On Dec. 16, 1773, a group of young men dressed as American Indians dumped three boatloads of tea into Boston harbor. It was the most brazen act of a long campaign of political disobedience planned by the Sons of Liberty from the safety of the Green Dragon and Salutation taverns in the city’s North End. Today, you can still find the Green Dragon in the North End, a spiritual successor at the site of the original colonial tavern. But this Green Dragon is filled with throbbing music, making it a headache to plan and coordinate so much as a one-night stand (or so I’ve been told).

Sixteen years after the Tea Party, on the night of July 12, 1789, journalist Camille Desmoulins stood on a table at the Café de Foy and called on his fellow Parisians to smash the monarchy before it smashed them. The ensuing riot climaxed two days later with the storming of the Bastille. In the U.S. in 2014, you’ll find no shortage of urban cafés, but jump up on a table and you’ll break little more than the silence—and perhaps an unlucky Macbook Air. Then management will invite you to leave.

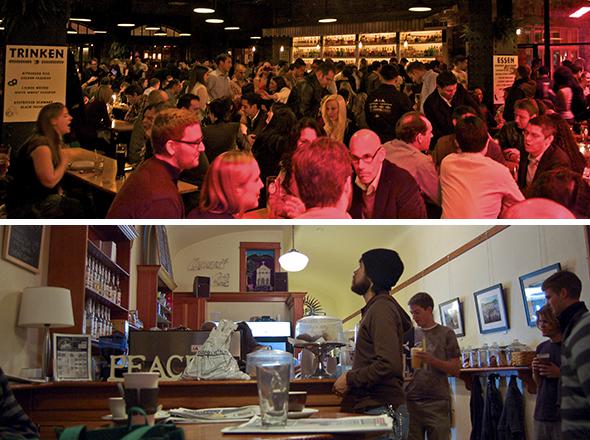

A noise gap has developed in American public life, and it’s a problem. The bars—at least those frequented by people under 40, who historically drive bottom-up political movements—have gotten louder. How loud? In 2012, the New York Times found that bars in that city regularly reached decibel levels so dangerously high that they violated federal workplace safety standards.

All that noise makes it hard to conduct a meaningful conversation, which is actually the idea. Bars have gotten louder at least in part in response to research showing that louder music encourages patrons to talk less and drink more. By rendering conversation obsolete, the loud atmosphere also nudges people towards imbibing past the point where intelligent conversation is possible. It’s not easy to find a large, crowded bar in an American city where conversation isn’t drowned out by music or a sports telecast. In fact, the Saloon, On U St. in Washington, D.C., has made its name by refusing to play loud music and forcing patrons to stay in their seats, making conversation possible.

The cafés, meanwhile, have gotten quieter. For centuries, coffee was used as a conversation stimulant. But in the present-day U.S., it functions primarily as productivity booster. Coffee long ago penetrated the workplace, and now cafés themselves have become workplaces—not just for eccentric writers and artists, but for knowledge workers of all stripes, who are often plugged into headphones that are plugged into laptops.

In 2011, a Gizmodo writer found it rude that people were talking near him at a café and tweeted, “Etiquette question: Now that coffee shops are basically office spaces, do you have to be quiet when you’re in them?” At the Bean in Manhattan’s East Village, as in several other other New York coffee houses, management has instituted a laptop-free zone. A few tables tucked in a corner of the shop, the Bean’s computer-free zone may as well be a memorial to the late, great café atmosphere.

The shift in both scenes amounts to more than just a loss for conversationalists. For centuries, bars and cafés around the world have fostered dissent and bottom-up political action. Cafés, especially, have bedeviled the authorities as long as they’ve existed. In 1511, worried about loose political talk stimulated by coffee, the governor of Mecca ordered all of the city’s cafés to shut their doors. In 1675, Charles II of England condemned coffee houses as sites where “False, Malitious and Scandalous Reports are devised and spread abroad, to the Defamation of His Majestie’s Government, and to the Disturbance of the Peace and Quiet of the Realm.” He ordered all of them disbanded by January. Neither ban proved enforceable.

In the history of the United States, the bars have played host to much of the action. Both the international labor and LGBTQ movements can trace their roots to American watering holes. The U.S. labor movement first took hold in the beer halls of industrial cities. The 1886 Haymarket Rally, which ended with 11 fatalities, was planned at Greif’s Hall in Chicago, a hotbed of labor agitation, by a group of anarchists and activists. Prosecutors went on to characterize the meeting at Greif’s as the “Monday Night Conspiracy,” and its participants were convicted as accessories to the murder of the police officers killed at the rally. The events inspired the communist and labor movements’ observation of May Day.

The LGBTQ rights movement began in earnest in the summer of 1969 with a rebellion against a police shakedown at the Stonewall Inn, a mob-run gay dive bar in Greenwich Village. Though the Stonewall riots were spontaneous, much of the organized movement that sprang from them was planned at gay bars from California to England.

