Around the turn of the 20th century—a golden age for libraries in America—the Snead Bookshelf Company of Louisville, Ky., developed a new system for large-stack library shelving. Snead’s multifloor stack systems can still be seen in many important libraries built in that era, for instance at Harvard, Columbia, the Vatican, and at Bryant Park in New York City. Besides storing old bundles of bound paper, Snead’s stacks provided load-bearing structural support to these venerable buildings. To remove the books would literally invite collapse.

A recent attempt by the New York Public Library to do away with stacks at its main branch and move much of its research collection to New Jersey invited just this concern. Engineers described the idea of removing the shelves that support the Rose Reading Room as “cutting the legs off the table while dinner is being served.” The plan was to transform the interior of the iconic 42nd Street building from its original purpose—a massive storage space for books with a few reading rooms attached—to a more open, services-oriented space with many fewer books on-site. An outcry from scholars and preservationists may yet halt the NYPL’s renovation. A revised version of the plan, which would keep more of the collection onsite, awaits a final verdict later this year.*

That decision will be just one milestone in the rapidly developing identity crisis of 21st-century libraries. In Snead’s era, a library without books was unthinkable. Now it seems almost inevitable. Like so many other time-honored institutions of intellectual and cultural life—publishing, journalism, and the university, to name a few—the library finds itself on a precipice at the dawn of a digital era. What are libraries for, if not storing and circulating books? With their hearts cut out, how can they survive?

Photo courtesy New York Public Library

The recent years of austerity have not been kind to the public library. 2012 marked the third consecutive year in which more than 40 percent of states decreased funding for libraries. In 2009, Pennsylvania, the keystone of the old Carnegie library system, came within 15 Senate votes of closing the Free Library of Philadelphia. In the United Kingdom, a much more severe austerity program shuttered 200 public libraries in 2012 alone.

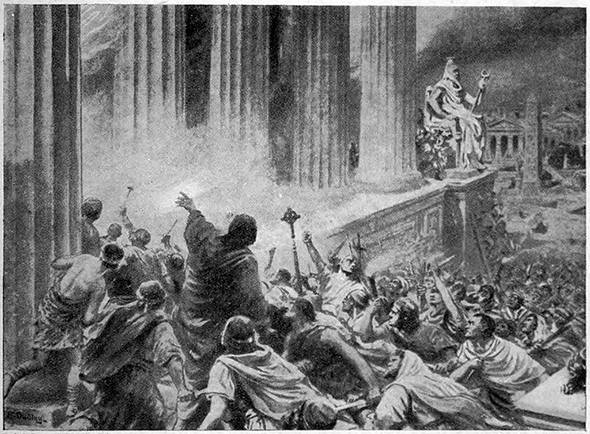

Ours is not the first era to turn its back on libraries. The Roman Empire boasted an informal system of public libraries, stretching from Spain to the Middle East, which declined and disappeared in the early medieval period. In his book Libraries: An Unquiet History, Matthew Battles calls such disasters “biblioclasms.”

The most commonly invoked image of biblioclasm is the burning of the Library of Alexandria, probably the greatest-ever collection of Hellenic manuscripts, many of which are now lost to history. In most versions of the story, the arson was committed by early Christian zealots or by invading Arabs under the banner of Islam. Indeed, either group might have seen the burning of the pagan Library as an act of devotion and a net gain for civilization. Just as likely, however, the fire is a myth that obscures a long, slow decline, and the flames that brought down the ancient library were fed not by a single man or group, but by the winds of history—changing reading habits, political instability, and the decline of the administrative state.

Will the digital age mark another era of decline for libraries? To an observer from an earlier era, unfamiliar with the screens and devices now crowding out printed books, it may look that way at first. On the other hand, even the smallest device with a Web browser now promises access to a reserve of knowledge vast and varied enough to rival that of Alexandria. If the current digital explosion throws off a few sparks, and a few vestigial elements of libraries, like their paper books and their bricks-and-mortar buildings, are consigned to flames, should we be concerned? Isn’t it a net gain?

Image courtesy Ambrose Dudley/The Stapleton Collection/The Bridgeman Art Library

Libraries have come a long way since Alexandria, of course. Much of what we’d miss if they disappeared are more recent traditions, dating back a few hundred years.

In 1888, Scottish-American industrialist Andrew Carnegie endowed a public library in Braddock, Penn., connected by an underground tunnel to a steel works he owned. As an immigrant working boy, he had been the beneficiary of an informal lending-library operated by a prominent Pittsburgher, and Carnegie wanted to pay the favor on to the next generation of strivers. Over the next decades, as he became one of the richest men on the planet, he devoted a substantial part of his fortune to building what would become the backbone of the American public library system—about 2,500 Carnegie libraries stretching from Maine to California.

