A few years ago, the psychologist Peter Gray released a fascinating—and sobering—study: Lack of free play in millennials’ overscheduled lives is giving kids anxiety and depression in record numbers. Why? They’re missing what Gray’s generation (and mine) had: “Time to explore in all sorts of ways, and also time to become bored and figure out how to overcome boredom, time to get into trouble and find our way out of it.”

What happens when a bunch of anxious kids who don’t know how to get into trouble go to college? A recent trip back to my beloved alma mater, Vassar—combined with my interactions with students where I teach and some disappointing sleuthing—has made it apparent that much of the unstructured free play at college seems to have disappeared in favor of pre-professional anxiety, coupled with the nihilistic, homogeneous partying that exists as its natural counterbalance. The helicopter generation has gone to college, and the results might be tragic for us all.

I certainly noticed a toned-down version of this trend at Vassar, which in my day was where you went to get seriously weird (all right, not Bennington-weird or Hampshire-weird, but weird). A lot about the place was the same—interesting, inquisitive students; dedicated faculty; caring administrators—but it was also dead all weekend! The closest I saw to free play time was, I kid you not, a Quidditch game.

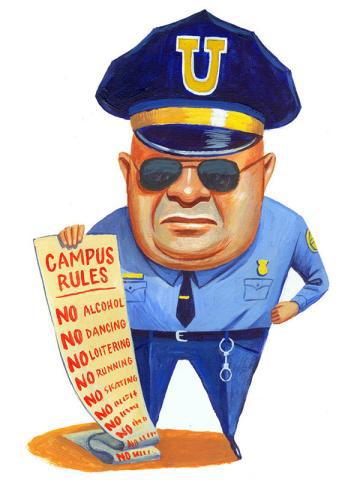

When I say the place was dead, I don’t mean there were no keggers (although there are no keggers; Vassar banned kegs in 2011—because we all know that the best way to discourage young people from doing something is to make it taboo). I mean there were just very few people out and about doing anything—because there wasn’t really anywhere for them to go. Indeed, in the past two decades, the college has done away with a lot of the minimally supervised goof off–ery that was hallmark of the extracurricular Vassar experience, including jettisoning the college pub—once the social center of campus—as well as the student-run café and dance club.

Gone, also, were the smaller moments of irreverence that contributed to my formation in surprisingly large ways: the cheeky “VASSar” shirts; the satirical back-page calendar in the school paper, the Miscellany News; the impromptu dorm parties where the “cost of admission” was a can of moss (yes, actual moss collected from a tree—which, given that Vassar is a nationally protected arboretum, was probably highly illegal).

And it’s not just Vassar. As an adjunct professor I interact more with college kids than with my peers, and I can see that my now buttoned-up alma mater is a product of its generation. An entire generation of students seems hesitant or unwilling to veer from the straight and narrow in a collegiate setting. For example, on the occasions I jettison a traditional lesson plan for something quirky (I once turned a discussion of Medea into an “episode” of Law & Order), my students’ first reaction is to wonder how the day will factor in to their “points.” It’s not their fault—it’s just our world—but today’s students spend most of their time either staring at a screen, or doing the minimum amount of work necessary to get that A that everyone “needs.”

The silly subversiveness of college—which comes from being so minimally supervised that you don’t feel compelled to spend your few free moments with a blood alcohol content of .35 percent, teetering on the precipice of an open window—is just disappearing. Even at College Confidential, where the comments of students are ostensibly free of image-scrubbing tuition-minded administrators, the best responses to their “weirdest schools” queries are Caltech, MIT, Reed, and that perpetual bastion of freak-flag eccentricity, the University of Chicago. I do not want to live in a world where the University of Chicago is considered “weird,” and nobody else should either.

Worse, any search in earnest for college “weirdness” in the national media yields articles like this, which details “Hamburger University,” a clown college, and two places where the primary extracurricular is manual labor. Yes, obviously Deep Springs College is still, and will always be, weird. But is a 4 a.m. wake-up call to milk cows and bale hay (and a strict isolation and no-sex policy!) the only way to get creative anymore?

Nowadays, unless you’re at a school where side-hugging is considered risqué, “fun” is just Greek-style partying. But partying doesn’t count as free play either—in fact, excessive drinking is just another consequence of lack of free play. It’s predictable rebellion against an overscheduled life, in the form of scheduled destruction. Since college—despite it being used more and more as career training—is actually poor career training, what it should be is life training. But without free play, it risks failing at that, too.

Someone’s got to help these damn kids today goof off more creatively, or we’re all doomed to a generation where the pinnacle of entertainment is Total Frat Move. But as temporarily palliative as, say, returning Pain and Angst Open Myke Nyte to Vassar might be, the only true generational shift will come with today’s tots. The end of college fun is not actually the colleges’ fault—if you’re a parent who overschedules your kid in the increasingly preposterous hopes that he’ll get into Stanford, it’s your fault.

Back off your damn children, and shove them outside. Strike the words “play group” from your vernacular, and give them the irreplaceable gift that Peter Gray suggests: the absence of your hovering. Not only will it help prevent them from turning into depressed, anxious mass murderers, it might also reinstill the desire for creative slacking if they do go to college, and thus give them the opportunity to be the kind of weirdos who make and run a lot of our very favorite stuff. It might make those extortionately priced four years something resembling worthwhile—or at least create Naked Vegan Croquet memories that last a lifetime.