It’s rare to coin a word or phrase that gains immediate, widespread use. So whatever you think of her shameless flackery and see-through doublespeak, congrats to Trump consigliere Kellyanne Conway. Alternative facts is the early frontrunner for 2017 Word of the Year.

After Conway uttered the Orwellian euphemism for lies on Meet the Press, alternative facts soared to the top of the language charts. A search of the news database Nexis showed 283 mentions of alternative facts on the day of the show, Sunday, Jan. 22—and more than 5,500 since. Google News hits have topped 1.2 million. Does that mean alternative facts will wear the Word of the Year crown? Well, 2017 is young, language moves fast, there’s a lot of political and cultural ferment to come; another promising early candidate, kompromat, already may have peaked. But I bet alternative facts does win Word of the Year—if only because there are so many Words of the Year these days.

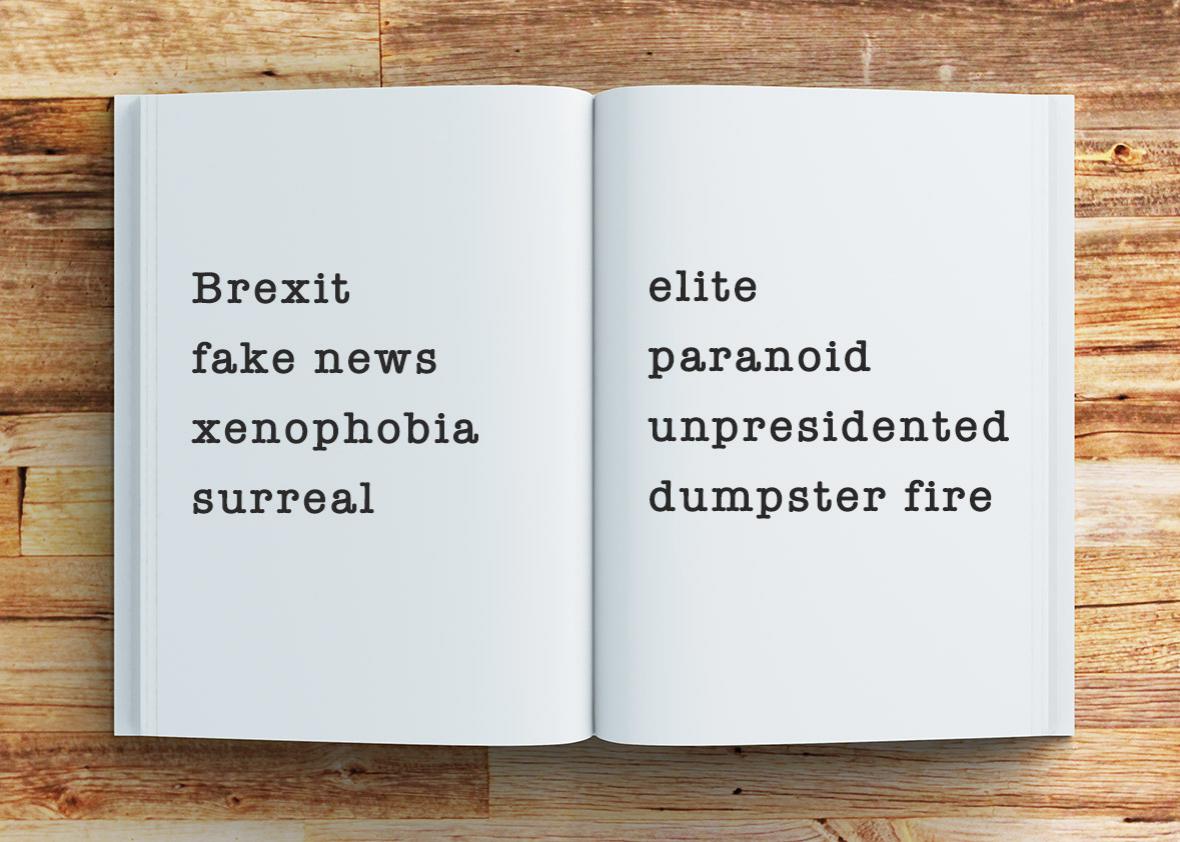

Started in 1990 by a small group of linguists, Word of the Year has spread like a video of an anarchist punching a Nazi that’s been set to music. WOTY 2016 season began way back on Nov. 3, when the English publisher Collins picked Brexit. It didn’t end until last week, when the Australian publisher Macquarie announced its choice, fake news. In between came post-truth (Oxford), xenophobia (Dictionary.com), elite (Macmillan), surreal (Merriam-Webster), and paranoid (Cambridge). On Slate, etymologist John Kelly selected 2016. The Guardian chose the Trump Twitter malaprop unpresidented. Members of the American Dialect Society voted for dumpster fire. The Australian National Dictionary Centre picked democracy sausage, which beat out census fail, smashed avo, shoey, and other Aussie-isms.

The blog Strong Language handed out dirty-words awards (creative uses of fuck abounded). On Slate’s Hang Up and Listen, my fellow panelists and I crowned a Sports Word of the Year (the concussion-related phrase in the protocol, bypassing the Trump excuse locker-room talk). Foreign languages WOTY-ed, too. The Society for the German Language went with the self-explanatory Postfaktisch. Norway’s word was hverdagsintegrering, “the everyday efforts of ordinary residents to integrate refugees and immigrants into society.” Austria’s 52-letter winner, Bundespraesidentenstichwahlwiederholungsverschiebung, looks like it’s trolling the very idea of Word of the Year.

That’s more than a dozen WOTYs right there. For dictionary publishers, WOTY isn’t a purely academic matter. While small staffs perform the nitty-gritty work of defining new words and updating existing entries, behind the scenes, publishers like Merriam-Webster, Oxford, and Dictionary.com are writing computer code and creating editorial content to drive their products to the top of Google’s search pages and attract more eyeballs for advertisers. In the battle for online users, WOTY is an important seasonal front.

