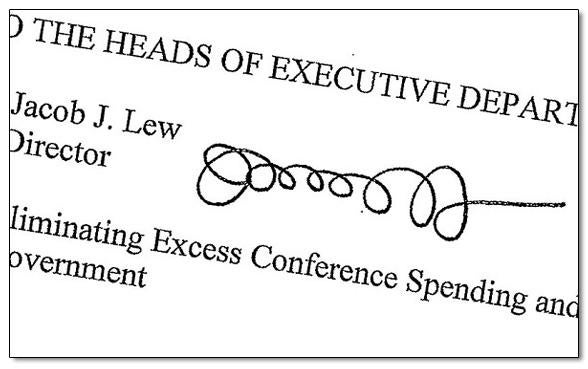

When President Obama nominated Jack Lew to serve as the new Secretary of the Treasury Thursday, he voiced a few playful reservations about his current chief of staff’s signature. The offending scribble, set to grace the dollar bill if Lew gets confirmed, is a loopy abstraction rather than a collection of letters, as if a bean bag mated with a curly fry. Said Obama: “I’d never noticed Jack’s signature, and when this was highlighted yesterday in the press I considered rescinding my offer to appoint him. Jack assured me that he is going to work to make at least one letter legible in order not to debase our currency should he be confirmed as Secretary of the Treasury.” Graphologists, who study the (pseudo) science of handwriting, have suggested that Lew’s scrawl betrays everything from a “softer approach to problem solving” to secrecy to creativity. When did we start assuming that people’s signatures revealed fundamental truths about who they were?

Since at least medieval times. The 16th century physician Paracelsus is credited for developing the “doctrine of signatures,” which held that observable characteristics of beings in the natural world could shed light on their inner essences. So a lung-shaped flower, such as a pulmonaria, was thought to have powers to treat lung disease. A mormal, or festering boil, might connote spiritual corruption, as it did for the lascivious cook in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. In 1621, after reporting a dream in which he perceived traces of God’s will in the sensual stuff of creation—in shapes, colors, sounds, and smells—a German shoemaker named Jakob Boehme wrote Signatura Rerum (The Signature of All Things). He believed that insides were legible from outsides, if we could only “read” the divine lettering inscribed into each one of God’s works. Following the same tradition, 17th century botanist William Coles claimed that the lily of the valley “cureth apoplexy by Signature; for as that disease is caused by a drooping of humours into the principal ventricles of the brain: so the flowers of this lily hanging on the plants as if they were drops, are of wonderful use herein.” Similarly, penmanship has long been thought to relate to identity in mysterious ways, even as notions of identity itself evolved from the class-based and collective to something more internal. During the 1600s, handwriting could convey important information about a person’s background, gender, and occupation. Some professions had their own prescribed fonts: The “mercantile” hand transmitted a “free and easy” character, and it was supposed to be fast and clear to help with bookkeeping. Women of high socioeconomic status were encouraged to cultivate a small, tidy “lady’s hand” for calligraphy-ing in their diaries. Some courts refused to accept legal documents that were not written in a distinct “court hand”—a grand, sweeping, authoritative scrawl with exaggerated ascenders and descenders.

Over time, as the concept of the individual with his own unique interior life emerged, pencraft began to absorb new meanings. In her book Handwriting in America: A Cultural History, Tamara Plakins Thornton investigates how our scrivening came to “embody, regulate, and generate notions of the self.” The Romantic celebration of individuality, she explains, coincided with a surge of interest in people’s idiosyncratic script. Collecting celebrity autographs became a popular 19th century pastime, one that seemed to grow out of the new fascination with genius and how exceptional men and women talked and thought and wrote. (Even Edgar Allen Poe published a series of facsimile reproductions of famous signatures.)

By the 1880s and 1890s, people were gathering John Hancocks not just from the rich and famous but from everyday acquaintances. Americans looked toward France, where the discipline of graphology was picking up popularity thanks to priest and archeologist Jean-Hippolyte Michon. At this point, handwriting analysis functioned as a kind of detective work. Its disciples used it to search out telltale clues about potential business partners, tenants, or sons-in-law, since deviant script was thought to signal an unquiet mind. (Most diagnoses occurred by analogy: Someone who left the tops of his a’s or o’s open, for instance, might invite accusations of dishonesty, since he appeared ready to drop other people’s belongings into the waiting vessels of his letters.) But they were also beginning to apply an American aspirational shine to the science: Advice columnists scrutinized readers’ penmanship samples and suggested careers to match their supposed strengths.

These days, of course, graphology slumps next to astrology and crystal healing on the shelves of pseudoscience. Multiple studies have debunked the notion that our chicken scratches have much to say about the contents of our souls. In 1988, researchers determined that writing samples held no predictive power when it came to scoring volunteers on the Myers-Briggs personality test. And a further experiment confirmed that experts in graphology could not identify the profession of 40 successful employees any better than chance. Still, handwriting experts continue to insist that the size, shape, and slant of your script, as well as the pressure with which you press down on paper, can communicate your emotional reality. (A graphologist recently said of Barack Obama’s penmanship that “its cleverly combined letters reveals a quick thinker; a consensus builder who cares about people, but who doesn’t always know when to stop building.”) Some Freudian psychologists have also wondered whether the top part of your letters contain clues about your thoughts, while the middle and bottom parts reveal your feelings and physical sensations, respectively.

One area in which handwriting analysis may have some validity is in medical diagnosis. Messy penmanship can accompany autism or other disorders that affect motor coordination. And those suffering from cardiac disease may stop and rest their pens—even for just milliseconds—more often than healthy people, which can be detected in their script by a doctor who knows what she’s looking for.

Explainer thanks Tamara Plakins Thornton of the University at Buffalo in New York.

Got a question about today’s news? Ask the Explainer.