When supper was over, the weather being hot, sherry cobblers were manufactured on a grand scale.

“Of all the liquids I know, the sherry cobbler is the most insinuating,” said Westsea.

“It is very unkind of you to say so before the ladies have taken their second glass,” said Mrs. Kelson, passing her tumbler for more ice as she spoke.

—Vaughan Morgan, Not in Society: A Posthumous Story (1868)

For much of the 1800s—roughly, from the rise of Jacksonian democracy through the sinking of the Maine—the sherry cobbler ranked as our country’s most popular beverage and the chief ambassador of her cuisine. Exported to England, the sherry cobbler—a compound of fortified wine, sugar, and fruit sipped through a straw—quenched a queenly thirst. Exhibited in France, the potion proved so delightful that it surely elicited the best French idiom expressing potational pleasure: The drink is, after all, as smooth as the baby Jesus in velvet pants. Extravagant with fine ice, it bewitched Charles Dickens on his first tour of our great nation; in American Notes, the novelist declared it a refreshment “never to be thought of afterwards, in summer, by those who would preserve contented minds.”

Today, the drink’s character still reflects America’s, I hereby posit. Hereby and also over-thereby: My recent weeks of sherry-cobbler research have inspired a minor positing spree. Why, just this past holiday weekend, I held forth that between the drink’s roles popularizing the straw and promoting the export of New England ice, it deserves a special medal of commendation from the U.S. Commerce Department. This I proposed over cobblers festooned with red and blue berries, while reflecting on the July Fourth exhilarations described by a 19th-century diarist: “ice-cream, Declaration of Independence, sherry-cobbler, military procession, national salute, fruit-cake, toasts, orator of the day, excessively wet shirt-collar …”

I had already been working on my cobbler theory for a while at this point. A couple of weeks earlier, on the evening of the solstice, I spun on the axis of my barstool and, attempting light verse and polite conversation with my seat neighbor, ventured: “Two things in America astonished Tocqueville—”

“Just two?”

“Two. He says, ‘Two things in America are astonishing: the changeableness of most human behavior and the strange stability of certain principles.’ The sherry cobbler reflects this dynamic.”

“Are you trying to posit something, mister?”

“I’m saying that the stable principle of the cobbler is that you get something delicious by mixing—perhaps in a cobbler shaker—hooch and sugar and fruit, and pouring this mix into a tall glass crammed with crushed ice.”

“And what about the changeableness? ‘Changeableness’?”

“Call it ‘mutability,’ si vous préférez. The judgment of history accepts loose constructionism of the original recipe is the correct view. You may interpret ‘sugar’ and ‘fruit’ as liberally as you like. You may muddle a lemon peel or an orange wheel, garnish with whatever berries are in season, use a half-ounce of pineapple syrup or fruit liqueur in lieu of sugar. The sherry cobbler is lovely in its pluralism.”

As if on cue, my sherry cobbler arrived, pink with muddled raspberries. My interlocutor sipped a sample. “Tastes like bubblegum,” she said.

I did not disagree. I did not disapprove. The sherry cobbler has a high risk tolerance for gaudiness. That raspberry-bright cobbler was a candied standout in the opulence of its flavor, and I have seen others so garishly garnished that they’d seem overdressed at the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. What of it? This is America, and we don’t need things that taste good to be in good taste. What is more, this is summertime, and the sherry cobbler, like the living, is easy—not too hard on the wallet, not too rough with its alcoholic wallop, just the thing for unlaxing amid 85, 95, 110 degree heat. “It is not strong to be sure,” as an Englishman observed in the 1850s, “but this is an advantage, in addition to that of the corresponding modesty of price.” Having weighed such matters and measured the beverage’s charms, I proudly present the sherry cobbler for your day-drinking consideration.

Would you like me to tell you the origin of the sherry cobbler? To chat about its name’s 1809 entry into the historical record, on the point of Washington Irving’s pen? To discuss its late 1830s ascent as “the greatest liquorary invention of the day”? To quit yapping and post a link to a good and simple recipe? Or shall I first catch us all up on its featured ingredient?

Sherry hails from southern Spain. Though currently a fashionable ingredient on the cocktail scene, it seems, on the basis of laggardly sales figures, to retain among the general public an image of fustiness and mustiness. You may feel yourself most likely to encounter it when paying a social call on a vicar or sucking up to people who might help you get tenure. (It is sensible to suppose that the sherry cobbler hit the top of the 19th-century charts because of its genteel associations. It was more ladylike than most tipples, and Prohibition historians specifically note that the moderation of the “gentleman having a cool sherry cobbler at the bar on a warm afternoon” disproved the hysterical claims of Temperance propagandists.)

