We have a few holiday traditions in the O’Neil family. We gather around the piano singing “I’ll Be Home for Christmas.” My mother pesters me about when I’m going to give her some grandchildren (never mind that she has five). And then later, once all the other guests have gone, we sit around the kitchen table while my mother cries about the saddest moment of her life.

This year, out of the blue, we got to skip the nagging and the crying. My mother had gotten three new grandchildren all at once a few months before, when a long-lost older sister of mine—the subject of her annual tears—materialized in our lives like a plot contrivance. I know it’s a cliché to say that life feels like fiction, but what else do you call it when a mysterious stranger appears from your past?

Four years before I was born, when my mother and biological father were just 15 years old, they had their first child together. This being the early 1970s, the baby was whisked away before she even realized what was going on, during a high school winter recess. Not that she wouldn’t have placed the baby for adoption, but she never had the chance to discuss it, nor had she ever resolved the matter with her own mother, who died in 2009—almost two years to the day before my lost sister returned.

It wasn’t the first time we’d heard of this story; in an argument about 15 years ago, my birth father had wielded the secret against one of my younger sisters, Amber, like a hammer. When Amber got a little older, she made an attempt to track down the sibling, but was stymied by a Kafkaesque paper trail. I figured it was a cold case that would never be solved, and filed it away in the “family secrets” folder. We rarely talked about it, my two sisters and I, and somehow I never connected the dots between my mother’s loss and each year’s fresh new sadness. I was too young, or too self-involved in the way college kids can be, to recognize that my parents were actual human beings with their own personal lives and long histories.

Then in September, my sister tried again. She put in the details—my mother’s maiden name, the hospital where she delivered, and the date of birth—at a site called Adoption Registry Connect. A few days later she got a response. Just like that, the case of the mysterious weeping mother was re-opened. And into our lives crawled a newborn sister: A 38-year-old, newborn mother of three named Marci.

Now that I’ve got a vested interest in the topic I’m starting to find these stories everywhere. Right after Christmas, I came across the story of an adopted young man from Colorado whose family reminded me of my own. He had posted on Reddit that he was looking for his birth parents. Just hours later, with the aid of concerned Internet sleuths, a match had been found. He posted an email response from his mother “I am here and am stunned! I never, ever in a million years, thought you would find me!” Then, just a few days ago, I found another story about a 100-year-old woman who was reunited with her baby after 77 years, via online phone listings.

“With the Internet, searching has just catapulted to a whole new level,” says Leslie Pate Mackinnon, a therapist who specializes in adoption. In the old days, people used private investigators, or somebody knew somebody who might be able to help you find someone—like you were trying to track down a drug dealer. And it came with a similar stigma: The mother, often unmarried and young when her baby was born, might have been considered a slut, and the child a bastard.

A shift has taken place in the past few decades, though, one in which adoptees and parents have begun reframing the way we think about adoption. It’s their own version of the civil rights battle, they say. Groups like Bastard Nation, an advocacy group for adoptee rights, have even tried to take back the slur against those born out of wedlock. “Millions of North Americans are prohibited by law from accessing personal records that pertain to their historical, genetic and legal identities,” their mission statement reads. “Such records are held by their governments in secret and without accountability, due solely to the fact that they were adopted.” Even worse, many adoptees’ birth certificates, the legal document declaring their official existence, are effectively fraudulent, listing their adoptive parents as their birth parents. Until the 1970s and ‘80s, adoption records were top secret, as a rule. Today 11 states have laws on the books giving every citizen access to his or her own birth documents. More states may follow. The suppression of birth-parent identity has become a lot harder with the flow of information online. No one has quantified the phenomenon, says Adam Pertman, author of Adoption Nation and executive director of the Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, but “the Internet is revolutionizing adoption in every way.” Social networking has made reunions exponentially more feasible. “People who have wanted to find each other for a long time now have a process where what they wanted is far easier to achieve than ever,” he says, “but we’ll never have numbers because there is no reporting system.”

