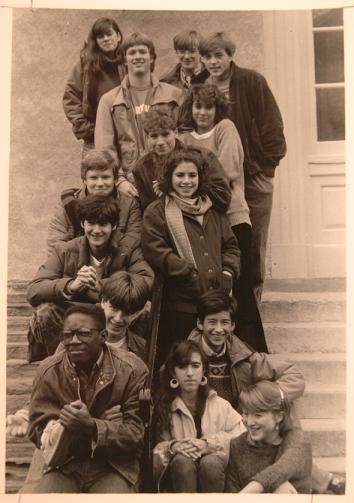

Andre Robert Lee is a talented filmmaker who also happens to be my high school classmate. So I sat down to watch his documentary, The Prep School Negro, with respect and pride, but also a bit of fear. This is our prep school at the center of the film: Germantown Friends School, a K–12 Quaker school in Philadelphia. Andre came in ninth grade as a scholarship student. I remember him as funny and outgoing and academically and socially successful. But what if he looked back on it all as misery? What would it be like to revisit those years through Andre’s eyes?

The answer is: moving and instructive. Prep schools play a tantalizing role in our education system, even if they don’t always realize their promise. The schools are a gateway to college, rewarding and well-paid jobs, and to power. Though they’re often thought of as places where the already wealthy and powerful groom the next generation, today most prep schools are committed to diversity, and that includes some number of low-income kids. Bringing in scholarship students is supposed to offer those kids a ticket to social mobility, and offer their more privileged peers the opportunity to learn alongside people different from themselves. Diversity benefits everyone, is the hope.

And yet all kinds of fumbling and fallout come with being “a guest in a strange house,” as one of the first black graduates of Germantown Friends, Joan Countryman, puts it. (Countryman is herself a distinguished educator.) Andre’s movie is about the prickly feeling that comes with being that guest. You should see the film because its subject—what it’s like to be a minority or poor in an elite institution—is one we don’t talk about nearly enough. (The movie has aired on PBS, and you can stream it here, or tune in for an online screening on Thursday at 7 p.m. Eastern that will include a Q-and-A with Andre and Countryman.)*

Andre crossed a divide each day on his trolley ride to school. On one side lay his poor black neighborhood in West Oak Lane, where he lived with his mother and sister. On the other lay GFS, a place filled mostly with students who took their privilege for granted. I don’t mean that GFS was a snobby or fancy place—Quakers are neither, and the families drawn to their educational ethos tend to be pretty open-minded, in my experience. Also, the school sits in a down-at-the-heels part of Philadelphia, not ritzy suburbia. There are no lush grounds or rolling hills.

But one of our classmates owned the factory where Andre’s mother did piecework. I didn’t know that growing up, but Andre did, and so did his mom, and it intimidated both of them. When Andre talked about her job, he hoped other kids would hear “peace worker.” His older sister, who did not go to GFS, says in the film that she felt like the school took Andre away from her. Andre too sees the distance he tried to put between himself and his family, and how it was laced with shame. “I remember we turned 16, it was time for cars, and [one of our classmates] turned the corner in the biggest Mercedes I saw in my life, and we didn’t have a family car,” he told me over the phone. “My mistake was to think, ‘their families are right, and mine is wrong, and I have to turn my back on my family and be like these folks.’ ”

A black teacher tried to talk Andre out of that feeling. “But at 16, you’re not going to listen,” he says. In a graduating class of 65, there were six “community scholars,” as they’re called. GFS started the program in 1965. Andre says it was the first of its kind in the country, and a model for others like A Better Chance and Prep for Prep. In our day, GFS identified candidates by talking to public school counselors and through a basketball and reading clinic. Today, the school also looks for kids at summer and afterschool programs like Breakthrough. Some kids get full scholarships and some get partial ones, based on financial need. (All told, 35 percent of GFS students now receive tuition assistance.) The community scholars program extends to the elementary school, and is funded by an endowment of about $6.6 million that GFS has raised.