This isn’t coincidence—a variety of factors have made bars and cafés the spaces where potent political change begins. Alcohol loosens inhibitions and caffeine stimulates conversation. The spaces offer a meeting place for people who don’t have access to private clubs, boardrooms, and the halls of power—people, in other words, who are less invested in the status quo. Crucially, these are also semi-public spaces that can deliver a measure of privacy, a place where it’s easy to congregate yet hard for authorities to monitor.

But that sweet spot can only be achieved at a certain level of din: A bar or café needs to be quiet enough that you can engage in conversation but loud enough to create both the perception and the reality that you won’t be too easily overheard by the wrong people. (Not that the authorities won’t try. Louis XV’s spies haunted the cafés of 18th-century Paris. The NYPD’s controversial 21st-century infiltration of Muslim neighborhoods in New York City and beyond sent plainclothes officers to spy in cafés where they eavesdropped on conversations about politics, cricket, and kebab.) It’s this din, created by a large number of people closely congregated and engaging in regular conversation, which has been increasingly hard to find in our coffee houses and beer halls.

In part, the noise gap has developed because the Internet has become our new gathering space. A lot of those people ignoring their neighbors at cafés are on their computers, and some of them are surely using those machines to engage with politics. (The FBI has asked Internet café owners to report suspicious customers, defined in part as people who “always pay cash” and “are overly concerned about privacy,” as potential terrorists.) But the Web cannot play the same role as bars and cafés. It can’t match the intimacy of those physical spaces or their potential for spontaneous mass gatherings. For all the hype about social media’s role in the Arab Spring, cafés still played a role, and an important one. Al Jazeera presenter Hassan Ibrahim has said of Egyptian protestors, “Electronic media, and the Internet played a vital role, but actually, they met in coffee shops. All political movements in Egypt started in coffee shops.”

It’s also much easier for governments to tightly monitor online expression, as revelations of the NSA’s extensive Internet penetration have underscored. In 2012, the government compelled Twitter to turn over thousands of tweets from an Occupy Wall Street protestor charged with disorderly conduct. The tweets bolstered the government’s case, and the protestor pleaded guilty lest they become public at trial and incriminate other Occupiers. The Internet is not always an environment conducive to civil disobedience.

Perhaps this is why we haven’t seen a bottom-up political movement agitating to break our country’s political paralysis. Much has been made of Washington lawmakers’ changed social habits. Their short workweeks and the permanent campaign push them back to their districts on weekends. They no longer mix at Georgetown townhouses or over bourbon-fueled poker games, and so, the theory goes, across-the-aisle deal-making doesn’t happen. But the same social insulation affects average citizens as well. The rest of us sip coffee and beer right next to our neighbors without the opportunity to take each other’s confidences, shout about politics, or engage in acts of spontaneous persuasion.

In the wake of a financial crisis and in the face of a sclerotic federal government, we might have expected a political upheaval in recent years in the U.S. Instead, we got the Tea Party and Occupy. Today’s Tea Party emerged in part from the Koch Brothers’ boardrooms, not a tavern, and it’s no wonder that the putative grassroots movement has had the primary effect of contributing to more gridlock, installing obstructionist legislators, and discouraging moderates from participating in deal-making. Occupy managed to insert income inequality into the national dialogue, but the carried interest loophole still enriches hedge fund managers while Congress cuts food stamps for the poor. After the movement was pushed from the open-air spaces it occupied, it lacked another space in which to build on what momentum it had.

We’re left with a political system in which our Congress is near-universally reviled, and yet its incumbents can generally expect to remain in power. Sure, not everything that comes out of the bars and cafés is to the good. The Beer Hall Putsch, in which the Nazis tried and failed to seize control of Munich, was Hitler’s stepping-stone to power. Desmoulins, after inciting the storming of the Bastille, eventually succumbed to the guillotine in Robespierre’s reign of terror. But the guys who planned the Boston Tea Party over rum punch decided that allowing for the possibility of periodic upheaval was an important part of their democratic experiment.

The current upheaval in the Middle East, it’s worth noting, is often playing out in cafés. The first cafés in the world sprang up in the region some time between the mid-15th and early 16th centuries, and they continue to serve an important political function. As Billie Jeanne Brownlee, a scholar of Middle East politics, wrote last year, “Unlike in the West, the Internet has not turned people into antisocial creatures; quite the opposite, it has turned these cafés into places where information found on the web is shared face-to-face between friends.” The New York Times found “the spirit of the Arab Spring” alive and well last year in a buzzing café in Tunis. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that the owner of Washington’s most conversation-friendly bar, Saloon proprietor Kamal Jahanbein, was born in Iran. The Washington Post has dubbed the establishment “a true chat room.”

Maybe all this country needs to deliver the periodic rebellion the founders counted on is a few more good proprietors willing to get Americans talking, confiding, and subverting again. I’d drink to that.