After that first message sent through Adoption Registry Connect, my mother and sister began exchanging emails and phone calls with the new member of our family (if that’s even what I’m supposed to call her). My first thought when I heard all of this was how my mother was going to deal with it. My second thought was creepier, but predictable: She’s from Massachusetts; she’s around my age … uh-oh. Dodged a bullet on that one, I’m happy to say.

After we’d established that this thing was going forward, this coming together, Marci and I exchanged a few emails ourselves. “Don’t get sick in case I need a liver someday,” she wrote. I was relieved; she had the wise-ass gene, too. I told her she probably wouldn’t want this liver anyway, as it has been put to extremely good use. Things progressed from there. It felt like flirting—the default setting for getting to know a strange woman over email. We were prepping for a blind date that had been decades in the making.

The romance metaphor came in handy as I tried to talk my mother through her anxious few weeks before the first face-to-face. “How can I love someone I don’t even know?” she asked me. Think of it like you’re going on a date, I said. You both want to like each other already, but there’s no need to come on too strong right away. She may be your biological daughter, but at the moment she’s just a woman whom you’re going to meet, and who may or may not end up being your friend.

When they finally met, my mother found herself surprised at the sight of her lost child, all grown up. Somehow she’d imagined that Marci would have stayed a baby forever. For her part, Marci told my mother she was excited simply to find people in the world who looked like her, which we most definitely do. When I first checked out her pictures on Facebook, I thought I was looking at old pictures of my mother. Or maybe they were of Amber, from a few years into the future? Man, this new Facebook timeline thing is amazing!

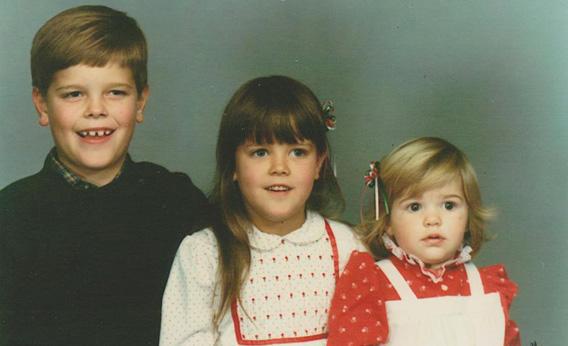

“I saw the similarities right away,” Amber said. “I felt like I was looking at a different version of myself, with blonder hair. She has the same little crooked tooth. Bites her nails like us.” There’s a lot more we have in common, which I learned the first day I met Marci and her own, separate family a few weeks later. She inherited out tendency to carry around a large Dunkin Donuts iced coffee everywhere we go, although I think most people in Boston are born with that. But what about our personalities—would we get along? Would her kids (my nephews, I guess) like me? Did we really have to do this meeting on a Sunday afternoon when football was on?

In stories like this, as in all love stories, the narrative usually ends at the reunion, or the coming together. There’s no follow-up, though. You never get to see what happens next for the guy from Colorado and his new biological family, or the centenarian and her elderly daughter.

“I talk to her regularly, or at least text with her every other day,” my traditional sister says. “I really like her. There are things where it’s like, oh my god, you are my sister—similar personality traits I see in you and [our other sister] Amanda, but I don’t know, it’s hard. I feel like she’s a good friend, but I haven’t said ‘I love you’ to her yet.”

What’s the rush? Right now we’re all still in the early stages of the relationship, with butterflies in our stomachs, trying to put the best version of ourselves forward. No one wants to be the first to say I love you, and no one wants to scare the other person off for wanting it too badly. My mother and sisters have been waiting to find someone a lot like themselves for a long time, and now that they have it—or think they do—they don’t want to spoil everything.

So what comes next? Will it be a true and lasting love, or will we look back on it someday as a brief moment of intense emotion that quickly flattened out? We’ve all felt the sting of relationships that go wrong, and yet we throw ourselves back into them again and again, hoping that this time things will turn out different.

Personally, I’m looking forward to getting this early part over with, and having the honeymoon be over. I want to find out that Marci is not an idealized, alternate-reality version of us, but rather a boring, old, regular human being. That’s what we all are—just a bunch of people who happened to have been pulled together by happenstance of biology and geography. If we can all appreciate one another all the same after recognizing that, then we’ll know we’re family.