The first Word of the Year (in English, that is; the Germans have been doing it since 1971) was chosen by the American Dialect Society in 1990. Founded a century earlier, the group of academics and lay word people had been tracking new words in its journal, American Speech. But those efforts didn’t get much attention. At its annual meeting in Chicago, the society decided to select a Word of the Year and send the results to the media. “I was thinking that Time magazine has its Person of the Year and why can’t we do for words what Time did for people?” says Allan Metcalf, an English professor at MacMurray College in Jacksonville, Illinois, and the society’s executive secretary. The 30 or so attendees chose bushlips, a portmanteau word meaning “insincere political rhetoric,” referring to President George H.W. Bush’s broken campaign promise, “Read my lips: no new taxes.” The losers included politically correct and bungee jumping. Linguists aren’t necessarily good prognosticators.

Times have changed since that first gathering. Last month, more than 300 people packed a hotel ballroom in Austin, Texas, to pick the American Dialect Society’s 2016 champ. There were impassioned speeches for and against nominees (“I hate to promote these metaphors that use violence,” someone said of slay. “Lots of people have been slain recently.”). There was linguist lingo (“dysphemisms,” “combining morphemes,” “definiens”). There were Trump jokes (“I’m in favor of tiny hands because I would like to see Donald J. Trump tweet at us.”). Fingers were snapped in approval. Votes were registered by a show of hands. Dumpster fire, in lexical and emoji form, defeated woke in a runoff. (Disclosure: I’m a dues-paying member of the American Dialect Society. I nominated tweetstorm for Digital Word of the Year. It lost, alas, to the verb use of the @ symbol on Twitter, as in “Don’t @ me.”)

Dumpster fire’s victory generated a burst of hashtagged chatter and a handful of articles based on a news release written by the society’s New Words Committee chair, Ben Zimmer, language columnist for the Wall Street Journal. Zimmer and a few other linguists wrote their own pieces or talked on radio shows and podcasts. Zimmer says the amount of coverage was about average, but in previous years the New York Times, Time, and Washington Post sent reporters. “It’s certainly a different landscape than when the American Dialect Society’s choice was the only game in town,” Zimmer says. “It gets less attention.”

Unlike the playful free-for-all at the dialect society gathering, leading dictionary publishers take an empirical approach to WOTY. That’s partly to set themselves apart, and partly because the digital tools used by modern lexicographers are WOTY-friendly. Merriam-Webster, for instance, bases its choice on online word lookups and newsworthiness. Surreal won last year, Merriam said, because “it was looked up significantly more frequently by users in 2016 than it was in previous years, and because there were multiple occasions on which this word was the one clearly driving people to their dictionary.”

