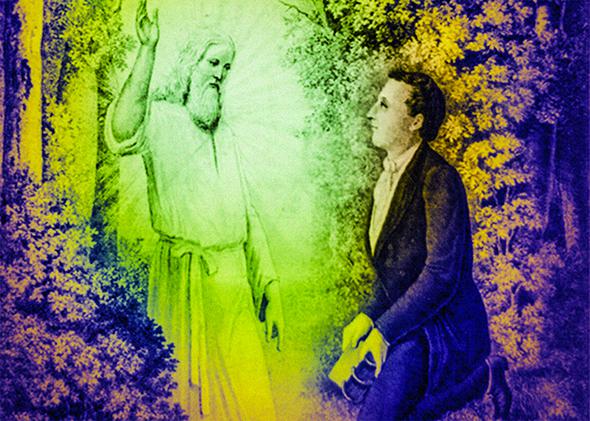

For Mormons, the recent spasm of media attention to church founder Joseph Smith’s polygamy was the stuff of century-old nightmares—painful evidence that, even after 100 years of performing conservative American-ness so cheerfully that it can appear paradoxically creepy, Mormons are still perceived as strange and secretive. News outlets seemed downright eager to put “Mormon” and “polygamy” together in headlines, and many publications repeated the not-entirely-accurate assertion that Smith’s multiple marriages—possibly as many as 40, one to a girl of 14, and some to women married to other men—were being acknowledged by Mormon leaders “for the first time.” Such stories rehashed the narrative that has framed the American relationship with Mormonism since its beginnings, one of estrangement and persecution followed by difficult, halting steps toward assimilation. Polygamy is always at the center of this narrative, despite the fact that Mormons have now not practiced polygamy for almost twice as long as they did practice it.

But the three new essays that prompted this latest wave of attention—a total of about 10,000 words outlining the history of what was called “plural marriage” by the Mormons—highlight an unlikely fact about life after the “Mormon Moment,” that recent stretch when, thanks largely to the presidential campaigns of Mitt Romney, Mormonism was in the news on a daily basis. That moment is now, most everyone agrees, over. In its wake, something unexpected has become clear: The relationship between Mormons and non-Mormons hasn’t really changed that much, despite all the attention and scrutiny. In fact, that outside attention had a more significant impact within the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints than it did on relations between its members and their fellow citizens. While the outside world continues to perceive Mormons in largely the same old terms, the culture within Mormonism is changing, and more Mormons, including some in the upper ranks of the church, are coming to terms with the faith’s sometimes troubled history.

When Romney’s 2008 and 2012 campaigns for the presidency brought unprecedented attention to the LDS church, Mormons hoped that becoming better known would mean becoming better liked. (Mormons are nothing if not relentlessly optimistic.) In their new book, Seeking the Promised Land: Mormons and American Politics, political scientists David E. Campbell, John C. Green, and J. Quin Monson report that “just as the 2012 presidential race was heating up, the Pew Mormons in America survey reported that 68% of Mormons thought their fellow Americans did not consider Mormonism ‘mainstream.’ But a nearly identical number, 63%, also indicated that their fellow citizens were becoming more accepting of Mormons.” This quintessentially Mormon hopefulness is not supported by the data, however. The same Pew survey that reported Mormons’ belief that they were becoming more accepted reported that, when asked to choose a single word to describe Mormons, “cult” was the most frequently offered response, with “polygamy,” “different,” “strange” and “odd,” and “crazy” also in the top 25 responses.

The novelty of Romney’s own Mormonism wore off and became a relatively unimportant factor in the 2012 race—but his campaigns seem to have done little to change American perceptions of Mormonism more generally. This despite an endless stream of stories in the press on topics ranging from Mormon feminism to Mormon businessmen (and it is always men) to Mormon nudists. This coverage, though, had another, presumably unintended effect: Media attention was a megaphone for the voices of Mormons who might ordinarily find themselves on the fringes of their congregations—academics, feminists, LGBTQ Mormons, and Mormons questioning their own beliefs. Mormonism’s strongly top-down flow of information and power means that these voices are usually not heard in the top echelons of the hierarchy. But when they were suddenly in the pages of the New York Times and on The Daily Show, they were hard to ignore.

