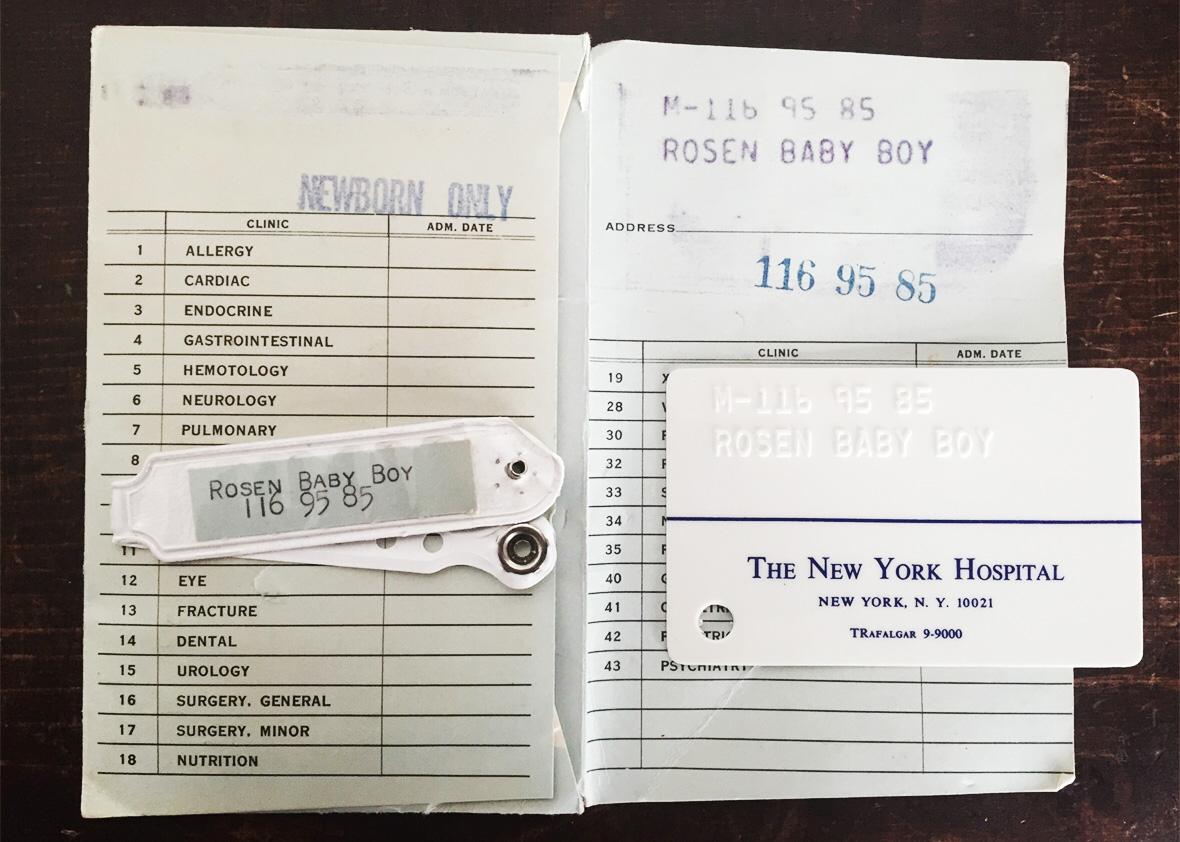

I was born at 8:15 p.m. on June 21, 1969, in New York City—as good a setting as any for a Jewish farce. I’m told that my mother and father took a few days to decide on a name for their child, and I have evidence to prove it: a tiny New York Hospital bracelet, with a type-written tab identifying its wearer as “Rosen Baby Boy.” Once, my parents might have stopped there. According to the Social Security Administration, “Babe” cracked the list of the Top 1,000 most popular names for American male newborns in the year 1899. But the 19th century turned to the 20th; soon, Babe went the way of Bud, Mose, Enoch, and other names redolent of ragtime and flannel baseball uniforms. By the time my parents bundled their baby into a taxi for a ride across the Brooklyn Bridge to a second-story floor-through in Carroll Gardens, I was Joel Harold Rosen.

