The following piece is an excerpt from Simon Doonan’s new book The Asylum: A Collage of Couture Reminiscences … and Hysteria.

At some point in the early ‘70s, as I flicked a feather duster over wall-mounted sunburst clocks, brass carriage clocks, booming grandfather clocks and those depressing rows of moc-croc travel alarms, I was compelled to ask myself a truly heavy question: Is this how I am destined to spend the rest of my fucking life? Is this my lot?

Cuckoo! Cuckoo! Cuckoo!

After graduating college, I had returned home to Reading, Berkshire, and taken a job selling clocks and watches at the local John Lewis department store. Though I did not realize it at the time, this was the starting point of my fashion odyssey.

Working in retail during one of the most blighted economic periods in British history turned out to be a grimly surreal endeavor. In the absence of moneyed customers, or any kind of customers, I occupied myself by keeping each timepiece fully wound and synchronized. A certain satisfaction came when, upon the hour, all the carriage clocks and cuckoos ejaculated and exploded into action, scaring the shit out of the few customers within earshot.

Things looked up when I was transferred to the luggage department. Getting away from the clocks—an unwanted reminder of the horribly relentless passing of time and the inevitable approach of death—was a huge relief. And there was something undeniably upbeat about travel goods. The sight of a spanking new avocado green (remember, we are talking about the early ‘70s) Samsonite Tourister with matching cosmetics case never failed to suggest that life elsewhere was full of possibilities.

And speaking of possibilities: I also found myself working alongside a certain tall, languid queen. This attenuated person was fun and amiable, but most important, this attenuated person had a special friend named Eric. The special friend named Eric was so special that he had made his way out of our hometown and struck gold. He was working—drumroll!—as a dress designer in London.

Eric did not design dresses, per se. His specialty was “missy separates.” Missy separates were not to be sneezed at. Missy separates—tight sweaters, frilly blouses, tweedy skirts and slacks—were a huge business back then. Every young slag in Reading would somehow manage to scrape together the pennies to buy a “fab new top” or a “nifty skirt” to enhance her weekend pub crawls and nocturnal escapades.

Today, Reading is a barely recognizable gleaming beacon of reinvention. With a Premier League soccer team and masses of corporate investors such as Oracle setting up shop, Reading has never seemed more foofy and fabulous. Quel contrast! Back in my day, Reading was a slaggy, violent kind of town. On Saturday nights all the young moderns would head to the Top Rank ballroom opposite the train station, looking for pep pills and a fight. Oblivious to the peace-and-love revolution of the counterculture, and the arrival of the now famous Reading Festival, the local youth were still very much committed to mod clothes, ska music and chewing diet pills to get high.

I had one foot in this world. A pal named Jim worked at the local yob clothing store selling Crombie coats and Harrington jackets to neighborhood lads. I had my posse of straight friends. On Saturday nights we would wear our Sta-prest pants, Ben Shermans and Fred Perrys, and head to the “Rank,” where I would chat to all the girls about how great their new missy separates looked and pray to god that nobody would figure out that I was as queer as a three-pound note.

The other foot was placed in a more daring location. While working at John Lewis, I was living a double life. Every couple of weeks, I would make an excuse, throw on my Mr. Freedom polka-dot sweater—or maybe the knockoff Mr. Freedom satin jockey jacket I had stitched myself because I was so desperate to have one but did not possess the requisite dosh—and nip off to the Railway Tavern with some of my gay John Lewis pals.

These included my lifelong best friend Biddie, aka James Biddlecombe, who worked in the John Lewis soft-furnishings department. Together we made our inaugural trip to the Railway Tavern where we found the local gays. There they were, still stuck in the 1950s, squeezed into fluffy sweaters and lacey stretch nylon shirts, listening to Judy Garland, knocking back gin and tonics … and more.

Some of the gays, as Biddie and I were fascinated to discover, were locked in the vicelike grip of a strange and noteworthy addiction. They drank endless bottles of a mysterious liquid called Dr. J. Collis Browne’s Chlorodyne. Collis Browne’s was an old-school, over-the-counter “cough medicine” which had been formulated in the 19th century and just happened to contain a nice dollop of opium. We had read Coleridge at school and knew all about his opium addiction and the resulting constipation. The fact these gays were ingesting vast amounts of this antique remedy seemed very Victorian and hilarious to us.