Though tastes and designs have shifted, a few of the ideals enshrined in the old Carnegie libraries are still held dear today. They are monumental, carrying a reader up a flight of stairs into a beautiful building, evoking a temple of learning. The layout, with books arranged in alcoves and open shelves, encourages random browsing. Most importantly, the space is egalitarian and open to all (though Carnegie did endow so-called “separate but equal” libraries in the South). Carnegie libraries exemplify what sociologist Ray Oldenburg calls a “third place”—neither work nor home, a universally accessible space where citizens are free to congregate and fraternize without feeling like loiterers.

These ideals can still be seen in the design of many more recent libraries, even if today they’re more likely to be built in a strip mall or a converted Walmart.

Photo courtesy Christopher Rolinson/Braddock Carnegie Library/Wikimedia; ©Lara Swimmer Photography

These design benefits were ancillary, of course, to the fundamental purpose of the Carnegie libraries—access to “the precious treasures of knowledge and imagination through which youth may ascend,” in the words of the benefactor. If Carnegie were alive today, however, an Internet connection and perhaps a good e-book lending program would be enough to provide him treasures beyond his wildest dreams.

Libraries have compensated for this shift by redefining their mission around providing access to new technologies. The slow invasion of computer clusters that has defined the past two decades of library design serves an important purpose, but that mission, too, now seems increasingly redundant. Already, three-quarters of Americans access the Internet at home, with both broadband and mobile access rising steadily, particularly among younger people. It seems unlikely that providing on-site public access to online media will be a compelling justification for funding brick-and-mortar libraries even a decade from now.

Instead, librarians have begun to identify a rationale for institutional survival in the ancillary public benefits noted above, in particular the principle of a “third place” focused on learning. The British writer Caitlin Moran, mourning the closings of public libraries in her country, eloquently defends the ideal:

A library in the middle of a community is a cross between an emergency exit, a life raft and a festival. They are cathedrals of the mind; hospitals of the soul; theme parks of the imagination. On a cold, rainy island, they are the only sheltered public spaces where you are not a consumer, but a citizen, instead. … A mall—the shops—are places where your money makes the wealthy wealthier. But a library is where the wealthy’s taxes pay for you to become a little more extraordinary, instead.

Across the United States, librarians have been experimenting with ways of expanding on this newly elaborated mission—for instance, by opening so-called “maker spaces” in annexes and areas where bookshelves have been cleared out. A throwback to the mechanic’s library of the 19th century, maker spaces collect old and new technologies, from sewing machines to 3-D printers, and encourage patrons to develop and share skills that cannot be practiced over the Internet.

Photo courtesy Fayetteville Free Library FabLab

For those who might look askance at the prospect of their library morphing into a bookless social club for gearheads and gadget nerds, a group of young arts-oriented librarians have formed the Library as Incubator Project to promote a different, though by no means incompatible, vision of “third place.” On its website, the Library as Incubator Project highlights library programs from around the country that involve displaying, facilitating, or disseminating art, often by and for the local community. Favorite projects include the Local Music Project at the Iowa City Public Library, where librarians lease recordings from local artists and offer them online to cardholders for free, and the Brooklyn Art Library’s Sketchbook Project, a traveling bookmobile that accumulates donated 32-page sketchbooks from both professional and amateur artists and displays them around the country. It’s easy to imagine how a local institution built on these sorts of programs could continue to serve as hospital of the soul and theme park of the imagination long after all the paper books have been cleared away.

Photo courtesy of Oak Park Public Library/Flickr

Both maker spaces and Library as Incubator–style art programs engage library patrons to produce their own content. Also in this vein, some wealthier libraries have begun hosting self-publishing and print-on-demand technologies like the Espresso Book Machine. If basic Internet access is no longer anything to write home about, it’s notable that the cutting-edge technologies that libraries can boast of providing on-site access to are used more for creating and less for passive, traditional library activities like reading and watching.

On a broader scale, the recently-launched Digital Public Library of America, operating out of the Boston Public Library, is building a nationwide digital collection of historical materials sourced everywhere from libraries and private collections to family photo albums and boxes of old letters in the attic. According to founder Dan Cohen, the DPLA’s ambition is to work with local libraries to collect materials and perhaps eventually to present them at touch-screens designed to help patrons explore the history of their specific communities. “We love the idea of making a connection between the digital and physical realm,” Cohen says.

