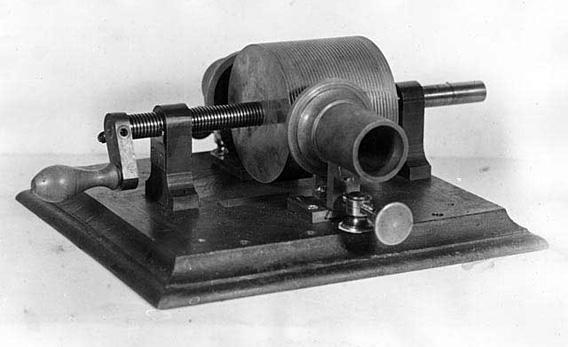

Researchers at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory have restored an 1878 recording of a political reporter reciting “Mary Had a Little Lamb” and “Old Mother Hubbard.” It is the oldest recording of an American voice. The discovery has one Explainer reader wondering: How do we know how people pronounced words before the recording age?

From spelling and personal accounts. People reveal their pronunciations in their spelling errors. A classic example is the way historians and filmmakers have tried to reconstruct the accent of Abraham Lincoln through his personal letters. Lincoln spelled inaugural as “inaugerel,” for example, suggesting that he had something of a backwoods drawl. (One imagines that, if not for his top-notch education, George W. Bush would likely spell the word nuclear as “nucular.”) In the case of major historical figures like Lincoln, contemporaries also left behind descriptions of his voice and pronunciation.

Looking deeper into history, it’s the proper spelling of the English language—rather than personal misspellings—that reveal pronunciation habits. English spelling codification began in the 15th century, and our written words are a permanent record of the way Anglophones spoke at that time. Every letter in the word knight used to be pronounced. Geoffrey Chaucer rhymed the words blood and good, because they were once pronounced “blode” and “gode.”

Migration patterns can also shed light on pronunciation habits. People in Boston and a few other Northeastern cities drop the “r” at the end of words like bar and car, because they continued to communicate with southern England after the home country dropped the sound. The Americans who migrated west and south in the 17th and 18th centuries lost close contact with the English and continued to pronounce the terminal “r.”

Quirks in pronunciation can conversely sometimes shed light on changes in spelling. The Latin alphabet lacks a letter for the English sound “th,” so early writers borrowed a runic letter called thorn, which in some representations looks like a downward-facing triangle on a stick. Thorn eventually fell out of use because it looked too much like the letter “Y.” It has stuck around, however, in phrases like, “Ye Olde Christmas Shoppe.” The first word is not meant to be pronounced “ye,” but rather, “the.”

Got a question about today’s news? Ask the Explainer.