Jody Rosen

My mother chose the name Joel after the biblical prophet. (She was fond of the famous lines in Joel 2:28: “Then afterwards, I will pour out my spirit on all flesh; your sons and daughters shall prophesy; your old men shall dream dreams and your young men shall see visions.”) I was called Harold in deference to the Jewish tradition of naming a child for a deceased relative: My paternal grandfather, Harold Rosen, had died several years earlier.

All in all, it was a reasonable name for a baby boy. But as Benjamin Franklin observed, Force shites upon Reason’s back, a law that applied in Brooklyn bourgeois bohemia in 1969, where the Force of counterculture was strong—strong enough to compel a young couple to seek a nickname with a certain left-of-center flair. My parents are fuzzy on the details, but a few weeks after my birth it was decided that the name Joel was “too adult” for an infant. They began calling me by the name that has stuck with me since, the name that appeared on my nursery school attendance roll, that was inked in permanent marker on my schoolboy’s knapsack, the name on my college transcript, my passport, my driver’s license, and the byline of everything I’ve published: Jody.

It’s a curious name with an obscure history. Naming dictionaries list more than a dozen spellings and variations: Jody, Jodi, Jodie, Jodee, Jodey, Joedee, Joedey, Joedi, Joedie, Joedey, Jodea, Jodiha, Johdea, Johdee, Johdi, Johdey, Jowde, Jowdey, Jowdi, Jowdie. Its origins are Hebrew. Jody is a diminutive of Judith, which means, simply, “woman of Judea” or “Jewish woman.”

Our given names are time stamps, products not just of deep religious and cultural traditions, not just of the whimsies and agendas of the individual name-bestowers, but of that vague force that we call the zeitgeist, the prevailing winds of fashion and fancy, which, consciously or not, guide our writing hands as we fill out birth certificate forms. In A Matter of Taste: How Names, Fashions, and Culture Change, an influential study published in 2000, Harvard professor Stanley Lieberson brought social scientific scrutiny to the puzzle of American baby-naming practices. Among other insights, Lieberson ascribed the popularity of certain names to fluctuating subfads for “name sounds”—the J name beginning, the n or ee endings, the hard k inside of the name, etc. Lieberson also concluded, contra conventional wisdom, that naming trends have a tendency to arise simultaneously across boundaries of race, ethnicity, class, and region. A name that strikes the perfect notes of novelty and nonconformity for a mom and dad in Manhattan might well hold the same appeal, at the same moment, for parents in Manhattan, Montana.

My own name would seem to be a case in point. If you examine the Social Security statistics, you find that, in the year of my birth, Jody placed 175th on the list of male baby names, its second-highest ranking in the century-plus that the numbers have been tracked. (It placed slightly higher, in 162nd place, two years later.) Like the moonshot and Woodstock, Jody is a period piece: just so 1969. More than any era before or since, this was the time when a Jewish boy, circumcised in accordance with the ancient covenant, could be born a woman of Judea.

Jody may have been a trendy name, but the trend was short-lived, and it didn’t meaningfully alter the big picture. One of my earliest memories is of some other kid’s mother peering down at me in a sprinkler park and instructing: “Jody is a girl’s name.” This wasn’t the nicest thing to say to a child, but the lady wasn’t wrong on the facts. Historically, the name Jody has been given to females far more frequently than males. And forget history: On the playgrounds of my boyhood, popular culture held sway, and according to pop culture, Jody was not just a girl, but worse, a country girl, and worse still, a country girl doll.

Jody Rosen

Jody the Country Girl Doll was manufactured by Ideal, then the largest doll company in the United States. Ideal’s Jody belonged to that cultural moment when post-Watergate malaise and post-hippie back-to-the-land idealism combined to flood American culture with pastoral nostalgia—the period that gave us such artifacts as the Little House on the Prairie television series, the hit “nature movie” The Adventures of the Wilderness Family (1975), and John Denver quavering “You fill up my senses/ Like a night in a forest.” Jody looked like a Barbie doll, but her hair was brown and her clothes were those of a prim 19th-century frontierswoman. The doll had a long orange-brown skirt and a print blouse with lace trim; she wore billowing bloomers, and her hair stretched to her ankles. You could also purchase a variety of Jody the Country Girl Doll play sets: Jody’s Farmhouse, Jody’s Country Kitchen, Jody’s Victorian Parlor. It was a quaint vision that held special appeal in the New York of my childhood—the graffiti-bombed, stagflation-beset mid-’70s necropolis—and the doll was advertised incessantly during the cartoon broadcasts that aired mornings and afternoons on channels 9 and 11. These ads featured a jingle, which every kid in the city seemed to know. The song followed me around on schoolyards and jungle gyms, delivered by my playmates in taunting singsong:

Jody, oh Jody—she’s the country girl doll

Sweet pretty Jody—the country girl doll

Pretty face, pretty dress, and pantaloons too

And long pretty hair reaching down to her shoe

Jody, oh Jody—she’s the country girl doll

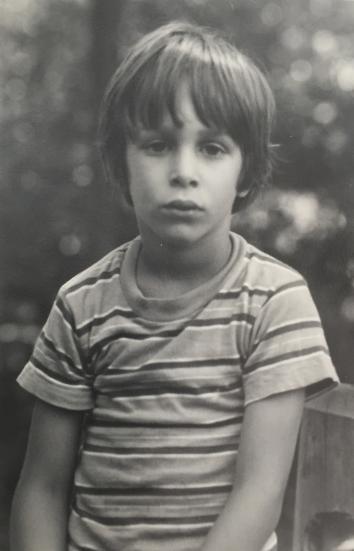

My parents had split up shortly after my first birthday. By the time I was 3, my mother and I had moved to Morningside Heights in Manhattan, near Columbia University. Not long after, my mom came out as a lesbian, and her girlfriend, Roberta, moved into our apartment on West 121st Street. It was an unconventional family arrangement, but I can’t claim that it was “difficult” or traumatic. On the contrary: I was a happy kid. Still, in the 1970s, even in the progressive bastion of the Upper West Side—where the hallways of Classic Sixes were hung with African masks, and Free to Be… You and Me blared from Fisher-Price turntables in well-appointed children’s bedrooms—a lesbian mother was something that you hid. As I reached adolescence, the sense that I was bearing a shameful secret, compounded by the usual male sexual anxieties, heightened in turn by the rather matriarchal atmosphere of my upbringing and the nagging psychic itch of my girly boy’s name—all this left me with a feeling of vague existential ill-ease that I couldn’t quite shrug off. My mother once mentioned that had I been born a girl she would have called me “Tanya.” In my darker moments, I suppose I must have wondered if she called me Jody because, secretly, she longed for a Tanya.

As it turned out, I met a Tanya at a party my freshman year of college. She wasn’t beautiful, but she was alluring, with a head of jet-black hair that had been hacked into a jagged punk-rock pixie cut, and a brain that moved faster than mine. In short, she was out of my league. Trying to make small talk, I told her that I had almost been Tanya myself. “You’re lucky you’re not,” she drawled, fixing me with a glare. “All girls named Tanya are sluts.” It was a slow underhand pitch—but I was 18 and could only wave my bat at it feebly. I don’t remember any of the conversation after that. When I try to picture the scene, I see my mouth opening and closing like a ventriloquist’s dummy’s, with no sound coming out, until Tanya drifts off in the direction of a fellow with a square jaw and a rock-solid name to match: Brad or Chad or Rod.

But was Tanya right: Is a person’s name her destiny? The most famous argument to the contrary is Shakespeare’s: “What’s in a name? that which we call a rose/ By any other name would smell as sweet.” But Judaism takes a different view. Rabbinic tradition holds that names have the power to shape their bearers’ souls and fates. One esoteric belief, derived from a passage in the Talmudic tractate Rosh Hashanah, proposes that death from a serious illness may be averted by an eleventh-hour name change. Then there’s Exodus 3:13–14, the burning bush scene, where God, asked His name by Moses, offers a cryptic reply, variously translated as “I Am Who I Am,” “I Am That I Am,” and “I-Will-Be-Who-I-Will-Be.” The theological and philological mysteries of these lines have been probed for thousands of years over thousands of pages, but we might add the simple observation that God is name-wary: He knows that a name is a burden and doesn’t wish to be pinned down on the topic. As Marshall McLuhan put it: “The name of a man is a numbing blow from which he never recovers.”