Here, the new emphasis on user-generated content overlaps with one of the longtime pillars of the library ideal, going back to Alexandria—a comprehensive archive of human knowledge, imagination, wisdom, and experience. The local library, the community’s traditional point of contact with that vast archive, becomes a place where we not only download culture, but upload it too.

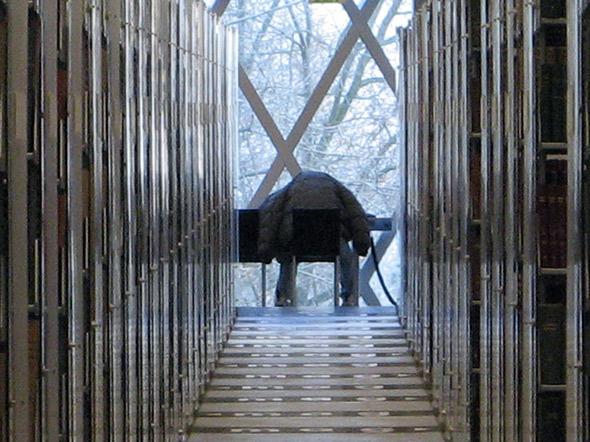

As cash-strapped public libraries scramble to reorient themselves for the digital age around access to technology and “third place” services, better-funded university libraries have been steadily pushing ahead with the same set of revamped ideals writ large. A few bold new constructions, like the James B. Hunt, Jr. Library at North Carolina State University, reflect widespread confidence that universities will always have a place for libraries as service desks, collaboration spaces, and technology access points.

The Hunt, completed in early 2013, stores the vast majority of its book collection in a compact system of metal bins accessed by book-fetching robots. Similar systems are used by companies like Walmart at distribution centers. The robots work 24 hours a day and can retrieve a book ordered from a computer or mobile device in two to five minutes. On display to the public upon entering the building, the robots have become a museum-like attraction, drawing not just curious engineering students but also children, who get a kick out of pushing a button and spurring the robots into action.

The rest of the library is an experiment in what to do with an abundance of space and a mandate for technology and collaboration. Many walls and even furniture pieces can be written on, illustrating the library’s transition away from a mood of hushed reverence. In addition to loud rooms and quiet rooms, the Hunt features several spaces that offer to the entire campus community specialized technology that might in other circumstances be available only to a certain academic program. “We find that people in other disciplines will use the technology differently, extend it,” says university librarian Susan Nutter.

Photo courtesy Jeff Goldberg/Esto

For example, the Hunt’s four visualization labs allow students and professors to share MicroTiles screens to collaborate on complicated projects that require looking at multiple images, documents, videos, or websites side-by-side. These labs attracted the attention of the campus ROTC chapter, which is training students in warship steering simulations, and the local video game industry, which has formed new research collaborations with professors on campus.

Photo courtesy Marc Hall/NC State University

The high-tech future of libraries might lie in buildings like the Hunt, but walk into a typical American public library and you’ll probably identify about three current core services: storing an underused circulating collection of paper books, ensuring community-wide access to Facebook on desktop computers, and sheltering homeless people.

As at the New York Public Library, the books are making a quiet last stand against the techno-historical forces pushing them aside. It seems unlikely they’ll hold onto their real estate for very long. The desktops are, for now, essential for a significant but shrinking slice of the population—mostly poor and elderly people—who can’t reliably access the Internet from home or on a mobile device. Eventually, the Venn diagram of those who lack smartphones and those who lack homes may nearly overlap exactly. Libraries are well positioned to serve many of the needs of this demographic, the dispossessed of the digital age.

Photo courtesy Bradleyolin/Flickr

Patching the gaps of the fraying social safety net with shelter, bathrooms, and other very basic services for people in crisis is not part of the original mission of public libraries. It can detract from other services, particularly those aimed at children. Perhaps for this reason, a library in Orange County, Calif., recently instituted a napping and odor ban.

However, public libraries have long served a progressive, interventionist agenda, putting knowledge directly into the hands of the poor, the immigrant, and those historically excluded from certain educational institutions. If no better resources can be cobbled together, isn’t it against the spirit of the library to turn away a person in need? It remains to be seen how this commitment will affect middle-class willingness to fund public libraries.