Merriam editor-at-large Peter Sokolowski says total lookups for surreal increased by about 80 percent last year as compared to 2015. Three big monthly news-related spikes boosted its WOTY-worthiness: in March, after the Brussels terror attacks; in July, after a coup attempt in Turkey and a terror attack in France, and during the Republican National Convention; and in November, after you know what. Other events triggered smaller bumps: the death of Garry Shandling; Donald Trump’s vice presidential announcement; golfer Danny Willett’s victory in the Masters; news stories about President George W. Bush’s handwritten notes from Sept. 11, 2001; Meet the Press host Chuck Todd’s description of a presidential debate; the shooting of police officers in Dallas; and a comment by NBA player Dwyane Wade after he left the Miami Heat for the Chicago Bulls. “It was also used in its original sense in reviews of The Lobster,” Sokolowski says.

Merriam put its Collegiate dictionary online in 1996 for free. “As soon as we started seeing the site logs, it was so clear,” says John Morse, who recently retired as Merriam’s president and publisher. People were looking up tricky words like affect and effect. But there also were bursts of lookups after big events: for paparazzi and cortege after the death of Princess Diana in 1997; impeach during the Monica Lewinsky scandal in 1998; rubble, triage, terrorism, and yes, surreal after 9/11. Merriam named its first WOTY in 2003, democracy, which surged after the invasion of Iraq by U.S. forces. The conclusion: People were less interested in looking up new slang or high-tech terms than in knottier words that popped up in the news.

Facing WOTY competition, Merriam twice let users pick a winner (truthiness in 2006; w00t in 2007). But that didn’t move the marketing needle, Morse says, so the company returned to its empirical approach, which is now central to its business strategy. Merriam’s irreverent Twitter feed and its website posts feature words whose online lookup numbers are “spiking.” The strategy, Morse notes, is consumer-directed. Words entered into a dictionary reflect what professional lexicographers decide is linguistically important; Merriam’s WOTY reflects what readers decide is linguistically important. “The word [that users] looked up the most last year is more interesting than a bunch of lexicographers staring into their navels and saying alt-right,” Morse says.

Merriam isn’t alone in pushing a data-based WOTY. Dictionary.com said lookups for its victor, xenophobia, spiked 938 percent the day after the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union, with “hundreds of users looking up the term each hour.” The website’s WOTY post was supplemented with charts and an impassioned talk by former Labor Secretary Robert B. Reich. Oxford Dictionaries, meanwhile, said its WOTY choice—post-truth—was based in part on a spike in the “frequency of word use” in written text.

Katherine Connor Martin, Oxford’s head of U.S. dictionaries, says Oxford employs several proprietary corpora, or collections of text, to identify words and analyze how and how often they are used. One of them, a “tracking corpus,” gathers and time-stamps internet content, which editors can examine for month-to-month trends. To pick its WOTY, Martin says, Oxford editors assembled a list of more than 100 lexical terms and assigned finalists a “2016-iness score” based on the data and their opinions. Post-truth surged in the Oxford tracking corpus starting in May. And it had the new-word sex appeal that makes a good WOTY.

There is one WOTY holdout. Instead of joining the word-picking party, the American Heritage Dictionary compiles a one-page media handout with a sampling of terms added to the dictionary that year. The 2016 list, featuring words like glamping and microbead, was decidedly nonpolitical. Steve Kleinedler, the dictionary’s executive editor, says skipping WOTY separates American Heritage from the pack and lets it target a few substantive media appearances. “I remember Dictionary.com’s word, xenophobia, but I’ve completely forgotten what Oxford and MW chose already,” Kleinedler says, “so I really like our approach.”

WOTY may be about marketing and competition—Merriam boasted that its surreal announcement generated more than 9 billion “press impressions.” And WOTY fatigue is certainly real. But the higher purpose remains worthwhile: to connect language and culture and parse the zeitgeist of the annum gone by. The crowded WOTY field helps accomplish that even more effectively. Because 2016 was a surreal, xenophobic, Postfaktisch dumpster fire. And 2017 isn’t offering any alternative.