Certainly, angst about names runs high, and belief in their talismanic power is pervasive, across cultures and around the world. In 2012, the Wall Street Journal reported on a booming name-change business in Thailand, where there is widespread conviction that the wrong name can confer bad luck and that a new one may reverse the trend. The most sensible approach might be that of Native American tribes like the Lakota, who hold that an individual’s name can change throughout his or her life, with fresh names given to mark new circumstances, experiences, and accomplishments.

Today in the U.S., anxieties about names are addressed—or more accurately, inflamed—by a multimillion-dollar baby-naming industry, encompassing paid consultants, websites, and a vast popular and pseudoscientific literature. (Recently, I clambered my way through the charts, graphs, and astrological musings in Norma J. Watts’ The Art of Baby Nameology, “a study of names based on the Pythagorean Method of numerology.” Watts’ formulas were abstruse, but I was able to determine that the name Jody boasts a “power number” of 9, which correlates to a philosophical disposition and a personality with “a tendency to drift.”) Americans in 2016 find themselves in a vast marketplace of baby names, largely loosed from the religious, clan, and caste strictures that once guided naming customs. Meanwhile, the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment and the Due Process Clause of the 14th ensure that the laws restricting what parents may name their children are more permissive here than practically anywhere on earth. The exceptions tend to be quirky state laws, like the one in Massachusetts limiting the length of given names to fewer than 40 characters, for reasons related to computer imputing.

Jody Rosen

This freedom to call our kids what we want to is, of course, as American as apple pie; undoubtedly, a child named Apple Pie will be born this week, probably at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. Still, I can’t help preferring the stodgier approach of our cousins overseas, where governments have more latitude to intervene—to protect children from names that might expose them to ridicule and hardship. Who can deny the wisdom of the French judge who said non to the name Nutella, or the Danish authorities who intervened to prevent lunatics from christening their newborns Anus?

Of course, Americans have strong feelings about bad baby names. We tut-tut the silly names celebrities choose for their offspring. And we have a body of uniquely American fables about poorly chosen names, including cautionary tales highlighting the special stigma of gender-inappropriate names. The most indelible is the rollicking Shel Silverstein song popularized by Johnny Cash, “A Boy Named Sue,” the tale of a vengeful son who vows to “search the honky-tonks and bars and kill that man who gave me that awful name.”

For the record, I never wanted to murder my parents. When I was a child, my mother would remind me that, technically speaking, I was Joel Rosen; I could use that name at any time. I recall her once promising that she would support me in legally changing my name to a new one of my choosing. I doubt that this offer was serious, but I thought it was at the time, and I spent long hours contemplating alternative names. For reasons that are inexplicable to me now, my favorite candidate—the name that seemed to my 8-year-old mind to capture my hidden essence—was “Colin.”

Yet neither Colin nor Joel nor any other name would do. I was Jody Rosen; I’d never been anything but. The name rankled, but the idea of using some other one seemed preposterous, unimaginable—I could no more change my name than I could unscrew my head from my neck.

So I coped. I comforted myself with the knowledge that I was not alone, compiling a pantheon of male Jodys. The pickings were slim. There was Jody, the redheaded twerp on the ’60s sitcom Family Affair. There was Jody Davis, a catcher for the Chicago Cubs who placed 10th in the National League Most Valuable Player voting in 1984. There was guitarist Jody Williams, renowned for his raucous soloing on Bo Diddley’s “Who Do You Love?”

I didn’t know it then, but there was another Jody out there—an even more vigorously virile Jody than President Carter’s press secretary, Jody Powell. In the summer of 1996, I hailed a taxi outside the PATH commuter rail station in Hoboken, New Jersey. I struck up a conversation with the cabbie, who asked me my name.

“Jody?” he said. “You’re a pimp.”

I laughed. “Uh, no, not really.”

“No, no, no—if your name is Jody, you’re a pimp.” The driver looked me over in the rearview mirror. “I can tell, you’ve got some Jody-ness in you.”