In other words, this is a real investment for the school. And yet, the community scholars are not a critical mass. “The majority tends to have one perspective, and you feel on the other side all the time,” Andre says. For example, he remembers a discussion of The Communist Manifesto in 11th grade European History in which he rooted for the proletariat to knock down the ruling class. “I thought, ‘hell yeah, I totally get this!,’ ” he says. “But then other folks were like, ‘oh no, getting rid of the ruling class is not a good idea.’ And as opposed to understanding the text on a deeper level, I went right to, ‘I’m wrong, I’m the one who is misunderstanding.’ ” (Marx would disagree.)

How do you convert that kind of self-doubt into affirmation? Andre answers that question by moving from his past to the present of other black students, in several scenes shot a few years ago at another Philadelphia prep school, Penn Charter. We see the growing commitment to diversity that has become a marker of prep schools, though the price tag remains a big barrier for most families if their kids aren’t lucky enough to win a scholarship. In an English class, the teacher leads a discussion about a writing assignment in which students had to address this question: What does it mean to be white in the United States? One white student says she’d never thought about the question before. Another says “There’s nothing to write about because it’s nothing special.” A third says, “It’s just not a huge issue being white.”

A black student named Mike raises his hand. “It’s a privilege to be white in the United States,” he says forcefully. “You’re given respect. You don’t have to earn it, like other people do.” Before the bell rings, the teacher writes his words on the board, underscoring their validity, for her students and for us.

But Andre takes his movie beyond black kids asserting themselves and fitting in with white ones. He also delves into the rifts that class differences cause among the black kids. At Penn Charter, most of the black kids sit at the same lunch table. Andre interviews a girl named Brea, a black student who sits elsewhere, with her mostly white friends. She’s from Chestnut Hill, a traditionally white and wealthy neighborhood. “I feel really comfortable here,” she says of her school. “I see race. But I don’t really walk into a room and go, oh, there’s three black kids and there’s 15 white kids.”

But if Brea is comfortable with her white peers, she is less so with her black ones. The black kids in the cafeteria make her feel judged. “It’s a really intimidating table,” she says. “I always have to walk past them. It’s really hard sometimes. I get made fun of a lot.” She starts to cry. “They tell me, ‘You’re not really black.’ ” Then there is a boy named KJ, who was on partial scholarship, Andre told me. “In this community I’m considered real black,” KJ says. “But in another community, my neighborhood, I’m considered white-black for going to a private school.”

Despite the title of his film, Andre recognizes that many of the feelings he explores in it were not necessarily limited to black kids—nor was his experience the only black experience at GFS. Andre told me he recently had dinner with one of our white classmates, who’d been on partial scholarship at GFS, and he’d fully identified with Andre’s sense of isolation, and self-abnegating shame. Though he wasn’t black, as a kid who didn’t share the privileged background of many of his classmates, he too felt like an outsider. Whereas when I asked one of my black classmates, Bill Anderson, what he thought about the film, he wrote back:

I actually think that, although I enjoyed hearing and seeing Andre’s experiences, my perspective was almost opposite. Andre and others were immediately smacked in the face by how different they felt entering GFS. As a middle class, African American lifer, I lived in the somewhat artificial, diverse, liberal, open-minded environment that GFS created. I felt that I belonged and that society would view me the same way I was generally viewed within the walls of GFS. Andre’s eye opening experience was entering GFS; mine was leaving. … It was a difficult adjustment when I went out into the “real world” and realized that I would be judged for many things that were either non-existent or (more likely) not acknowledged at GFS.”

It’s the “not acknowledged” part that Andre’s film addresses. My deepest memory of prep school is the intense academic discussion, the plumbing of the depths of The Unbearable Lightness of Being, or Black Boy, or the Aeneid. But I’m not sure how well we plumbed our own depths together. That’s not easy. But Andre is asking prep schools to do a better job of surfacing the complexities of race and class difference, with both students and their families. That’s his message about how to make the strange house feel like home for all of its students.

Correction, Feb. 26, 2014: This article originally misstated the time for an online screening of The Prep School Negro. It will air on Thursday at 7 p.m. Eastern, not 7:30 p.m.