This is an excerpt from My Mother’s Bible by Walter Kirn, out now as a Byliner.com original.

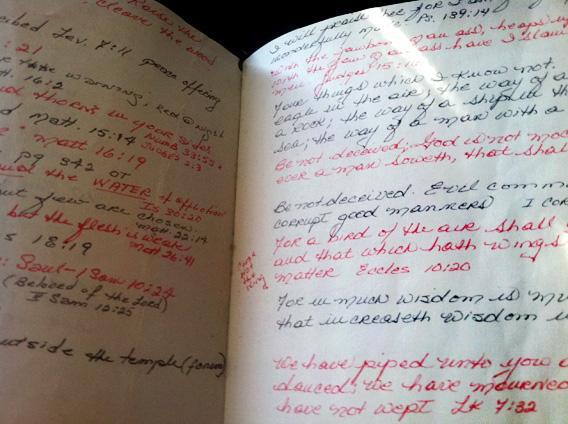

Two Augusts ago, my mother, Millie Kirn, a 71-year-old retired nurse, died suddenly of brain infection. While going through her things a few days later, I found a book I hadn’t know she’d owned: an oversize King James Study Bible whose pages were covered with handwritten notes. My mother wasn’t conventionally religious but she was immoderately literate, an old-fashioned freethinker and lover of the classics with a skeptical, irreverent turn of mind. In my grief, as a way of feeling close to her, I opened her Bible and began to read—my first true and thorough attempt to study the scriptures.

The result was a conversation through the veil about stories I thought I understood but didn’t, most of them stranger than I’d ever suspected, with lots to say about parents, children, love, and love’s dark echo, anger. I put my own jottings together in a small book, My Mother’s Bible, which captures, I’d like to think, my mother’s spirit. People can be so neglectful of each other and of their own heritage—then death intrudes. Conversations we wish that we’d had earlier are had too late. This is part of one of those.

Minds of Their Own: Genesis, Chapter 3

At last I think I understand: The story of the Fall is about a drug bust and its aftermath. It begins by discussing the prohibition of a potent psychedelic substance: a plant or a fruit that grants those who ingest it personal access to divine capacities. Most damningly to those who wrote the story (with the goal, I suppose, of consolidating their hold on law-giving and other “holy” prerogatives), this prohibited substance sensitizes the mind to the presence of “good” and “evil,” essentially making priests of those who take it—and rendering other, conventional priests redundant. The closest I came to this feeling in my own life was the year I dropped LSD about an hour before a Thanksgiving dinner at our farm. At some point I looked around the crowded table and saw what I took to be thoughts, like wisps of fog, moving in and out of people’s heads. What the thoughts were, I wasn’t sure, but some were beautiful and others ugly, which caused people’s faces to change accordingly, sometimes tightening them, sometimes relaxing them. What astonished me was that the thinkers were unaware of this, emitting strange energies known only to me.

Rather than live for all eternity in frustrating look-but-don’t-touch proximity to the alluring, magical botanical, the humans decide to go ahead and take the stuff. Like God himself, whom they supposedly resemble, they’re restless creatures, unable to keep still, so it’s hard to fault them for their choice. Had they done the impossible and remained incurious, the need for a Bible, or books of any kind, never would have come about, since life in hammocks eating fruit and petting the animals as they pad by hardly warrants recording. Life would have been like one of those mass Christmas cards that some of my relatives sent out every year. Life is good and everyone is healthy. They all love their jobs and are doing well in school. We hope and trust that it’s the same with you.

As it happens, the creature who turns the humans on, rendering existence existential and consciousness something more than mere awareness, dwells as close to nature, to the soil, and as far from hierarchies and sky gods as it is possible to get. The serpent, like the tree itself, is attached to the earth, to the planet’s deepest energies, drawing them upward into the social realm and introducing some texture to experience. If this voluble reptile had not existed, God might have had to invent him at some point simply to dispel the dreariness of permanently, uneventfully beholding a pair of handsome, smug immortals with nothing to talk about, even between themselves, besides their own wonderful virtue and obedience and the futility of the serpent’s salesmanship.

The rest of the story concerns the humans’ sentence for the crime of unleashing their latent godliness through commerce with the psychoactive plant. Banishment and hard labor are some of their punishments. And shame, of course, the fiercest lashing of all, because it’s self-administered. What they don’t do, strangely, is realize they’ve been set up and lay appropriate blame on the Creator, who needn’t have forbidden anything or planted booby traps of any kind. He could have made disobedience impossible rather than virtually inevitable. My mother made a note of this and added that “God gives the order re: ‘the apple’ before Eve is created.” It wasn’t God that Eve brushed off, this tells us, but Adam, a rather less impressive figure who failed to utter one memorable remark during a lifespan of more than nine hundred years. If God had deigned to speak to Eve directly, showing her a little more respect, she might have been more inclined to heed his wishes.

Photo by Amanda Fortini.

How strange, how unexpected and how strange, that the establishing myth or narrative of Jewish and Christian morality deals not with murder, deceit, or theft but with expanded consciousness, with tripping. How strange to learn that our original sin—at least in the minds of those who wrote the Bible—was closer to taking mushrooms than taking a life. Was the appetite there all along? I’m guessing it was. I’m guessing Eve’s choice to get high was not a choice for her.

I wish I could have discussed this with my mother. Her last job as a nurse was at Hazelden, a rehab clinic, where she met many celebrated drug addicts, some of them great artists. Her favorite was Truman Capote (“the little genius”), whose terrible pill-and-booze habit destroyed him. After he died, my mother revealed to me that she’d asked him during his treatment if he had any advice she might pass on to me about becoming a writer. (I was in college when they spoke.) “Not at all,” Capote said. “Tell him you either are one or you aren’t.”

I think Eve was a writer.

And Adam wished he were.