And reporters’ interest in these somewhat marginal Mormons continued even after the campaign ended. Mormon feminist activism has been extraordinarily well covered, given the relatively tiny fraction of Mormon women who identify as feminists. Perhaps in part due to this media amplification, the church has been responding to decades-old concerns of Mormon feminists with relative alacrity. Mormon women prayed in the church’s semiannual world General Conference for the first time last year; the Church Educational Service, which manages professional teachers of religious programs for Mormon teens, now allows women to continue their employment after having children; policy about menstruating women’s participation in temple rituals was clarified; and, in a change that is likely to have wide-ranging and long-lasting impact, Mormon women may now serve missions at age 19, as their male counterparts have done for decades, rather than waiting until age 21, when professional and marital commitments are more likely to interfere. These may seem like small—and, perhaps, absurdly belated—adjustments, but they represent changes that Mormon feminists had been advocating unsuccessfully in print since the 1970s and online for a decade. The fact that they are occurring so quickly now suggests that media attention driven by the Romney campaign was more effective in making these concerns known to leaders than Mormon women’s efforts alone.

There were, of course, limits to this effectiveness. It was rumored that the plan to assign women prayers at General Conference were nearly scuttled by concerns about appearing to bow to pressure from feminist activists and journalists. When a group advocating priesthood for Mormon women sought media interest to draw attention to its cause, the strategy seems to have backfired: One of the group’s leaders, Kate Kelly, was excommunicated for her efforts, which included organizing two highly publicized collective actions (the group eschewed the term “protests”) requesting admittance to a meeting of the all-male priesthood.

Around the same time that Kelly was excommunicated, the host of the popular Mormon Stories podcast, John Dehlin, was threatened with disciplinary action as well. Unlike Kelly, he was not excommunicated, perhaps in part because he initially kept details of his interactions with church leaders out of the media.* But his emergence in the past few years also reflects broader changes in Mormon culture. His podcast has served a pastoral function for Mormons in “faith crisis,” and he was instrumental in creating and distributing a 2011 survey probing the causes named by “Disbelievers” for their loss of faith. High on the list of those causes was “I studied Church history and lost my belief.” Polygamy was ranked first among historical issues that precipitated a loss of faith. A front-page New York Times article mentioned Dehlin’s survey and featured Hans Mattson, a church official in Sweden who had lost his faith over questions including those about Joseph Smith’s polygamy.

It’s possible to read the disciplinary actions against Kate Kelly and John Dehlin as a reprise of the much-discussed 1993 excommunications of six Mormon intellectuals, as yet another iteration of the church’s inability to tolerate dissent or criticism. Certainly some of the subject matter that Kelly and Dehlin have written and spoken about echoes the topics that caused trouble for Mormon thinkers in the 1990s. But Dehlin’s interlocutors on troublesome topics have not faced censure from the church, and Mormon feminists remain active and vocal online, at conferences, and in magazines and journals, with no reprisals. Church leaders have become dramatically more open to scholarship and criticism directed to an internal audience in the years since 1993, as evidenced by the proliferation of conferences and publications devoted to serious scholarship—even quite critical scholarship—on Mormonism. The new essays on the church’s website, especially the essays on polygamy, reflect this openness to previously suspect kinds of work. The footnotes of the essays are a quiet acknowledgment of the work of scholars and publications that were once deemed beyond the pale.

Dehlin’s and Kelly’s activism seems to have worried Mormon leadership not because it expressed criticism of Mormon culture or practice, but because it worked in the uneasy space of Mormon assimilation with American culture in a way that the hierarchy could neither anticipate nor control. Neither Dehlin nor Kelly was disciplined for expressing new ideas; instead, they faced opprobrium for expressing those ideas directly to outsiders. Deliberately leveraging the press was apparently perceived as disloyal, in a way that has painful resonance with Mormons’ history, going back to the reports (and caricatures) of Mormon life that regularly appeared in the national press throughout the 19th century. Even after polygamy was outlawed as the price of the church’s continued survival and Utah’s statehood, Utah’s monogamous Sen.-elect Reed Smoot was the subject of three years’ worth of acrimonious hearings, relentlessly reported in humiliating newspaper stories and cartoons, before finally being allowed to retain his seat. While things have obviously improved since then, even at the beginning of Romney’s second run for the presidency, Gallup polls showed that around one in five Americans admitted that they would not vote for their party’s nominee if she or he happened to be Mormon, regardless of his or her policy positions or personal qualifications. This number was virtually unchanged from the time of Mitt’s father’s run for president in 1968.

Given this history, Mormons’ continued eagerness to be accepted as fully American, as “mainstream,” may seem a little desperate. But it is also testament to the enduring appeal of an idealized America that lives up to its pluralistic creed. Even as Mormons recognize their continued, unwilling exile from that America, we are affirming those ideals by learning, haltingly, to cope with our own messy history and to tolerate, albeit imperfectly, difference and dissent within the faith.

*Correction, Dec. 3, 2014: This article originally misstated that John Dehlin agreed never to speak with the media about his church disciplinary process. He did not make such an agreement. (Return.)