So far this month in education news, a California court has decimated rigid job protections for teachers, and Oklahoma’s governor has abolished the most rigorous learning standards that state has ever had. Back and forth we go in America’s exhausting tug-of-war over schools—local versus federal control, union versus management, us versus them.

But something else is happening, too. Something that hasn’t made many headlines but has the potential to finally revolutionize education in ways these nasty feuds never will.

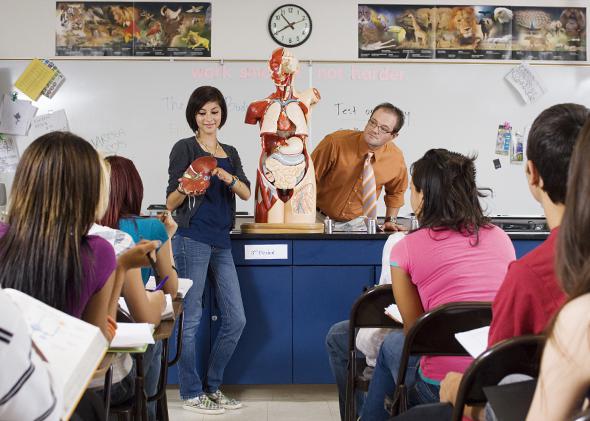

In a handful of statehouses and universities across the country, a few farsighted Americans are finally pursuing what the world’s smartest countries have found to be the most efficient education reform ever tried. They are making it harder to become a teacher. Ever so slowly, these legislators and educators are beginning to treat the preparation of teachers the way we treat the training of surgeons and pilots—rendering it dramatically more selective, practical, and rigorous. All of which could transform not only the quality of teaching in America but the way the rest of us think about school and learning.

Over the past two years, according to a report out Tuesday from the National Council on Teacher Quality, 33 states have passed meaningful new oversight laws or regulations to elevate teacher education in ways that are much harder for universities to game or ignore. The report, which ranks 836 education colleges, found that only 13 percent made its list of top-ranked programs. But “a number of programs worked hard and at lightning speed” to improve. Ohio, Tennessee, and Texas now have the most top-ranked programs. This summer, meanwhile, the Council for Accreditation of Educator Preparation is finalizing new standards, which Education Week called “leaner, more specific and more outcomes-focused than any prior set in the 60-year history of national teacher-college accreditation.”

Rhode Island, which once had one of the nation’s lowest entry-bars for teachers, is leading the way. The state has already agreed to require its education colleges to admit classes of students with a mean SAT, ACT, or GRE score in the top one-half of the national distribution by 2016. By 2020, the average score must be in the top one-third of the national range, which would put Rhode Island in line with education superpowers like Finland and Singapore.

Unlike the brawls we’ve been having over charter schools and testing, these changes go to the heart of our problem—an undertrained educator force that lacks the respect and skills it needs to do a very hard 21st-century job. (In one large survey, nearly 2 in 3 teachers reported that schools of education do not prepare teachers for the realities of the classroom.) Instead of trying to reverse engineer the teaching profession through complicated evaluations leading to divisive firings, these changes aspire to reboot it from the beginning.

To understand why this movement matters so much, it helps to talk to a future teacher who has experienced life with—and without—this reform. Sonja Stenfors, 23, is a teacher-in-training from Finland, one of the world’s most effective and fair education systems. Stenfors’ father is a physical education teacher, and she’s training to be one, too.

In Finland, Stenfors had to work very hard to get into her teacher-training program. After high school, like many aspiring teachers, she spent a year as a classroom aide to help boost her odds of getting accepted. The experience of working with 12 boys with severe behavioral problems almost did her in. “It was so hard,” she told me, “I worried I could not do it.”

By the time the year ended, she had begun the application process for the University of Turku’s elementary education program. After submitting her scores from the Finnish equivalent of the SAT, she read a dense book on education published solely for education-school applicants. Several weeks later, she took a two-hour test on what she had read. The content of the book was beside the point, Stenfors says. “I think it really measures your motivation.”