The driver was a U.S. Army veteran, who had served in Vietnam. He explained that military cadences, the call-and-response songs chanted by soldiers while marching and running, are known as Jody calls, or, simply, Jodies, a name derived from the stock character who plays a starring role in many of the cadences. As folklorist George G. Carey has written: “Jody is that mythical figure who stays at home and, after the soldier has been inducted, steals his girl, his liquor, and runs off with his clothes and his Cadillac.” (My taxi driver was blunter: “Jody is the motherfucker who’s fucking your woman while you’re in the service.”) A famous U.S. Army cadence distills the Jody legend in a few rhymed couplets:

Jody this and Jody that

Jody is a real cool cat

Ain’t no use in calling home

Jody’s on your telephone

Ain’t no use in going home

Jody’s got your girl and gone

Ain’t no use in feeling blue

Jody’s got your sister too

Some cadences dwell on the obscene particulars of Jody’s adventures. Some take the form of revenge fantasies. (“Back home Jody’s got my wife/ Gonna take a Chap and end his life.”) Others, like the Vietnam-era Marine Corps cadence “Hey That Jody Boy,” give voice to class resentments: “Well, Jody’s got your girl/ And Jody thinks he’s cool/ ’Cause Jody’s back in school.”

The Jody calls serve a dual purpose, providing a martial rhythm to keep soldiers in formation while expressing the fears of enlisted men and the animus they harbor toward civilians. Today’s servicemen have elaborated and updated the Jody tradition. One example is a vehement acoustic guitar ballad uploaded to YouTube by a Marine in 2007, at the time of the Iraq war troop surge. The song imagines Jody’s bedding of a soldier’s spouse in lurid detail (“Jody’s gettin’ off,” goes the refrain), before concluding that military men are justified in having extramarital sex during their deployments. Elsewhere on YouTube you will find “Jody Got Your Girl” (2010), a hip-hop–style cadence performed by four Fort Lee, Virginia–based Army recruits. The video, the men make clear, is a kind of public service announcement, a friendly admonition to fellow enlistees. “If you ain’t met Jody, you’ll find him,” they explain. “He out there. He lurking.”

He’s been lurking for quite some time. The Jody figure has a history predating its World War II–era absorption into military culture, a lineage that stretches into the primordial American past. Jody began his life as Joe the Grinder—or Joe de Grinder, later contracted to Jody—a priapic fixture of Southern black oral culture. He surfaces, for instance, in a ghostly field holler, “Joe de Grinder,” performed by Irvin “Gar Mouth” Lowry in a 1936 recording made in Gould, Arkansas. An even more evocative document is a Texas prison logging gang’s work chant, captured by a film crew in the mid-1960s, though the song itself is of far older provenance. “Jody,” a swaying call-and-response punctuated by the inmates’ rhythmic ax falls, weaves together laments about backbreaking labor (“I’ve been working all day long/ Pickin’ this stuff called cotton and corn”) and the hardships of imprisonment (“Six long years I’ve been in the pen”) with lines about Jody’s cuckolding conquests: “Ain’t no need of you writin’ home/ Jody’s got your girl and gone.”

Jody/Joe the Grinder has continued to slink through the backstreets of American culture, popping up in scores, possibly hundreds, of poetic “toasts,” doo-wop rave-ups, blues plaints, and soul, R&B, and funk songs. All of these offer variations on the classic Jody narrative: A man in a situation of confinement—in the military, in prison, working all night on a graveyard-shift job—is preyed upon by Jody, the wily sexual scavenger. As scholars have noted, the Jody narratives register the wider context of black working class life, with sexual paranoia standing in for the treacheries visited on black men by Jim Crow and the American penal state. But some Jody stories have a more philosophical bent. “Jody, Come Back and Get Your Shoes” (1972), by Chicago soul belter Bobby Newsome, is a treatise on, as it were, Jody-ness—a dark warning that all men are potential Jodys.

In this world we live

You’ve gotta keep an eye on everyone

’Cause you never know who Jody is

Now, Jody could be the milkman

He could be the mailman, too

Jody could be your very best friend

Just making a fool of you

Still, it seems fair to say that Jody-ness is not equally distributed among the world’s milkmen and mailmen: There are Jodys, and there are Jodys. Consider comedian Rudy Ray Moore’s lewd “Jody the Grinder,” a rip-roaring evocation of superhuman sexual power that places Jody in the pantheon that includes Stagolee, Moore’s own blacksploitation alter-ego Dolemite, and other legendary black “badass” heroes. Or look at the cover of jazz trumpeter Horace Silver’s 1966 album, The Jody Grind: a jaunty Silver, wearing a sailor’s cap and a devilish grin, flanked by a pair of blankly beautiful women in mod dresses. It is an image of a magnificent rogue, a man whose amorality, guile, and seductive powers mark him as both execrable and admirable. Jody is a trickster, an antihero—the best, or at least most pleasurable, kind of hero to be.