Photo courtesy Jason Eppink/Flickr

Outside of the publicly financed system, the library-as-intervention model thrives in fringy endeavors like books-to-prisons projects, the Occupy Wall Street library, or the Little Free Library’s outdoor book-sharing boxes. It’s a good time to operate one of these outsider libraries, which are particularly well positioned to make use of the vast detritus of unwanted paper books currently washing up every day at Goodwill stores and recycling centers.

It remains uncertain exactly what will happen to the New York Public Library’s Main Branch in the renovations already underway. Supposedly forthcoming is a plan that will preserve the Snead stacks as part of a new circulating library, allowing patrons to see and experience the historic stack design, which has been off-limits to visitors up until now. This plan should satisfy preservationists, if not scholars hoping to keep the research collection intact. If it carries the day, the stacks will have survived less as a functional element of city infrastructure and more as a museum curiosity for tablet-toting patrons of the future.

But perhaps it’s in the model of the museum that nostalgic and futurist visions of libraries converge. Just as families have begun to visit NC State’s campus to gawk at the book-fetching robots, so tourists of the coming decades might plan trips to 42nd Street to walk the venerable stacks that once served as intellectual aquifer to a great city in its era of cultural blossoming.

Since Alexandria, we’ve gone to libraries look backward, to give our focused, undivided attention to the wisdom and imagination of the past. This ethic, bound up for centuries in the symbol of the book, can be a kind of intervention in itself, particularly in the current era of constant distraction and multitasking. A library of the future might also be, at its best, a sanctuary where we are encouraged to spend entire hours looking at just one thing, losing awareness of our phones in our pockets, our messages that have to be checked, the thousands of informational tasks that we set for ourselves every day. The book-oriented library, where it survives in defiance of the digital shift, tends to take on the aspect of a temple for this sort of focused, old-fashioned study and contemplation.

For instance, Book Mountain, a recently completed library in the Netherlands, proudly emphasizes paper books. It abuts a 42-unit development of residential homes, the so-called “Library Quarter”—a sort of mission town for a “cathedral of the mind.”

Photo courtesy Daria Scagliola/MVRDV

These days, of course, cathedrals aren’t in much better shape than libraries. To maintain a monumental institution in the middle of a community requires patronage, in both the financial and civic engagement senses. If the people want emerging technologies more than they want books, libraries have to respond to that, even if it means closing up shop and moving entirely online.

Matthew Battles, who since publishing his history of libraries has become a principal at Harvard’s forward-looking metaLAB, believes that the future of libraries must be decided not by nostalgic scholars or librarians hoping to save their jobs, but in conversation with communities. “Librarians, scholars, policy makers all have to be part of that dialogue, but it must embrace a civic context, not the institutional context,” he says. “If you do that, having spent a lot of time in libraries and meetings with library administration, you end up in this conversation of how do you save the library. People say, ‘We know we have to change, but we don’t know how.’ There’s a death spiral in that dialogue.”

In the 1990s, the Egyptian government under Hosni Mubarak decided to rebuild the famous library of Alexandria. The Bibliotheca Alexandrina, a monumental design by the Norwegian firm Snøhetta, was completed in 2002 at a cost of about $220 million. Despite the obvious echo of the past, it is in many ways a library of the future. In partnership with the Internet Archive, it features an offline backup of every website since 1996—an early stab at long-term preservation of online materials. It is also a hub for projects digitizing early Arabic and ancient Egyptian archives.

From the start, however, the Bibliotheca has been plagued by funding problems. Its book collection has never rivaled those of other major national libraries, and, perhaps due to its Latin name, the institution has had trouble earning the trust of its own country. During the recent political upheavals, dissidents physically attacked the executive floor of the library. The director was investigated for corruption, and the library it lost its endowment. More recently, a tweeted photo of a library gift shop covered in broken glass accused demonstrators of firing bullets at the Bibliotheca and injuring security staff.

History can repeat itself. Libraries will only survive if the communities they serve want and need them to. It would be a tragedy of historic proportions if, for instance, the public library system that Carnegie endowed and inspired is dismantled in the coming decades, but it’s a real possibility. In the end, it’s up to us—scholars, makers, and artists, seekers of community, access, and safe haven, and above all, readers in the old, human sense of the word—to rise to the level of these monuments we’ve built.

Photo courtesy Ting Chen/Flickr

Correction, April 30, 2014: This article originally misstated that the original plan for the New York Public Library’s main branch proposed moving all of the research collection to New Jersey. It only proposed that much of the research collection would move to New Jersey. (Return.)

Update April 30, 2014: This article has been updated go clarify that the current New York Public Library proposal would keep more of the collection onsite than had initially been proposed.