The Book of Mormon, a musical from the creators of South Park, won a Grammy for best musical theater album on Sunday, shortly after topping the Broadway box office for the first time. But in the following excerpt from his new book, The Mormon People: The Making of an American Faith, historian Matthew Bowman argues that both The Book of Mormon and the recently revived Angels in America miss something crucial about the faith and its culture.

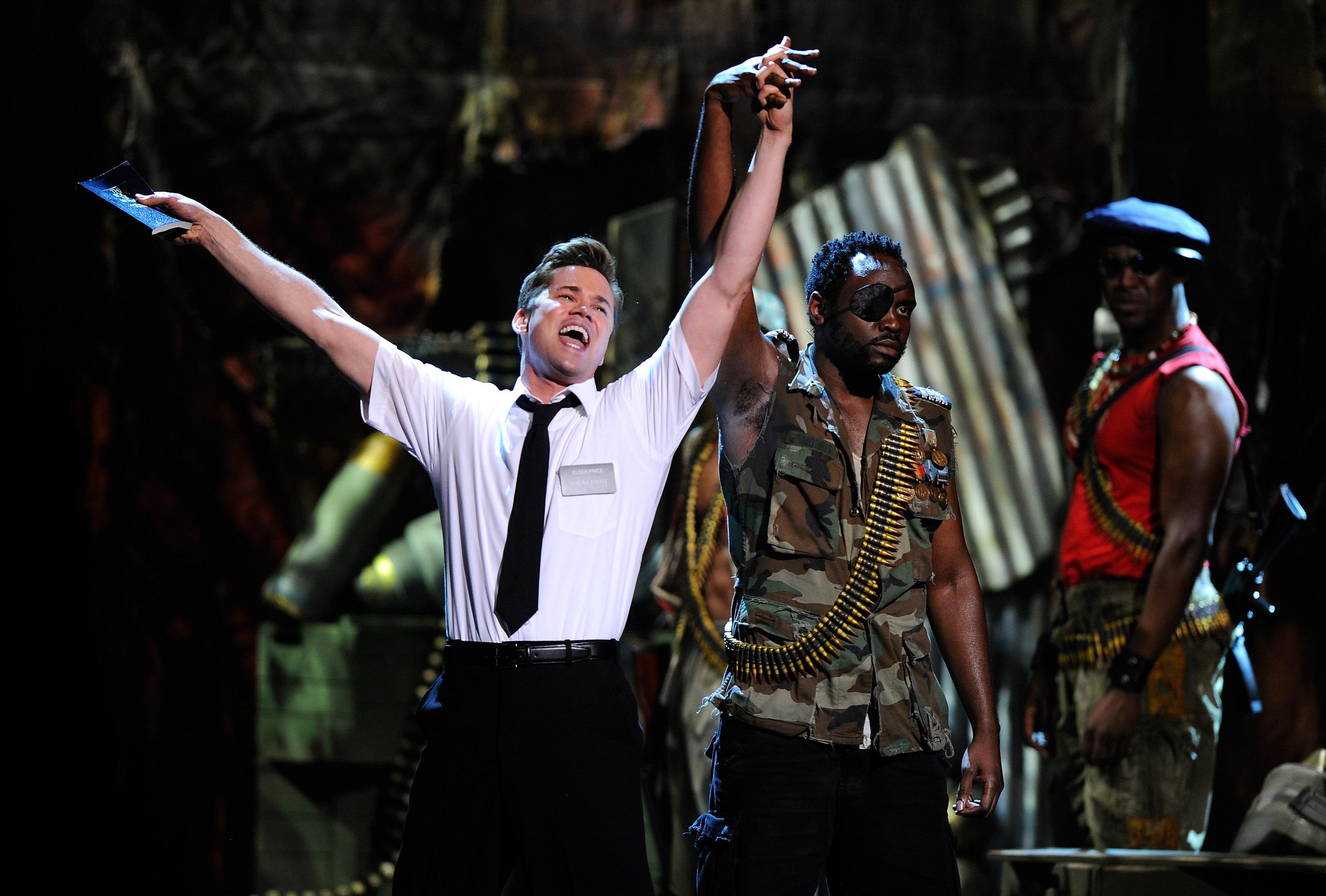

“Hello! My name is Elder Price, and I would like to share with you a most amazing book!” sings the actor Andrew Rannells to the audience of the Eugene O’Neill Theater in New York City. In March 2011 the tart musical satire The Book of Mormon opened on Broadway to largely rapturous reviews and sellout crowds. It received 14 Tony nominations and 9 wins. A recent Pew survey shows that many Mormons believe a gulf stands between themselves and American culture; after spending much of the 20th century finding ways to make America’s virtues their own, they discover by the end of the century that propriety, rectitude, and dogged cheerfulness seem not to gain them the admiration they once had. But in The Book of Mormon, the fresh-scrubbed diligence of Mormon missionaries is a mark of naïveté, repression, and foolish optimism. The childish buoyancy and faith of a pair of Mormon missionaries sent to war-torn, disease-ridden Uganda blinds them to how monumental the challenges they face really are, and their solution—the religion of the “all-American prophet” Joseph Smith, as one song labels him—seems hopelessly, even hilariously, inadequate.

Many reviews credited the musical with an underlying fondness for Mormonism. Sweetness was often the word of choice. And indeed, the musical’s Mormons are genuine, entirely without guile, thoroughly and unbelievably committed to the preposterous notion that their bizarre faith can make people’s lives better. When the bumbling Elder Cunningham inadvertently produces a wildly bowdlerized version of Mormonism, the musical’s African characters embrace it wholeheartedly because it directly addresses—though can hardly hope to solve—the problems of AIDS, poverty, and war. Mormons’ ludicrous innocence, the musical’s scribes appear to be saying, is perhaps slightly mitigated by the fact that it makes them extremely, almost impossibly, nice.

