As a writer for the Internet, I get my share of memorable correspondence. I have been the recipient of the Nietzschean misappropriations of an avowed neo-Nazi. I have been told I am “equal parts snarky and fat.” My inbox, like those of my colleagues, is a treasure trove. That said, not all emails were created equal. Take, for instance, the one I received from a college freshman I’ll call Zephyr, a student at an institution that shall remain nameless:

Hello, Mrs. SCHUMAN. An assignment for my english class requires me to write a response to your paper ‘SHOULD WE GET RID OF THE COLLEGE ESSAY?’ Funny though, my job is to refute you. So for arguments sake I was wondering if you could give you background about yourself that I could use in an essay to argue against your points. Thank you for your time.

The subject line of this letter was “Irony has a friendly face.” I’m not sure Zephyr realized quite how many levels of that device he or she had employed: effectively enlisting me to write ad hominem attacks against myself, in an essay refuting an essay against the essay—an essay, furthermore, it appeared Zephyr very much did not want to write. But I appreciated the self-awareness. (And I received Zephyr’s blessing to write about our exchange.)

The “paper” in question—which did not, incidentally, have the rather gentle title Zephyr gave it—might be the most explosive thing I have ever published, in a career that includes a piece about making obscene gestures at a baby. “The End of the College Essay: An Essay” was posted in December of 2013, when I was an adjunct at an honors college in St. Louis. (Here’s Slate’s Laura Bennett reading it aloud, with more gravitas than I have ever displayed.) At the time, I was on the business end of yet another stack of papers that my students hadn’t wanted to write. (I’m not extrapolating; they said to me, “Dr. Schuman, we do not want to write these papers.”) Watching as yet another stream of self-pitying tweets and Facebook posts from beleaguered grading professors clogged up my feed, I decided, in the spirit of contrarianism, to scorch the Earth.

Students hate writing papers, I wrote in what I now think of as “the Essay Essay,” and professors hate grading them. And because students hate writing them, most college essays are awful—and because students want nothing more than to get them over with, their writing rarely improves. So why not get rid of the thing altogether? I suggested oral exams instead, as based on a positive experience I’d had with one of my German lit courses.

But was the Essay Essay sincere? Did I—the author of hundreds of college essays, a dissertation, and an academic monograph—really believe that student essays are useless? I wanted to leave that question open, so that is why I voiced my oppositions to the persuasive essay in the form of—you guessed it—a persuasive (or at any rate vehement) essay. (Otherwise I could have just sent the Internet a text that said 📝 =🚽🚽🚽🚽).