One night we spotted a superannuated gay rummaging in the trunk of his car and stared in fascination at several crates of little brown bottles, each bearing the distinctive ye olde worlde Collis Browne label. Biddie caused a screeching furor when, later the same evening, he described his amusement at this sighting to another old queen, who, as chance would have it, was an even bigger Collis Browne’s guzzler than the first bloke. These homos hailed from the days when gays were discreet and wore green carnations. They were less than thrilled to have their secret addiction outed to all and sundry by some young Bowie wannabe. We quickly became personae non gratae.

It was hard to say which was the more frightening subspecies: the speeding, tweaking mods and soccer skinheads at the Top Rank or the highly strung, opiate-addicted poofters at the Railway Tavern. One thing was for sure: I would need to escape before somebody gay-bashed my head in or got me started on the Collis Browne’s.

Tangential though it was, the acquaintanceship with Eric, a bona fide missy separates designer, seemed to offer me a potential escape route. I was in awe of this Eric. Eric was a working-class slag who had made it out of our crap town and who was, at least from my vantage point, hitting the big time. I use the word “slag” broadly and loosely, as we did back then. I yearned to follow in slag Eric’s footsteps. I had stared at the distant glittering mirage of fashion, smoldering seductively on the horizon, for most of my short life (I was 21), and I was yearning to reach out and touch it. Eric the missy separates designer had brought me one step closer.

At this point, dear reader, I should point out that my hometown of Reading is by no means far from the fashionably madding crowds of London. It was, in fact, only half an hour by train. But, like John Travolta’s character in Saturday Night Fever staring across at Manhattan from his home in Bay Ridge, I felt that it might just as well be a million miles away. So near and yet so far.

Like a good working-class slag, Eric the missy separates designer made the train journey home once a week to see his mum. He never failed to swing by the luggage department to update his pal, the tall amiable queen, on his latest goings-on. He seemed to take a sadistic pleasure in taunting and tantalizing us with tales of the big city and all the glamorous people with whom he was now consorting. I was happy to be the object of his sadism. His stories gave me hope.

Eric told us about a wild and fascinating fellow designer whose name was Pamela something or other and who worked for—yes!—the Mr. Freedom label, my glam-rock obsession. In homage to the great record company founded by Berry Gordy, this gal had recently changed her name to Pamla Motown. To me this seemed daring, wildly camp, and outrageously glamorous. A white girl named Pamla Motown. How Afro-eccentric!

Another of Eric’s designer pals, a guy named Cliff, had a psychotic obsession with Marilyn Monroe. He had bleached his hair blond and, if Eric was to be believed, walked around the streets of London carrying a squirt bottle filled with peroxide. He used it to douse the heads of hostile construction workers and random passersby. His goal was to turn everyone he met into Marilyn, such was his commitment to the deceased movie icon. How Dada and recklessly outré!

Though clearly deranged, these two, Pamla and Cliff, had accomplished something major. They had found a place to exist, a stylish, safe, satiny, sequined space, where their insane ideas were considered an asset. I knew in my heart that crazy Cliff and Afro-eccentric Pamla were kindred misfits. The world of fashion had given them refuge. Soon it would be my turn.

I desperately needed to escape my grim town and my nutty family milieu. Fashion seemed just as nutty, but in a good way, a glam-rock way.

Twenty years later: It’s the early ‘90s. I am working at Barneys New York. I have long since exchanged my crap town for a life of fashion and fabulosity. I am not famous or ridiculously wealthy, but I am creatively fulfilled. I have found refuge in a world of rolling racks and glamour.

Though I am involved in all aspects of the Barneys store image, it is in the area of window display that I have made my name. My displays are jarring and punky and intentionally shocking: coyotes abducting babies, mannequins in coffins, fashion suicides, Christmas in July, a trailer-park tornado. My chosen themes have consistently erred toward the bizarre and unconventional. Early on in my display career I made a list of window-display taboos and then proceeded to bust them. Condoms, broken toilets, live vermin… it is hard for me to think of something inappropriate which I have not plonked in a display window at one time or another. Tammy Faye Bakker? I created an homage to her in the late ’80s. There she was, standing next to a giant mascara wand. I have even plopped a replica of Margaret Thatcher in a black leather dominatrix frock in a holiday window. I see myself as a carny, rather than an artist, presiding over my very own Coney Island sideshow. One day I got sick of making displays that were so relentlessly pristine and simply filled the window with all manner of horrible detritus, including, but not limited to, broken furniture, cigarette butts, old newspapers, shopping coupons, soda cans and half-eaten Twinkies. The perfect backdrop for precious designer clothing.

