The clothing retailer American Eagle posted an advertisement for spray-on jeans on its website this week, calling the product “our skinniest jeans ever.” The ad appears to be a prank, but painting models is now old hat. Is it legal to appear in public wearing nothing but body paint?

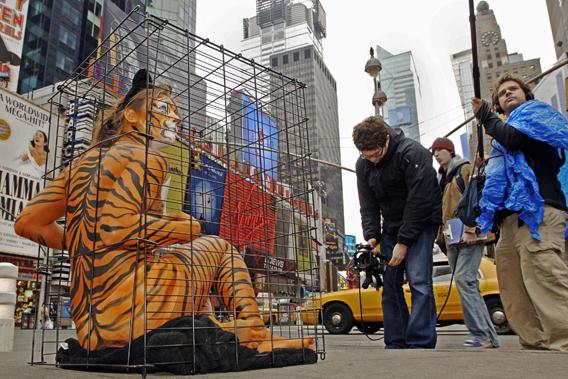

It’s a gray area. Most anti-nudity laws are silent on body paint, leaving police to make judgment calls. A decade ago, body painters were arrested with some regularity. In 2000, for example, a Chicago woman who painted herself to resemble a tiger in protest of a circus was arrested for public indecency, even though she was also wearing panties and pasties. But as early as 1995, Entertainment Tonight aired an interview with a model wearing nothing but paint and faced no repercussions. Local police are also showing increased restraint. Recently, officials have stood by as body-painted (or even completely nude) environmentalists rode their bicycles through American cities in protest of our dependence on oil. In 2011, New York City officials allowed artist Andy Golub to paint otherwise nude models in public spaces as long as his muses wore bikini bottoms during daylight hours. Public officials can still be pushed too far, though, and rampant body painting in a locality often leads to a tightening of laws. Following a proliferation of nearly-nude or body-painted coffee baristas, the city of Federal Way, Wash., amended its laws to make clear that “body paint, body dye, tattoos, latex, tape, or any similar substance applied to the skin surface, any substance that can be washed off the skin, or any substance designed to simulate or by which by its nature simulates the appearance of the anatomical area beneath it” would not be considered equivalent to clothing.

The Federal Way ordinance is an exception; state and local anti-nudity laws are usually deliberately vague. Many statutes use the word expose to define what constitutes nudity. San Francisco’s 2012 anti-nudity law, for example, notes that a person “may not expose his or her genitals, perineum, or anal region.” It doesn’t make clear whether body paint is an acceptable covering, giving police broad discretion in deciding when to arrest, when to caution, and when to ignore painted exhibitionists in the city. Other anti-nudity laws are more specific, seemingly giving body painters a pass. The Code of Federal Regulations, in banning public nudity in certain national parks, notes that nudity is the failure to “cover with a fully opaque covering [the] genitals, pubic areas, rectal area or female breast below a point immediately above the top of the areola.” Several states, including Idaho and South Dakota, use similar definitions of nudity. (It should also be noted that many states prosecute public nudity only if paired with lewd or lascivious behavior, which would likely trigger an arrest with or without spray-on clothing.)

There’s not a lot of public opinion data on this issue, but small-scale surveys suggest that people perceive body paint a form of clothing. In 1995, a student at Missouri Western State College showed study participants a series of nude, painted, and lingerie-clad models. The subjects made no distinction between the painted and clothed models when assessing the picture’s propriety. Five years ago, after officials at a Washington Nationals game told a shirtless man he had committed “indecent exposure,” an ESPN columnist surveyed Nationals fans about their attitudes toward scantily clad peers. While completely bare-chested men were judged acceptable by between 54 and 82 percent of the respondents, more than 90 percent felt that men who covered their otherwise bare torsos with paint should be allowed at baseball games.

Got a question about today’s news? Ask the Explainer

Explainer thanks Brett Lunceford of the University of South Alabama, author of Naked Politics: Nudity, Political Action, and the Rhetoric of the Body.