she submits the medical forms and does the laundry; I pay the bills and mow the lawn. There’s some sense in the distribution—she’s a better cook and I’ve been doing home IT since I stopped my first VCR clock from blinking—but a lot of our task list is the accumulation of chance. When the kids reached a certain age, plunging the toilet became a regular emergency. I was home for the first calamity—achieving a personal best in the two flights to the basement dash. After that I have been Johnny on the spot.

Now we have new members drifting into our labor movement. On a trip to New York, my 11-year-old son and I were headed downtown on the subway. We were late, and without my wife, the family subway Sherpa. (I do airports and we both have specialized knowledge about train travel.) No problem. I figured out the route, the transfer spot, and, since I handle insouciance in our family, no one could accuse me of being a tourist, though it had been 15 years since I’d lived there.

A train approached. We could ignore it, I told my son. I was as confident as I’d been when I warned him about the third rail and explained how to roll under the platform if he fell on the tracks. Fortunately, he had not been listening. He’d become fascinated with the maps, so he explained that we could take this train and still make the transfer down to the Village. Just as I was saying! For the rest of the trip I checked my calculations with him.

I approach the supermarket the way I write. I start in a sturdy enough fashion. I have a list of items written down on paper much like an outline, but once I’m pretty clear on my direction, the wind is in my hair and I’m gaining speed. With writing I can usually get to the end on instinct (we’ll see about that), but this doesn’t work with shopping. I forget to write “chicken” on the list when the purpose of the trip is to collect provisions for chicken dinner. So my wife can expect a text soon after I’ve left the house. Unless I am with my 10-year-old daughter.

When I come home from work, muffins are cooling or bread is rising, because that’s how my daughter unwinds after school. She reads recipes in cookbooks for fun. Instead of a pet, she wants to get a bread starter to keep in the refrigerator and watch over it. So we now have a second person in the house who keeps the kitchen in her head. This means at the market my daughter can be dispatched to retrieve items it takes me twice as long to find. She knows the difference between farfalle and fusilli (and she can make the obvious penne for your thoughts joke). She won’t bring home parsley when she’s been told to get cilantro as some brute once did.

What’s most useful is that she remembers that we’re low on baking powder so we should probably pick up a little. She also improvises. “I know you like coffee and this coffee looked good,” she recently said, throwing a bag into the cart.

When the kids use a vocabulary word precisely or ace a test it’s nice to see, but when they navigate the world in these little ways, it is sweeter. It suggests they’re going to be practical people, which are just the kind of people you want to have around in a pinch. They will be able to manage the little perils of routine living—fixing a flat tire or setting the humidifier so that it doesn’t flood the basement when the season switches from fall to winter. (Running the wet-dry vacuum is my duty.) One of the big questions of parenting is “Are they going to be okay?” These early signs suggest they will be.

The kids are doing more than just picking up the physical load. They’re sharing the mental load too. My daughter is obsessed with camp (we’ve talked about this before, you may remember), so she researched the camps, the flights she’d take, and the dates that worked with her school schedule. That spared us time waiting for Expedia to load, which was nice, but it also freed us from some of the worry that we’d pick the right place for her.

When we take family walks in the woods, the kids love to show us where they cross the creek, or the paths they’ve cut through. That’s what these little bits of mastery are: routes they have carved out of the world that are their own. Stuff that hasn’t come from their parents.

Once we started to rely on the kids, it became a habit. When I couldn’t read the small print on some instructions without my glasses, I instinctively handed the paper to my daughter who saw what I couldn’t. Ordering a movie sometimes requires entering a NORAD level password using only the television remote. You punch the buttons and it doesn’t take, you stab the remote toward the TV and the letter f appears 11 times. You try to hit order and wind up deleting every letter you patiently entered, or you rent Gigli by mistake. None of this happens when my son pilots the remote, so this is now his duty. He also loves any excuse to use a knife or make a knife out of the closest sharp object, so clamshell packaging is also his thing.

These tiny little stitches connect our family in a new way. We now travel as an adventuring party. We use the kids as scouts, or an extra pair of eyes. It’s no longer be careful crossing the street, but what street do we cross? Like characters in Dungeons and Dragons, the little ones—with their distinct clothing and high dexterity—can’t carry heavy weaponry, but they can be dispatched to pick locks and fetch magical rings from small places. Sometimes they can heal during combat. My wife got a brain freeze drinking a margarita and the boy advised her to put her tongue on the roof of her mouth. It eased the pain just as it had with his Slurpees.

Clive Thompson, in his wonderful book Smarter Than You Think: How Technology Is Changing Our Minds for the Better, explains why this shift in load-sharing is so natural. We all take to search engines like Google so easily, he explains, because it is an extension of something humans have been doing for ages. “Transactive memory” is our tendency to store information in those around us to make up for our horrible ability to remember things. I rely on my wife for transactive memory about the names of our friends’ kids, my best friends’ birthdays, and dates longer than five years ago. I now store information in the kids about our household schedule and ever-changing routine. Their schoolwork also makes them a handy reference for quick knowledge on the basic properties of science and geography. I like to drop what they know into my stories to pretend I am more knowledgeable than I am.

The latest development in this shift comes via Minecraft, my son’s current obsession. (He’s building a wind powered Howitzer across the kitchen as I write this.) In Stockholm they use Minecraft to teach kids about the environment and city planning. That’s fine—my son did choose to make the Howitzer wind powered, after all—but the real benefit of Minecraft is that it teaches the kids to teach themselves. The game has no instructions so they seek instruction on YouTube. On Saturdays, we no longer listen to music on the family computer, we listen to some fellow from New Zealand explain how to use Redstone. My son splits the screen to watch the video on one side and try out the construction in the game on the other side.

Then the dishwasher broke. Or, I should say, it got very good at doing something very unhelpful. It pulverizes the food and then spreads the sediment in a fine mist over all of the dishes. The crust makes our glasses look sand covered, like the kind you see at craft fairs where everyone has run out of ideas. Pour yourself a glass of water and one-eightieth of last week’s collected dinners will reconstitute at the top of the glass.

I looked up our brand of dishwasher on Amazon and the reviews were full of swearing, screwdrivers, and petulance. Because the dishwasher is so universally bad, there is a community of the furious. People offer various remedies and I have tried them all. They work for a day or two, but soon enough, I roll back the top rack and it’s Eruption Hour with Dad all over again. During one of these regular seismic events our son looked for an instructional video on YouTube. I assumed this was an attempt to divert from doing his homework, which it was, but he nevertheless found a very good video. A bearded fellow patiently instructed us how to take apart the dishwasher to fish out broken glass.

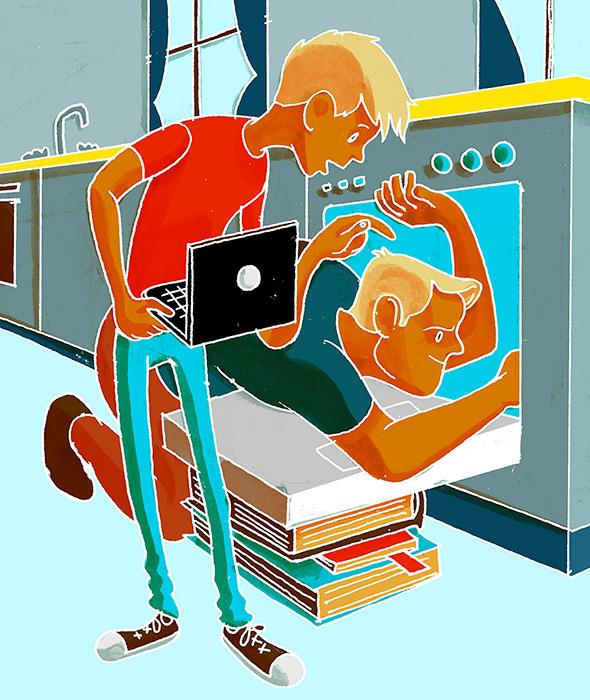

Within minutes we were spelunking inside the thing, removing meaningful-looking parts and making sorties to the basement for new tools. Suddenly, what G.K. Chesterton said turned out to be true: An inconvenience is just an adventure wrongly considered. We now had a project. My son started narrating our moves in a detached voice. It was the same voice my daughter had used when reminding me not to beat the pancake batter too smooth and explaining to me that our oven cooks a little hotter than others—patient, authoritative, and with a hint that you have a lot of old comic books in your attic. It was the generic voice of the YouTube narrator.

Just as I was about to make a dive into the ganglia of the inner dishwasher, my son counseled patience. “First,” he said wisely, “We’ve got to support the door to protect the hinge. Some large books will do the job.” I think they call this reverse mentoring in the leadership seminars; either that or it was incipient mansplaining. He grabbed some art books from the living room and put them under the open door so that my weight wouldn’t break it. We’re really going to be in luck when the wind-powered Howitzer goes on the blink.

Based on this account, you may think that our house is one sleek humming situation of efficiency. No. The load sharing only happens in areas where the kids are enthusiastic. It is very hard to get a job out of them that is not of their own making. So they are still subject to frequent bouts of idleness. When it comes time to do chores, the load sharing activities become the shield. If I start to ask my daughter to pick up her clothes, she’ll have two mixing bowls and drawn butter going before I can finish the sentence. At some point the 10th plate of homemade caramels is just a dodge.

The kids also lack expertise in some of the most basic practical matters. I asked them to shovel the driveway after one of our many recent snows. After a half hour there were signs that shovels had been dragged, but not much more. The kids were making snow angels on the roof of the car, which, now that the snow has melted, has a new constellation of dents.

Good. It’s worrying enough that robots are coming to take our jobs. I’d rather not have the kids make me obsolete just yet, too, though that is what this collection of observations signals. The parenting scale starts out with you taking care of their every need and then the balance slowly shifts. You teach them to become independent so that they can spring into the world in good order, and if you do it right, they not only leave, but leave you dependent on them.

I can already imagine the missing that will be just a little more acute when they’re off on their own and we have to pick up the duties they once delighted in performing. It’s a sort of anticipatory phantom limb syndrome. We’ll be surrounded by dirty plates, cursing the dishwasher, and charging around the parlor in the toils of the remote control. I guess I can always call them for advice. It’ll be a nice excuse to check in. As long as I know how to work whatever device it is that we’ll be communicating on by that time. I suppose that’s what grandchildren are for.