Did I lose my marbles? Negative. Window display provided me with a therapeutic outlet for all my crap-town rage and insanity. Uncle Ken and Granny had their basket weaving. I had my windows.

So there I was, working at Barneys as Head of Creative Services, which sounds dirty but is just a fancy way of saying “marketing.”

One hideously chilly winter morning an incredibly young Kate Moss entered the Barneys advertising department, wearing what looked like a monk’s habit. Her perfect bone structure peaked out from an alpaca hood. On anybody else this garb would have looked costumey, almost Canterbury Tales. On teen Kate it looked effortlessly fab.

Accompanying Kate was Corinne Day.

Corinne was the photographer who played such a key role in launching Kate’s career. She shot the now famous 1990 The Face magazine cover of Kate wearing an Indian headdress. The as-yet-unknown Kate was in New York to do her first shoot for Calvin Klein. Corinne, aided and abetted by Ronnie Newhouse and Glenn O’Brien, had just shot the Barneys spring catalog.

Corinne was from Ickenham in West London. Kate is from Croydon in South London. When they heard my accent, they asked me where I was from. When I told them I hailed from Reading in Berkshire, there was flicker of recognition from both: We had all clawed our way out of our respective crap towns and into the accepting arms of mother fashion.

We chuckled about our gritty birthplaces and joyfully compared notes. Whose town was the crappiest? I insisted on mine. After all, Oscar Wilde, who was incarcerated in Reading and wrote a bleak poem about his experience, described it as “a cemetery with lights.” From my childhood bedroom window I had a nice view of that very jail, thank you very much.

There is a kind of reverse chic about crap towns, which is hard to understand unless you were born in one. Whether we hail from Fresno or Scranton, Ickenham or Twickenham, we celebrate our gritty roots with pride while simultaneously rejoicing in the fact that we escaped.

Crap-town pride is especially pronounced among fashion folk. The chasm between the bleak naffness of that hopeless, inhospitable, rainy birthplace and the fun and magical artificiality of the fashion world is a source of delight and inspiration. Our unpretentious origins provide a knowing reference point from which to approach the ultrapretentious white-hot furnace of fashion and trendy glamour.

The list of creative slags who have fled their crap towns and dusty villages and found safe harbor in the world of fashion is a long one:

Cristóbal Balenciaga was born in Getaria, a fishing town in the Basque province of Gipuzkoa.

Michael Kors is from Merrick, Long Island.

Jean Paul Gaultier was né in Arcueil, Val-de-Marne. No, I’ve never heard of it either.

Jay McCarroll from Project Runway grew up in rural Pennsylvania.

Like the charismatic Jay, Kate and Corinne exude humor and confidence. They have that creative self-assurance which comes from being born on the naff side of the tracks but knowing that your innate sense of style and your outlier creativity were sufficiently major to propel you out of obscurity.

Despite their jeunesse and total lack of experience, Kate and Corinne had—at the time of this first encounter—just accomplished something huge. They had changed the face of fashion forever. Their collaboration created … another drumroll! … the waif.

Let’s digress a moment to chat about The Waif.

The waif was major. The waif was the biggest thing to happen to fashion since punk. But in order to fully understand the waif, we need to digress again and explain the glamazon, the tarty virago who preceded the waif.

The glamazon came along in the late ‘80s. Her look could best be described as “high drag.” Open any magazine back then and you were bound to encounter a cavalcade of maquillaged glamazons. The glamazon look was a postmodern mash-up of midcentury high-fashion dominatrix aggression. Helmut Newton and Herb Ritts and Steven Meisel all celebrated the power and stature of glamazons.

