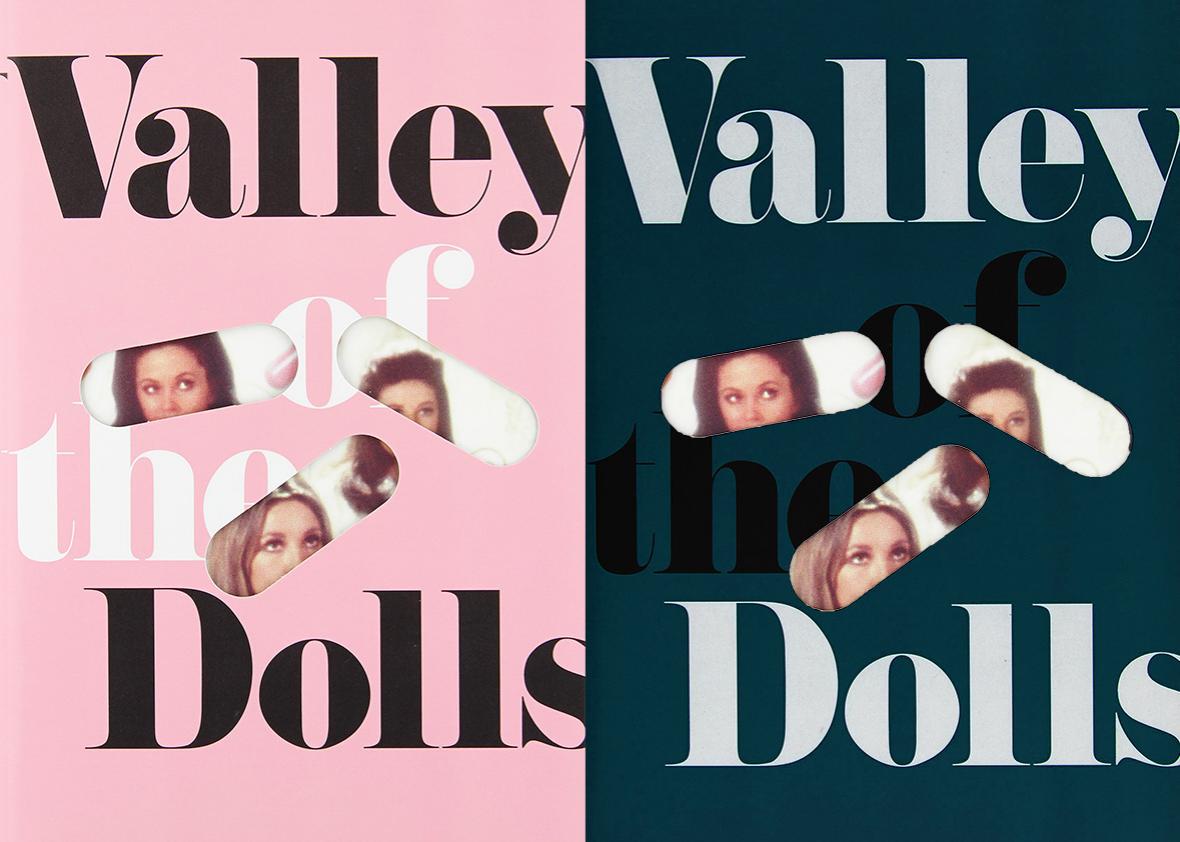

A trigger warning: This column concerns a legendary, best-selling book wherein the word fag (and variations thereof) is used a staggering 23 times. Not sounding like a lot? For comparison, the word dolls only marginally exceeds it, and it’s in the bloody title! Yes, I am talking about Jacqueline Susann’s blockbuster novel, Valley of the Dolls.

“You know how bitchy fags can be.”

“Fag!” Neely’s eyes blazed. “Don’t you dare call him that! Why, he’s – he’s wonderful. That’s all! He’s only thirty and he’s made three million dollars. And he’s not a fag!”

Slurring soubrettes, popping Champagne corks, and retina-scorching flashbulbs. Busty chicks raking in the cash, despite a glaring lack of talent. Body-conscious A-listers doing anything and everything to “lose the baby weight.” Clandestine shags, brittle egos, and lesbian trysts. Sounds like 2016, right? Baby, it was half-a-century ago.

Fifty years ago this month Susann unleashed Valley of the Dolls on an unsuspecting public. (One wonders how the public has always remained so unsuspecting, what with wicked people unleashing stuff on it morning, noon, and night.) There is no question in my mind that, 23 fag mentions notwithstanding, J.S. was five decades too early. This incredible book surely speaks more to the materialistic sexed-up mores of 2016 than to the idealistic somethin’s-blowin’-in-the-wind vibe of the 1960s. (Yes, pedants, the narrative in the book spans 1945 to 1965, but the fact remains, Valley was the best-selling fiction work of 1966, and the unsuspecting public loved it to bits.) Fame, money, power, prescription pill addictions, and boobies: The themes in Valley are just so totes now. Let’s start with those dolls:

The soft numbness began to slither through her body. Oh, God! How had she every lived without these gorgeous red dolls.

Back in 1966, pills were decidedly unhip. That same year the Rolling Stones satirized pill-popping depressed suburban housewives in their hit song “Mother’s Little Helper.” Caftan-wearing scenesters—in my mind’s eye I can see Marianne Faithfull and Anita Pallenberg lolling about on Moroccan rugs while strumming sitars—were more likely to be caught smoking hash than washing down tranks with Scotch and soda. Cut to now: Rattling pill bottles are the soundtrack to our age. Welcome to the valley of the Zannies, Rittys, Skippy, Cody, Oxy, Demmies, Dillies, Molly, Solly, Golly, and Ollie.

Another improbable theme in Valley—also much more now than then—is the extreme focus on celebrity aging:

Age settled with more grace on ordinary people, but for celebrities – women stars in particular – age became a hatchet that vandalized a work of art.

At one point Jennifer—Sharon Tate in the movie version—is put into a medically induced coma so that she can lose weight and avoid that hatchet. Like many of today’s reality “stars,” she sees her various body parts as a source of income and validation. When she learns she will have to undergo a mastectomy, she grabs the dolls and offs herself. Better to be dead than unhot, right? Jennifer’s torrid trajectory makes her one of the most contemporary characters in the whole book. At one point she even avails herself of a lesbian interlude. How 2016 is that?

And then there is all that relentless, grasping, naked ambition:

“After my next picture, I’ll be a full-fledged star. … When you’re a star in pictures you get treated like a star. … When you’re a hot-property – that’s what I am – they do everything for you. … When I have to go anywhere – like an opening – they send a car and chauffeur for me and lend me furs and dresses.”

Neely O’Hara’s rant surely speaks more to the 21st century than it did to the era of wheat germ, Dylan, and flower power. Neely—Patty Duke in the movie—is a character who seems ripped from the pages of the Daily Mail, circa now. There is a dotted line running from Judy Garland straight through Neely and thence to today and … no need to name names.

And then there’s Anne, played by Barbara Parkins in the movie. Anne is a poised East Coast girl with simple, wholesome strategic ambitions—in other words, the perfect intern. A modeling assignment with Gillian cosmetics makes her rich and catapults her into the national consciousness. By foisting maquillage on that unsuspecting public, bitch becomes a brand: Enter the Gillian Girl.

“You were a great secretary—now if you are going to be the Gillian Girl, be the best there is. Besides, what else have you got to do?” advises Anne’s agent/mentor, Henry Bellamy. Had she been working today, Anne would have become the queen of the millennials or maybe a judge on Shark Tank. You will be hugely relieved to know that not everything goes Anne’s way. She gets the guy she wants, but hubbie’s infidelity sends her lunging for the dolls. The message? Even high-functioning spokesbitches can develop a prescription pill addiction.

Helen Lawson, the old boiler with six husbands under her belt, is my I-totally-relate-to-this-crazy-lady character. A pro, a trooper, she keeps working because she is disciplined enough to actually show up and get the hell on with it. #Madonna # Fonda #Streep #Keaton #Tomlin #me

Another trigger warning: This is not the dawning of the Age of Aquarius. Valley of the Dolls is a grim fable. It’s Thomas Hardy dark. It’s Balzac bleak. It’s Dostoyevsky greige. Nothing ends well. Success corrupts. Fame destroys. Dreams become nightmares. Money corrodes. Rich men are pigs. Solid middle-class men are boring. Country life is stifling. Big cities are snake pits. Nobody is nice. Everyone is a mess. It is, in other words, the perfect mirror for today’s fame/money/free shoes culture.

And what about that movie? I have seen it multiple times and, in sharp contrast to Jacqueline Susann, I have never not enjoyed it. When the Pucci-clad authoress saw it, she told director Mark Robson that she thought it was “a piece of shit,” which sounds like something Neely might have said after one too many Nembutals.

For those of you who have not yet read the book but have seen the movie, you are in for a royal treat. Romping through the book with lurid images of Parkins, Duke, Tate, and Hayward flitting through your head is a delight. “Sparkle, Neely, sparkle”—Patty Duke’s iconic movie moment, when she bemoans the pressure to scintillate—is not in the book, but there is so much more. The characters are fully drawn, and the explosive outbursts of sizzling dialogue leave one feeling as if one has just been spanked with a feather boa.

The scene where Neely tears off Helen Lawson’s wig and flushes it down the toilet—an unforgettable, but lightening quick vignette in the movie—builds with two pages of scorching pre-flush dialogue:

Neely jumped up and stared at Helen with blazing eyes. The attendant moved closer, thrilled with this unscheduled break in the monotony …

Helen stood up and faced her squarely. “A guttersnipe. What else were you? A third-rate vaudeville tramp who never even went to school.”

Regarding the fag stuff: A year after the book came out, homosexuality was legalized in the U.K. Having emerged from the shadows, we fags, far from being insulted by either the book or the subsequent movie, were so happy to find ourselves being, at long last, unleashed with such gusto onto an unsuspecting public. And not just ourselves: Also being unleashed was our gay sensibility. Though not a gay work per se, Valley is nonetheless a tres GAY book and an insanely GAY movie. Sensibilities aside, the V. of the D. message was ultimately gay-positive and validating: So what if we’re a tad bitchy? We are everywhere. And Neely’s nelly husband has $3 million, so there!