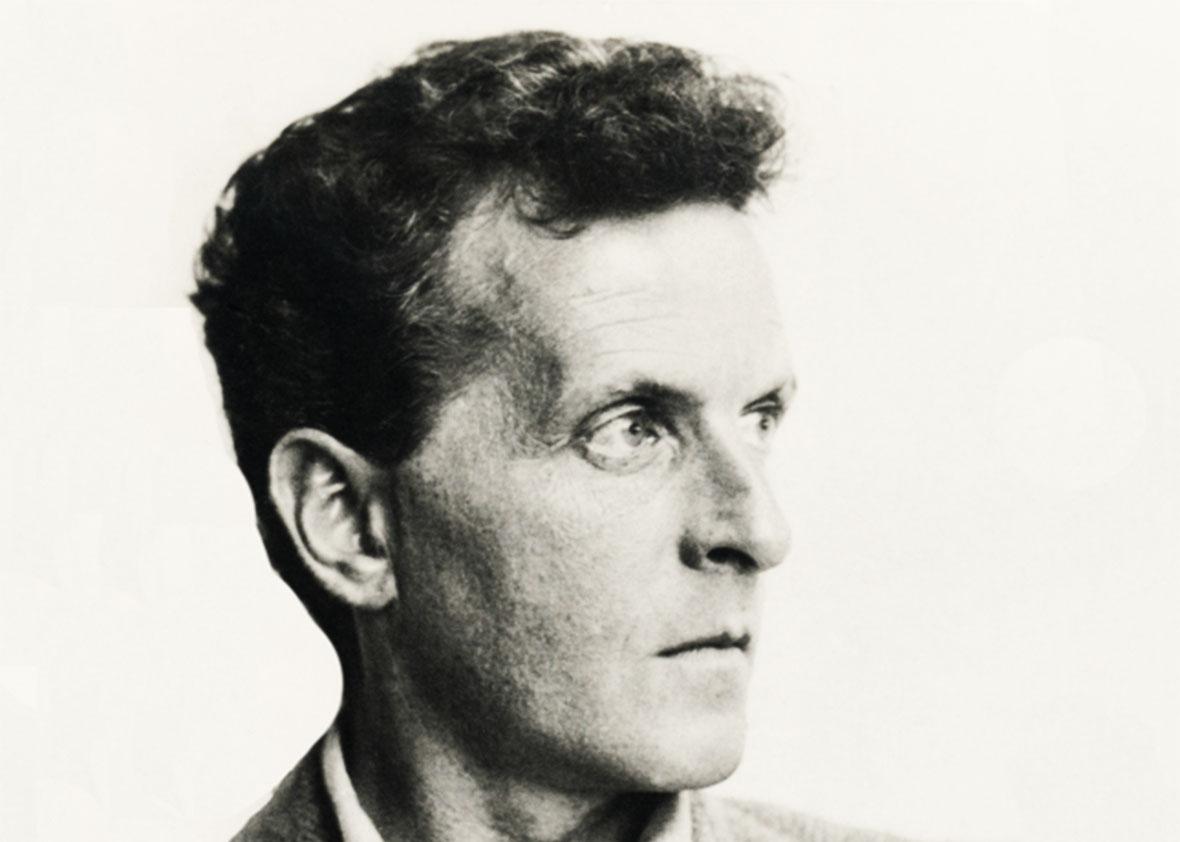

“The End of the College Essay: An Essay” was formulated in homage to Ludwig Wittgenstein, who is famous for employing a particular form to prove that very form to be unfit for its own task. (I’ve also done a PowerPoint to explain why I hate PowerPoint.) Wittgenstein’s Tractatus logico-philosophicus consists of an intricate seven-part list of declarative philosophical propositions that culminates in the declaration that declarative philosophical propositions are nonsense. The book’s final remark is simultaneously a sincere directive and by its own rules also gibberish: Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muss man schweigen. “That of which we cannot speak, we must pass over in silence.”

It turns out the entire discipline of Composition and Rhetoric—and not a few other fans of the college essay—wished I’d take Ludwig literally and STFU. The reaction was swift and vociferous, and exactly nobody found my work delightfully Wittgensteinian, although one guy did email the chair of my school’s English department demanding that I be fired. (I did not teach in the English department.) I had my first experience with a Twitter pitchfork mob. I experienced all five stages of viral-content grief: righteous indignation, hurt fee-fees, retreat, uneasy détente, and relief when something happened in the real news to knock that viral content off of Slate’s home page.

So imagine my unease to learn that not only does the Essay Essay live on, but that it’s being used in the very classroom whose discipline, composition, I offended so greatly years ago. So how to respond to Zephyr? With more irony? I elected to play it straight: “Why don’t you just write a beautiful essay? That’ll show me.”

But then I thought about it some more. Why not give Zephyr some ammunition? “Try this,” I wrote again. “Rebecca Schuman is a failed academic who advocates making obscene gestures at children. That should knock my ethos down a few pegs.” In exchange, I asked for the name of Zephyr’s institution and instructor. I wanted to see what kind of “english class” this was.

Alas, my attempts to reach out to Zephyr’s instructor proved unsuccessful, but I did manage to track down two other writing professors who assign the Essay Essay. One, William Patrick Wend, a writer and lecturer in composition at Rowan College at Burlington County, uses it as a discussion prompt. Though he doesn’t endorse my brand of vitriol, he says he does want to re-examine what college writing means. “Students are changing, the expectations of the workforce are changing, and therefore there needs to be a fluid conversation about what college-level writing is and stands for in the 21st century,” he told me. Many “had not really considered an alternative to the college essay before. I’d say 30 percent were in favor [of killing it], with many others interested but not sure what else to do in its place.” Wend, however, has thought of something: “project-based learning that still requires research, collaboration, and documentation.”

Another professor, an adjunct at a small college in the South who requested anonymity, actually assigns an Essay Essay Essay—specifically, a classic rhetorical analysis, where the students are to judge my offering on the merits of its ethos (my standing as an expert), logos (the content of my argument), and pathos (either my strongest or weakest point, depending on where you stand).

Interestingly, she tells me, even in disagreeing, a large number of her students still make many of the very mistakes I bemoan in my piece: “Since the beginning of time …” introductions; rushed arguments; yawn-y theses; spotty evidence. Unlike me, however, she has given a lot of serious thought to what causes that mediocre writing. “Students don’t recognize that they should start with questions; they want to start with answers,” she says. “As a result, they write completely obvious ‘arguments.’ ”

That’s why she sees the thoughtful summary of a scholarly argument—rather than a terrifying oral exam—as an excellent alternative to the five-paragraph structure of doom. “Perhaps they need more experience understanding the essay form before they are asked to contribute to it. If they can understand and restate an argument someone else makes, then perhaps they can enter the conversation themselves. Otherwise, we are asking them to say something—anything—about a text and they have no real reason for doing so. Hence the tendency to drown themselves (and us) in a fetid pool of generalization and fallacy.”

In the end, though, I lose on ethos, because, she says, “they couldn’t believe that anyone who hates her students’ writing so much could be an authority on teaching writing.” I will be the first to admit that that is a super-sick burn. To be fair, though, I don’t hate student writing altogether. I hate a particular kind of student writing, one trapped in a particular and cloying format, one that I find students themselves generally hate to write. And valiant Zephyr’s quest to get me to compose my own rebuttal certainly corroborated that.

So, I wonder how Zephyr’s essay ultimately went over with the prof, and if Zephyr accidentally proved any more of my points in the quest to refute them. And I also wonder, of course, how many other comp profs are out there, using the Essay Essay as a pedagogical tool and offering it an ironic redemption.

Home page photo of Rebecca Schuman by Mun Li.