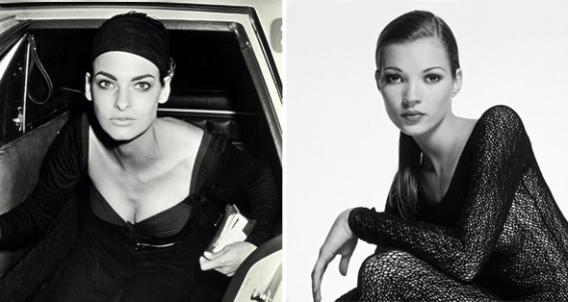

Just as with drag queens, every glamazon model’s makeup and hair was designed to pastiche the styling of a midcentury model or movie star: Linda Evangelista was Jean Patchett or Dovima or Sophia Loren or Gina Lollobrigida. Christy Turlington, in Versace with a blond skyscraper beehive and more lip liner than Lady Bunny, was Barbarella or Ursula Andress. Naomi was Josephine Baker or Mahogany. It was a cinematic postmodern explosion of hyperfemininity.

Linda Evangelista in April 1990, left, and Kate Moss in January 1993.

Photo by Ron Galella, Ltd./WireImage/Getty Images; Photo by Terry O’Neill/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Then Corinne and Kate created the waif, and David slayed Goliath.

The waif was the polar opposite of the glamazon. The glamazon shrieked with laughter. The waif barely smiled. The glamazon wore thick foundation. The waif didn’t even wear foundation garments. The glamazon was a defiant optimist. The waif was a beautiful pessimist. The glamazon was a look-at-me supervixen. Everything was externalized. The waif represented the opposite. Everything was melancholy and internal and slightly damp. The waif was the supercool working-class slag from a crap town. Corinne and Kate had stripped away the artifice of the tired old glamazon and channeled themselves. Together they obliterated the tarty glamazon and created a whole new poetic, introspective concept of style—the perfect accompaniment to the grunge movement in music—which still reverberates today.

Fifteen years later: Kate is now a household name. She has become the most famous model in the world. She has weathered various scandals and always emerged triumphant. She is still the cool girl, the chick every gal wants to emulate.

What about me? I have reached my half century, two decades of which have been spent working at the same store. I am, in some ways, the Susan Lucci of Barneys. (I refer to the longevity of my role rather than to a lack of awards. At this point I have a shelf groaning with Lucite obelisks, cut-glass rose bowls and brutalist granite blocks, all bearing my name.)

I am preparing for the arrival of Kate Moss and her Topshop clothing collection, which will make its U.S. debut at Barneys. The hip and affordable UK high-street retail phenomenon is set to conquer Manhattan with a collection designed by none other than Kate herself. Will there be any missy separates? Undoubtedly. There will be a bit of everything. Fashion after all these years has become an all-inclusive goulash of trends and styles that seem to exist concurrently: bohemian, faux-hemian, sexy secretary, manga, goth, dykey assassin, glamazon, and, yes, waif are all available for your delectation.

Along with designing the Kate Moss Topshop boutique and the opening windows, I am also charged with chatting to the press.

The New York Post calls.

In a sincere attempt to put the sheer majesty of Topshop into some kind of broader sociological context, I tell the reporter that Kate’s ineffable sense of style comes from the fact that she is “a working-class slag from a crap town, just like me.”

I go on to explain that fashion would not be fashion without the contribution made by us slags. We enliven the landscape with our refreshing lack of preconceived ideas. We neutralize the corrosive bourgeois preoccupation with luxury that can so often threaten the creativity which drives real fashion. Slag power rules!

The point I was trying to make was: All the energy and creativity in fashion comes from the crap towns like Reading and Croydon. The Sebastians and Arabellas—the toffs from Knightsbridge and Mayfair—make zero cultural contribution. It’s the lads and lasses who have fought their way out of the rough end of town who provide the creative foundations for La Mode. I cite John Galliano (a plumber’s son) and Alexander McQueen (a taxi driver’s son) as good examples. Blah! Blah Blah! I get all fired up and morph into a ranting fashion-world Camille Paglia.

The media and the blogosphere ate up my comments, or rather, I should say, a severely edited version of my comments.

The fact that my words were intended not to insult the working-class slags of the world but rather to generate a bit of crap-town solidarity was largely overlooked. Taken out of context, as they subsequently were by a billion tabloids and websites, my words sound almost menacing.

Barneys creative director disses Kate, calling her “a working-class slag from a crap town.”

They forgot the “just like me” part.

The repercussions were swift and bowel-curdling: U.K. pals e-mail me suggesting I get my bile ducts removed. Apparently the word “slag” is no longer flung around with quite the un-P.C. abandon that it was back in my John Lewis days. Not having lived in the U.K. since the ‘70s, I am, so it would appear, working with an out-of-date lexicon.