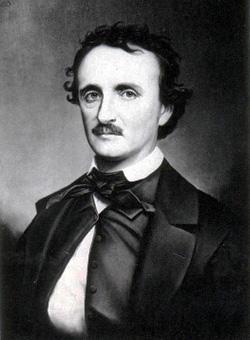

Painting courtesy of Oscar Halling/Wikimedia Commons

There are many styles of sherry. Manzanilla and Fino are on the drier side. Cream sherry and Moscatel are on your great-aunt’s sideboard. Pedro Ximénez cries out to be drizzled over designer ice cream. I have devoted the bulk of my cobbler-perfection efforts to using dry Oloroso, because its dried-fruit flavors marry beautifully with apricot and peach, and Amontillado, because I just got a big shipment in and I’m hosting a tasting party next weekend, in the damp catacombs beneath my palazzo. I’m still tinkering with the specs of a custom cocktail to be called the Edgar Allan Poire Cobbler, but roughly, it’s 3 ounces Amontillado, ½ ounce pear brandy, two dashes Peychaud’s bitters, and one dash orange bitters, garnished with an orange twist, a lemon twist, and a plot twist.

Edgar Allan Poe worked as an editor at both Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine, which described the sherry cobbler as “grateful to the delicate æsophagus,” and the Southern Literary Messenger, which heralded its recipe as “a LITERARY treat,” a claim I will second. Hold up for a second with your Hemingway daiquiris and Chandler gimlets: The sherry cobbler is assuredly the most bookish of all classic drinks, and not merely because it is excellent when sipped from a glass balanced on the splayed cover of a detective novel while lying in a hammock. Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and many other of the 19th century’s heaviest hitters addressed the beverage. It is enough to get one wondering if the sherry cobbler has special narrative properties. Mark Twain recognized the cementing of a special relationship in “the spectacle of an Englishman ordering an American sherry cobbler of his own free will.” Henry James in a memoir presents evidence of his brother William promising to “be a perfect sherry-cobbler“—an excellent balm—to their mother and aunt, and also to little Alice, “young as she may be for such treats.” Charles Dickens’ Martin Chuzzlewit depicts the sherry cobbler as a coarse nation’s silver lining: “Martin took the glass with an astonished look; applied his lips to the reed; and cast up his eyes once in ecstacy. He paused no more until the goblet was drained to the last drop.”

Photo courtesy of Wageless/Wikimedia Commons

But the great laureate of this poetic beverage is Nicholson Baker, who earns the distinction on the strength of the sixth chapter of House of Holes, 2011’s preeminent literary fuckfest. Baker nudges us into the surreality of “Cardell Has a Sherry Cobbler” very smoothly: A city planner (Cardell) asks a nice, smart, sexy lady (Jackie) out to drinks at a rooftop hotel bar, and she initiates him into the tradition. “So that’s a sherry cobbler,” he says. “Not particularly subtle—but then, who need subtle?”

Jackie sucks it up avidly, and asks, “Would you like me to tell you the history of the sherry cobbler?” Then she tells Cardell to put his hand up her dress. So far, so good. Jackie talks about crushed ice, and the popularization of the drinking straw, and she posits that Dickens’ description of Chuzzlewit’s eyes rolling back in his head “ushered in the so-called golden age of the sherry cobbler.” They have a second round and a third. He puts his hand up her dress again, and this time she lays a silver egg. Jackie—for whom I’m working on a Don’t-Even-Know-Her Cobbler (dry Oloroso, a bit of crème de cassis, and a bit of cinnamon syrup, garnished with two orange half-wheels)—then prepares to take her leave of Cardell and head to a fantasy realm: “I’m just going to the House of Holes, where I can be a total tramp for a day or two.” She says goodbye, and then, writes Baker:

“Her face began to blur and liquefy, and then she poured herself down into her straw and was gone.

Cardell picked up the straw and looked through it. There was no blockage. …

‘Your lady friend seemed to have been sucked into her straw,’ the bartender said.

‘That’s what I think, too,’ Cardell said.

The bartender shrugged. ‘It happens, man.’ ”