After she passed the test, Stenfors sat down for an intense in-person interview with two education professors. They described a real-world classroom scenario involving disengaged students and asked how she would respond. They probed her experience in the classroom. Stenfors went home worried, unsure how she’d done. Unlike most American students, she knew many people who had been rejected from education schools.

A month later, she got her letter. Like all of Finland’s teacher-training colleges, the university accepted only about 10 percent of applicants for elementary education in 2010, and Stenfors was one of them. “I was so happy and excited. I called everybody,” she remembers.

By accepting so few applicants, Finnish teacher colleges accomplish two goals—one practical, one spiritual: First, the policy ensures that teachers-to-be like Stenfors are more likely to have the education, experience, and drive to do their jobs well. Second (and this part matters even more), this selectivity sends a message to everyone in the country that education is important—and that teaching is damn hard to do. Instead of just repeating these claims over and over like Americans, the Finns act like they mean it.

Once received, that message has cascading benefits. If taxpayers, politicians, parents, and—especially—kids know that teaching is a master profession, they begin to trust teachers more over time. Teachers receive more autonomy in the classroom, more recognition on the street and sometimes even more pay. As one American exchange student told me about her peers in Finland, “The students were well aware of how accomplished their teachers were. I got the feeling the students saw school not as something to endure but something from which they stood to benefit.” Without those signals, teachers suffer deep cuts that go beyond salary.

This school year, after three years of studying in her Finnish university, Stenfors came to America to study abroad at the University of Missouri–Kansas City. Right away, Stenfors noticed a subtle but powerful distinction. It happened whenever she met someone new in America—in her apartment complex, at parties, wherever she went. “Every time I told them I am studying to be a teacher, people said, ‘Oh, that’s interesting.’ ” They nodded politely and moved to other, less dreary conversational territory.

“I was very proud when I said it,” Stenfors says. “But they were not so excited.” She noticed that when her friend told people she was studying business, the friend got asked follow-up questions about what she wanted to do with her degree. “I didn’t get any extra questions.”

In a blog post she wrote from Kansas City, Missouri, Stenfors reported her finding home: “Here it’s not cool to study to be a teacher,” she wrote in Finnish. “They perceive a person who is studying to be a teacher as a little dumber. … Could you imagine [being] ashamed when telling people you are studying to be a teacher?”

Stenfors felt this rebuke like a polite slap to the face. Without realizing it, she’d grown accustomed to people finding her studies impressive in Finland. There, studying to be a teacher was equivalent to studying to be a lawyer or a doctor. Even though teachers still earned less than those professionals, prestige served as its own kind of compensation—one that changed the way she thought of her work and herself.

Why did the Finns respect teachers more? Well, one reason was straightforward: Education college was hard in Finland, and it wasn’t usually very hard in America. Respect flowed accordingly. The University of Missouri–Kansas City admits two-thirds of those who apply. To enter the education program, there is no minimum SAT or ACT score. Students have to have a B average, sit for an interview, and pass an online test of basic academic skills.

Once enrolled, Stenfors’ American peers had to do just two semesters of student teaching—compared to her four semesters in Finland. They had a lot of multiple-choice quizzes (a first for Stenfors). Unlike her Finnish professors, her American instructors encouraged discussion, which Stenfors admired. But overall, the university offered less rigorous, hands-on classroom coaching from experienced teachers—the most important kind of teacher preparation.

The good news is that Finland used to be a lot like the U.S. In 1968, Finland had far more training programs for teachers than it needed. (The U.S. educates twice as many teachers as we need.) That year, Finland shut down those schools and reopened them in the eight most elite universities in the country. In time, Finland’s education schools became places where teachers conducted original research in order to graduate and spent hundreds of hours planning, practicing, teaching real students, and discussing what they had done right and wrong with veteran teachers.

Today, Finnish teachers have more freedom and time to collaborate and innovate than they did in the past—without the burden of top-down accountability policies common to low-trust systems. Parents and politicians in Finland do not pity teachers or treat them like charity cases the way so many do in the U.S. They treat them like grown-up professionals with a very hard job to do.

The lesson for America is obvious: No one gets respect by demanding it. Teachers and their colleges must earn the prestige they need by being the same kind of relentless intellectual achievers they’re asking America’s children to be.