Next an admonishing call from Topshop owner Sir Philip Green. Why-did-you-call-Kate-a-slag is the gist.

This call was followed by one similar from Kate’s agent.

Then Croydon got involved.

Croydon officials used their local paper to publicly denounce my comments as “inappropriate on many levels” and reassure the world that Croydon was “a vibrant place to live with great shopping.” (This desperate attempt to rebrand their town as a red-hot tourist destination had, in my opinion, the effect of making Croydon seem, if anything, even more poignant.)

Some enterprising Brits, un-P.C. slags with great senses of humor, saw commercial opportunity in the whole debacle. They commemorated the brouhaha with a line of working-class slag T-shirts and sold them for 14 quid each on a site called duplikate.net. The T-shirts came in a bewildering variety of colors, or “colorways,” as fashion people inexplicably insist on calling them, and were accompanied by a spirited defense of yours truly.

In my own defense I would like to bring the attention of all concerned to the fact that there exists a book called Crap Towns: The 50 Worst Places to Live in the UK, which extensively highlights both my hometown and Kate’s. According to Crap Towns, making eye contact in either Reading or Croydon is always a bad idea: If you make the mistake of staring at anyone in either town, “Whatchoo lookin’ at, you fuckin’ cunt?” will be the last thing you hear before you’re poked in the eye with a half-snouted cigarette.

When Kate arrived for the opening, she was wearing a wicked little Topshop frock printed with barbed wire. Was this a portent? Hopefully not. I braced myself for a half-snouted cigarette. Instead, I am happy to report that she gave me a big hug.

Two nights later I ran into Miss Moss at the Costume Institute Gala. This is fashion’s most szhooshy occasion. No missy separates allowed.

The mesmerizingly beautiful Kate looked particularly un-Croydon. Having accessorized one of her own designs—a simple black chiffon number—with a bazillion dollars’ worth of borrowed Graff diamonds, she was easily the coolest chick in the room.

“Love the frock,” I said.

“A hundred and fifty quid,” said Kate in her best South London drawl, adding, “It’s part of me collection.”

She and her pal Irina then dive “into the lav for a quick fag.”

About 18 months ago: “You don’t mind sitting with the interns do you?”

The hostess of this particular fashion-magazine-sponsored dinner has taken the liberty of seating me at the C table. I am not offended. In fact, I am relieved. Hanging out with the newbie slags always guarantees more fun. I am delighted at the opportunity to break bread with a fresh batch of eccentric hopefuls. They are the oddballs and misfits who have, from an early age, been mesmerized by the notion of style. These are my people. Through a combo of chutzpah and creativity they have found a way in. It’s a symbiotic relationship. We brave fashion warriors bring our creative impulses and our passion for transformation. In return we get a safe space to express ourselves.

Courtesy of Blue Rider Press

So, as instructed, I take a seat and begin to chat with the gals around me. Funny, they don’t really seem like fashion daredevils. In fact, they seem rather conventional. I am used to new arrivals being a little rough around the edges. These interns are so well-spoken. With their carefully ironed hair and their perfectly applied maquillage, they seem much more like fashion consumers than fashion rebels.

In order to ascertain their names, I peek at their place cards. Those surnames sound hauntingly familiar. They are boldface last names, the names of movie stars and Fortune 500 megamoguls.

“Are you by any chance related to X?” I ask one young lass who is wearing a $4,000 Alexander McQueen outfit.

“Yes. He’s my dad.”

“And are you the daughter of Y?” I ask another gal.

“Yes. But please don’t ask me to get you an autograph.”

As I survey these lucky-sperm-club members, my heart sinks.

If the kids of the famous start nabbing all the plum creative jobs, then what about all the marginalized freaks? What about all the outsiders, the kids of the unfamous, the working-class slags from bumfuck? What are they supposed to do? Who will offer them shelter? And, most important of all, what will be the effect on fashion?

Simply put, if the idiosyncratic freaksters from the backwoods are elbowed out of the way by the kids of the famous from Knightsbridge and Brentwood, then fashion will shrivel and die.

Dear Fashion Industry,

Beware of privileging the privileged. Keep the door open to the self-invented superfreaks from the crap towns. This is the only way to keep fashion vital and creative. Thanks awfully.

Love,

SD

To read more about Simon Doonan’s years in the fashion business check out his new book The Asylum: A Collage of Couture Reminiscences …and Hysteria.