I’ve been to many Seders in my nearly three decades. There was the one where our hosts had us march around the block with sacks of matzo singing “Avadim Hayinu,” (“We Were Slaves”)—they were going for Exodus verisimilitude. There was the one where the four questions were recited in more than 10 languages—concluding with my septuagenarian uncle’s rendition in a perfect and crisp Ladino. But while each family brings its own traditions and spin to the meal, there’s one constant: No one wants to get stuck reading the passage about the wicked son.

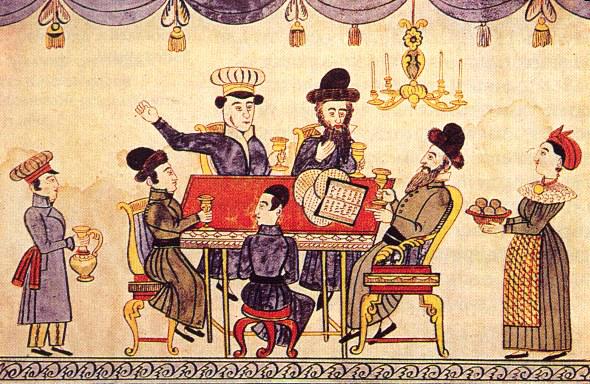

There are many fours in the Haggadah—four glasses of wine, four questions, four sons, four words of redemption—and much of the Seder is spent discussing them. In fact, the entire Seder is really one big lesson, with the Haggadah serving as its textbook, a way for one generation to teach the next about the Exodus from Egypt. Early on, after the children ask the four questions, we read of four sons referred to in the Bible (though not by name): the smart one, the wicked one, the simple one, and the one who doesn’t even know how to ask. The Haggadah presents these four figures as a way to kick off a discussion of the Passover story.

The smart son asks what laws God commanded us to obey, and the parent is instructed to answer by explaining the laws of Passover. (This has always struck me as a pretty lousy question: Do your own research, smart son!) The simple son simply asks, What is this?—that is, what are we doing here at this Seder? Not a bad question, given the peculiarities of the Seder meal. As for the son who doesn’t even realize he should be asking questions, or doesn’t know how to ask, the tradition is to initiate the conversation for him by telling him the story of Exodus.

This leaves the wicked son, who asks, What are all these things to you? The Haggadah brands this question as evil because the son separates himself from the group, by asking what the observance of Passover means to you. The question is interpreted as a rhetorical one, an affront to the entire notion of holding a Seder and, by extension, practicing Judaism. As such, the prescribed response is pretty abrasive: The wicked son is told that had he been in Egypt he wouldn’t have been redeemed, and participants are instructed to “blunt his teeth,” a funny translation of a Hebrew idiom that has always felt a bit more violent than necessary, especially for a question that strikes me as thoughtful and important.

Somewhere in my late teens or early 20s I realized that despite my aspirations to be the smart one, I had more in common with the wicked son. It’s not that I reject Jewish practice or belief. I just don’t think his question is wicked, even if the authors of the Haggadah clearly intended it to be.

I prefer to refer to the wicked son as the challenging child, a more alliterative, gender-neutral, and helpful way of looking at this character. As for her question, it sounds less evil to me than sensible. The idea of searching for meaning in practices, and understanding their motivations, is a natural one. Challenging the reasons behind tradition, and the logic underlying the holiday’s restrictions, can only lead to greater understanding and more honest practice. Whereas the smart son merely asks for, and receives, the law, the wicked son asks for the reasoning underlying those laws.

While there’s no denying that tradition and laws are the backbone of religion and society, both religion and society need challengers if there is to be any progress. Often, such a challenger is branded, at first, as evil, only later to be recognized as a visionary—think of Sarah Schenirer, or Isaac Newton. The questions posed by the challenging child are not a rejection of practice, as I interpret them. They’re a way of giving meaning to action. They’re not an attempt to stand apart from the group—they’re an attempt to understand what, exactly, the group stands for. To dismiss the question is to suggest that Judaism is a faith that doesn’t permit skepticism—a position I think most Jews would reject.

This may seem like a trivial rereading of an often rushed-through bit of the Haggadah, but there’s more at stake here. There are questioners in Judaism today who are asking the hard questions and being ostracized as a result. Take the recent discussion about women laying tefillin. Like the wicked son, these women have taken seats at the table. They want to be part of the conversation. But their questions are only met with shouts of “enemy.” The child isn’t the problem, it’s our response that is.