But what does a mythic-folkloric black trickster-lothario have to do with a middle-aged white male journalist, frequently mistaken for a female one—the lone man included, alongside 209 women, in a Huffington Post slideshow titled “Vice Presidential Debate Reactions 2012: Women Sound Off on Twitter”? On paper, my antiheroic credentials are meager. (A true Jody, presumably, would have known what to do when Tanya started talking about sluts.) The cabbie in Hoboken insisted that I had “some Jody-ness” in me. Where is it?

The answer snapped into focus several years ago, when a Google search led me to the home page of Jody Whitesides, a singer-songwriter-multi-instrumentalist whose live show, according to his website, “is akin to a funky audio lap dance for your ears that sounds amazing and is captivating.” In a blog entry published in 2006, Whitesides addressed the question of his given name and made a confession. Although he’d been named Jody at birth, “from about 2nd grade all the way through graduating from University, people knew me as Joey.”

See I grew up in New York City. … There was a doll on the east coast market called Jody The Country Girl Doll. … They pandered to little girls via TV commercials and tried to make it as enticing as possible to city-bred girls who needed a rural void filled in their lives. What made this doll so annoying to me was the theme song from the TV commercial. … [T]he hook and chorus of it was so dopey, but so catchy, that other kids would instantly start singing the damn thing to me. Which then led to being called names and labeled as a sissy, for something I had no control over. I decided I needed to change my name [to Joey]. The moment I graduated from University I was like … I’m resorting to my birthname. Besides Jody just sounds like a cooler stage name and it’s my real name.

Reading these words, I felt a surge of pride, and of scorn for Jody Whitesides, emotions I could neither justify nor suppress. Unlike Whitesides, I am Jody and have been Jody, ever since my parents stuffed that albatross into my newborn’s swaddling blanket. I never called myself Joey—or Joel, or Colin. I bore up as choruses of “Sweet pretty Jody—the country girl doll” rained down on the schoolyard. I shrugged off the middling book review that Jody Rosen, authoress, received in London’s Sunday Telegraph. (“Her approach is intelligent but light.”) And unlike Whitesides, I didn’t re-embrace my name, when, years later, Jody suddenly seemed “cooler.” As Jody-ness in the Joe the Grinder tradition goes, it’s not much. But until a golden opportunity for antiheroism presents itself, it’s what I’ve got.

In the meantime, I’m Jody—a man with a woman’s name. It could be worse. Times have changed, and old stigmas have begun to melt away; a more tolerant society has brought greater openness about whether Dick might just as properly be called Jane. And like Whitesides, I’ve learned that Jody carries a certain cachet—that it can lend a whiff of the exotic to an utterly conventional man.

Besides, what’s the alternative? Not long ago, I spent an afternoon thumbing through a remarkable tome, The New Book of Magical Names, a reference guide and inspirational manifesto that claims to have “helped thousands find the perfect name for everything from their child to their coven to their cat.” The author, Phoenix McFarland, née Laurel McFarland, is a self-described “irreverent Wiccan priestess” and an advocate of name changing, a believer that each of us should hunt down our ideal name, the magical name that will wreathe its bearer in fairy dust. “Find a name that suits you and revel in it,” McFarland writes. “Roll around in its energies and get it stuck between your teeth, squish it between your fingers, immerse yourself in it. Let it work its magic on your life. Wear your name like a precious spell and be glorious in it!”

Far be it for me to disagree with a priestess, but my own tangled history leads me to a different conclusion. Could it be that we are best served by imperfect, not perfect, names? When a baby is saddled with a name, he is taught a first lesson about pitiless fate and life’s limitations—that there are aspects of the self that can never be self-determined, circumstances that must be stoically endured, and, hopefully, someday, made peace with. There are a goodly number of us who wear our names not like a precious spell but like a humbler workaday garment. Whatever you’re called—Jody or Sue or Moon Unit or Jermajesty or maybe even Anus—you can, if you’re lucky, reach that state of grace where you hardly notice your name is there at all. You wake up in the morning and slide right into it, like a well–broken-in pair of pantaloons.