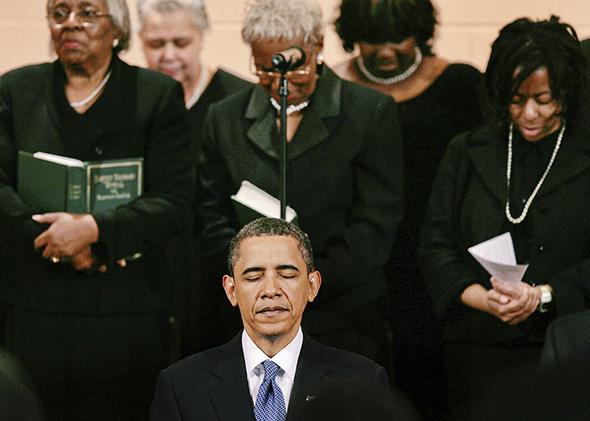

According to a survey taken by political scientist Alex Theodoridis last fall, 60 percent of Americans say that President Obama is either Muslim “deep down” or that they don’t know what the president believes. Among Republicans, a whopping 54 percent believe President Obama is a Muslim—this despite his almost ceaseless declarations of his Christian faith.

It is easy to suspect that this claptrap is an unprecedented display of disrespect. There are certainly unique dimensions to the “debate” over Obama’s faith: his race, his name, his policies perceived as hostile to conservative Christian values, his identity as the first president raised in a non-Christian home, and his longtime membership in an inflammatory pastor’s church, to name a few. But historian Gary Scott Smith’s new book Religion in the Oval Office, which traces the religious lives of 11 presidents from John Adams to Obama, makes clear that dark rumors about a president’s secret faithlessness are nothing new. The hefty new volume and its predecessor, Faith and the Presidency, point to a startling suggestion: No president in history has been Christian enough for the American people.

Thomas Jefferson arguably had it the worst. In the election of 1800, ministers spread rumors that Jefferson held worship services at Monticello where he prayed to the “Goddess of Reason” and sacrificed dogs on an altar. Yale University president Timothy Dwight warned that if he became president, “we may see the Bible cast into a bonfire.” Alexander Hamilton asked the governor of New York to take a “legal and constitutional step” to stop the supposed atheist vice president from becoming head of state. Federalists who opposed him called him a “howling atheist,” a “manifest enemy to the religion of Christ,” a “hardened infidel,” and, for good measure, a “French infidel.” As Smith describes it, insults like these were issued forth from hundreds of pulpits in New England and the mid-Atlantic. When Jefferson won the election, many New England Federalists buried their Bibles in their gardens so the new administration would not confiscate and burn them.

Jefferson, a (possible) deist well known now for his sliced-and-diced Jefferson Bible, may seem like a natural object for such paranoia. But take George Washington, whose reputation of piety has been a major element of his popularity in the centuries following his death; one persistent myth has him kneeling in prayer in the snow of Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. During his own time, some doubted the robustness of his faith. Congregationalist clergyman Samuel Langdon, a former president of Harvard University, urged him to publicly proclaim he was “a disciple of the Lord Jesus Christ.” The president demurred. Three decades after Washington died in 1799, Episcopal bishop William White fretted he couldn’t bring to mind “any fact which would prove” that the country’s first president believed “in the Christian revelation,” other than his regular church attendance.

The ironic thing is that none of the Founders neatly fit the mold of “deep down” Christian in a way that would satisfy the conservatives who veritably worship them today. This is not breaking news, but Smith’s books are valuable reminders. Washington attended church only sporadically, apparently spent very little time with the Bible, and said very little about Christianity or about Jesus in public or private. John Adams rejected the divinity of Jesus and the infallibility of the Bible. James Madison never joined a church, implied all religions worship the same God, and said almost nothing about his own beliefs after his mid-20s. They were happy with a certain level of civil religion—vague public references to Providence and the Creator, national days of prayer, and so on. But there’s a reason these men were statesmen and not ministers. Obama, with his explicit public references to his personal belief in Jesus’ salvific death and resurrection, and stories about the Holy Spirit interceding in his prayers, is much more identifiably Christian than any of the founders.

Indeed, few of them were spared the suspicions of their own citizens. Adams later attributed his loss in the election of 1800 to false rumors that he was a Presbyterian. “The secret whisper ran through all the sects, ‘Let us have Jefferson, Madison, Burr, anybody, whether be philosophers, Deists, or even atheists, rather than a Presbyterian,’ ” he wrote. (He was actually a Unitarian.) Madison, hailed then and now as a champion of religious liberty, prompted one “Bible Christian” to grouse that one of his proclamations of a day of prayer contained nothing that would bother “a pagan, an infidel, [or] a deist.”

Through the 19th and 20th centuries, devoutly Christian Americans continued to question their leaders’ religious bona fides. In an 1831 visit to the White House, a Methodist pastor from Baltimore ostentatiously boomed out a prayer that Andrew Jackson would be converted. William McKinley, a Methodist who Smith calls “one of America’s most intensely religious presidents,” weathered rumors that he was Catholic, including that his children had attended Catholic prep school. (In fact, they both died before age 5). Actual Catholics had it much worse: 1928 Democratic nominee Al Smith arguably lost the election because of fear-mongering over a “Romanized” republic. (John F. Kennedy, the only Catholic president so far, also faced open speculation that he would be a puppet of the Vatican.) Harry Truman, a Baptist who while in office exhorted Americans to go to church, was frequently lambasted for not attending frequently enough himself.

On and on it goes. And if anything, we can expect populist religious pressure to worsen in the years to come. Today’s candidates face not only hysterical demands from the right to prove their private beliefs—an impossible task—but new prodding from the left to renounce traditional religious orthodoxy. A recent Salon screed blasted the “supposedly God-fearing clowns and faith-mongering nitwits groveling before Evangelicals and nattering on about their belief in the Almighty” and pushed candidates to “clarify” whether they endorse Levitical rules for punishing gay people and sex workers. (I’ll go ahead and answer for them: They don’t. Here’s a conservative evangelical church’s explanation for why Christians are not bound by Mosaic Law.) Last year on the Daily Show, Bill Maher optimistically declared Obama a “drop-dead atheist” whose decadeslong church membership was just a political ploy.

The current possible slate of presidential candidates includes a Catholic convert from Episcopalianism (Jeb Bush), a former Mormon (Marco Rubio), a Methodist (Hillary Clinton), and an ordained Southern Baptist minister (Mike Huckabee), to name a few. Who knows what’s in their heart of hearts, or how cultural or political pressures inform their expressions of belief? The only sure thing is that the next president’s faith won’t be good enough for everyone. It’s the American way.