In light of the history of the relationship between Mormonism and American culture, the transformations that produced the Mormons of The Book of Mormon seem rather staggering. From a looming threat to the American republic, a religion that Americans feared would inculcate the perversity of polygamy, the death of democracy, and raving heresy, Mormons have become at the dawn of the 21st century the living image of bland, middle-American tedium, so wed to awkward cultural conventionality that their strange beliefs seem a curious accessory rather than a serious challenge to American assumptions.

To some Americans who still find Mormonism’s claims about miracles and golden plates and prophecy scandalous for reasons of orthodoxy or skepticism, this stereotype is in fact frustrating. John Lahr of The New Yorker complained that the musical gave Mormon doctrine too much of a pass, lamenting that its creators “ultimately lack the courage of their non-conviction,” and failed to pillory Mormons for the “surrealistic godsend for comic writers” that constitutes their theology. To Mormons themselves, always sensitive to mockery or slight, the musical’s version of Mormonism is, at the least, an improvement. The church’s official response to the musical consisted of a single sentence, so dry and understated as to make one wonder if the Mormons, finally, might be in on the joke: “The production may attempt to entertain audiences for an evening, but the Book of Mormon as a volume of scripture will change people’s lives forever by bringing them closer to Christ.”

It is too easy, however, to mark off the history of Mormons in binary: now and then, polygamous visionaries and monogamous Puritans, social revolutionaries and dour Republicans, 1840s Nauvoo and present-day Provo, Utah. The Mormon embrace of American virtues was real because it emerged as much from the processes of their own beliefs as it did from outside pressure, and as such it was always directed to their own purposes first and to those of the nation second. At the heart of the faith a radical and transformative vision still lurks, and the Mormons made America their own as much as they made themselves Americans.

Tony Kushner’s 1991 Pulitzer Prize–winning play Angels in America, sensing these discontinuities, consequently uses Mormonism as a symbol to explore what America might have been and what it is struggling toward. Kushner’s Mormon characters fill the borders of the stereotype that The Book of Mormon skewers, but on closer investigation, they are the musical’s bright-eyed missionaries in negative, afflicted with the same conventions but lacking any sense of naive idealism. A dull, conventionally ambitious, right-wing attorney and his detached and bored housewife, these Mormons have no sense that America might be anything other than a cold, cutthroat world of 1980s capitalism, cultural conservatism, and self-repression and certainly no inkling that their faith might offer any alternative.

For Kushner, Mormonism’s radical mythology is distinct from the dreary way of life slowly smothering his heroes, and it proves an astoundingly revitalizing force. Angels, the descendents of Moroni, crash through roofs into bedrooms, Mormons converse with suddenly conscious animatronics of their pioneer ancestors who remind them of the devastating sacrifices of the Mormon trail, and gradually, gradually, Kushner’s characters become aware that there is a life of pain and intensity and passion beyond the world they know, though few may ever reach it.

But both the riotous musical and Kushner’s brooding black comedy present faith defanged—Mormonism shorn of its revolutionary qualities. The Mormons of The Book of Mormon offer no challenge to modern American life. Their beliefs are patently ridiculous, amplified, and exaggerated in the song “I Believe” to emphasize Mormons’ apparent utter detachment from reason and rationality. These Mormons are a national entertainment, an amusing foil to a satisfied modern and secular society; they seem hardly capable of keeping their own church running, let alone staking any ambitions upon the nation. Kushner’s contemporary Mormons are the grim storm troopers of American capitalism, unthinking servants of all that is wrong with the status quo, barely conscious of their own once marginal heritage. To some evangelicals, they are dangerous heretics; to many Republicans, they are merely reliable voters.

All capture a part of what it may mean to be Mormon in America today, but none quite grasp the multifaceted ways in which Mormons currently define themselves and the strength with which their religion still creates for them a profoundly radical world. Mormons still cling to a determined supernaturalism. Though thoroughly integrated into the mores and functions of contemporary American life, they remain committed to at least the proposition that their prophet, inevitably these days a benevolent elderly man neatly dressed in a conservative suit, may indeed receive divine revelation that could uproot their lives in an instant. They believe that one day they may yet be asked to give up American capitalism and return to Joseph Smith’s vision of economic consecration. Some fear that they may one day be asked again to practice polygamy. Nearly all believe that Joseph Smith truly was visited by an angel in upstate New York nearly two hundred years ago and that the priesthood of God held by the great figures of the Bible stands available to them, thoroughly average dentists and attorneys and businessmen today. Mormon fathers go home from these stolidly conservative occupations, consonant with Mormon men’s general commitment first to be good economic providers, and lay their hands on the heads of their children and invoke the power of God to seal blessings upon their heads.

Their faith in the existence of the metaphysical world that empowers their blessings and seals their eternal relationships with their wives and husbands, parents, and grandparents drives the Mormons to devote hours a week to making that world real in the congregations of their church, to pay to spend eighteen or twenty-four months of their lives determinedly carrying copies of the Book of Mormon to any of hundreds of places across the globe, to devote weekends each month to attend the temple and perform proxy ordinances for their 17th-century ancestors. Their devotion to families, though it may be functionally deeply conservative in contemporary American politics and culture, in fact gestures toward the profound and radical vision of community that draws them toward salvation. While the story of Mormonism in America is in many ways the story of the Americanization of a radical religious movement, that radicalism survives, however muted, in the vision of Zion pronounced by Joseph Smith and preserved by modern-day Mormons.

Excerpted from The Mormon People by Matthew Bowman Copyright © 2012 by Matthew Bowman. Excerpted by permission of Random House Group, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved.