Surely one of the greatest downsides of becoming an adult is the disenchantment of summer. Yes, it stays light out longer and many of us get a week or two of vacation; but, in general, the magic and tantalizing potential that those warm months held in our youth is gone. Perhaps one of the most sorely missed charms is the venerable summer job, those short-term experiments in employment that provide not only a little spending money, but valuable life lessons as well. So, with Memorial Day just behind us, and the season officially in full swing, we pay homage to the summer job with a series of recollections—some traumatic, some glowing—from Slate staff. Please enjoy, and if you feel moved to share your own tale, follow the instructions at the bottom of the page.

***

The Art Shack

I worked in the Art Shack of the Chilmark Community Center on Martha’s Vineyard. Imagine the most privileged children in the country kneading clay into your hair. One kid was prematurely world-weary and just sat in the corner eating papier-mâché. At least I learned how to braid hemp!

–Katy Waldman, assistant editor

The Poisonous Pachysandra Patch

My first summer job was the summer before I started college. Because I hadn’t found anything better (or, in fact, looked for anything better), my father arranged a job for me as a groundskeeper at a local apartment complex. Most days I mowed and trimmed lawns and worked myself into a nice nasty sweat in the humid D.C. summer weather.

One particularly hot day, I was given the task of weeding a patch of pachysandra. Since pachysandra thrives in well shaded areas, that’s exactly where this patch was located. Shade beats sun.

“Just watch out for the poison ivy,” my supervisor instructed me. “You know what it looks like, right?” Of course I knew what it looked like: I was a Boy Scout, and camping in the woods had been a part of family vacations since I was very young.

Humid weather, though, is humid weather whether you’re in the sun or in the shade. As I weeded, I wiped my brow with my forearm to clear the sweat. Of course, within hours a poison ivy rash had broken out all over my face.

The next summer I signed up with a temp agency to do miscellaneous office jobs.

–Doug Harris, Slate’s chief architect

Herding Brats

Ever since puberty, I haven’t been a fan of young children—I don’t indulge them, and I don’t like being around them. So it was probably a bad idea for me to apply for a job where I would have to spend several months with them on a daily basis—but it was the summer between my sophomore year and junior year of college, and I needed something that would both look good on my resume and pay me well.

I spent June through August of that year, five days a week, 12 hours a day, at a performing arts camp in Chicago, and it was by far the worst job I’ve ever had—though to my 19-year-old self, the paycheck seemed big enough to make it worthwhile (at first). After applying to be a choreographer with the preference of working with teenagers, I was hired as a mere camp counselor, tasked with shuffling a group of 5- to 8-year-olds from activity to activity for the majority of my employment, which required no creativity whatsoever (unless you consider figuring out how to deal with a 6-year-old who isn’t potty-trained “creative”).

Sadly, the majority of the youngest kids were there only because their (usually wealthy) parents had nowhere else to put them while school was out, and they didn’t really want to learn how to do a kick ball change or sing about how the sun will come out tomorrow. They didn’t pay attention, and many misbehaved. One deceptively adorable 6-year-old girl was actually a brat who would scream any time she didn’t get her way. She seemed to know she was cute, and she would bat her big brown eyes in the hopes of melting my heart rather than getting sent to time out. (It never worked.)

To top it all off my boss, the camp founder was kind of a creep among a staff made up almost entirely of women—he once asked me if I was dating anyone, and then wondered aloud how it could be that I was single. Thankfully, this particular summer camp no longer exists to make young college students like me want to pull out their hair. I’ve since learned that my former boss shut the operation down and disappeared soon after, accused of fraud.

–Aisha Harris, Brow Beat assistant

Photo by Jessica Rinaldi / Reuters

Gardening, Good and Evil

The summer just after high school, I got a job as a gardener on the enormous estate of a tech mogul who lived in my hometown. The gardening staff numbered about eight—half full-timers, half summer scrubs like me. We worked in sweltering heat and pouring rain. I was the unhappiest and worst gardener in the history of gardening. Yet I somehow lasted the summer, neither getting fired nor harming myself with pruning shears.

Here were my assigned duties, ranked from dreadful to tolerable:

Weeding. If you’re in an office right now you can replicate this task. Get down on your knees. Hold your face close to the Berber carpeting. Now pick bits of lint out of the carpet and place them in a bag. No, don’t stop. Keep doing this. FOR THREE HOURS. Also, for the sake of realism, you might arrange to get rained on and have ants bite you.

Edging. You can define a pleasing edge on a flowerbed by cutting a deep furrow, lining it with a plastic retaining wall … oh, I’m bored just describing it. The important thing to know here is that the motorized edging tool is a wildly spinning blade that can hit a rock, jump erratically, and define a pleasing edge between your ankle and your foot. I lived in constant fear of de-foot-ment.

Watering. Hold a hose and aim a spray of water at the base of various plants. This felt like when you need to pee really bad after a long night of drinking, only instead of taking a minute or two this took a full hour and offered zero feeling of physical relief.

Mowing. I hated carefully mowing the chessboard patterns on the “show lawn” at the front of the mansion. But I did enjoy careening around on the riding mower, grinding up huge swathes of open meadow. Don’t make me feel guilty about the cloud of butchered grasshoppers floating in my wake.

Backhoeing and dump trucking. The badass side of gardening. You’ve not known true bliss until you have operated heavy machinery as a teenage boy. I’d scoop up giant globs of mulch with the backhoe (just like an arcade crane), plop them in the back of the dump truck, drive through the hidden reaches of the estate listening to loud rap, and then dump an avalanche of bark chips in the precise wrong spot—thus killing a rare and beautiful $6,500 plant. Pure delight.

The next summer I was a telemarketer, which was in some ways better but also made me want to self-harm with pruning shears.

–Seth Stevenson, contributing writer

Health Grade … Pending

The summer after my sophomore year of high school I was hired for a job at America’s finest music/food/pale-upper-arm festival, Milwaukee’s Summerfest. I was to work in the Fest outpost of a niceish suburban restaurant in what I believed to be a position as a cook or a register guy.

Instead, on the broiling-hot first day of Summerfest, I was taken to a windowless, stifling room behind the kitchen and given an apron and an enormous recycling-bin-sized tub of raw, oozing steaks. “You need to pound those flat,” said my boss, who I realize now was like 23, max.

I looked around the room. “With what?” I asked.

“We usually just use these,” he said, pointing at the big 128-ounce cans of diced tomatoes stacked on the shelves above the counter.

And so for five hours I pounded steaks, over and over, with heavy, slippery cans that had, presumably, just been removed from the dusty, mouse-infested storeroom where they’d sat since the summer before. I washed my hands, sure. But did I wash the cans? The counter? Nope. Hour after unrefrigerated hour the level of steaks in the tub lowered as I splattered the cans, the counter, the shelves, the wall, the ceiling, and myself with blood. I took a short break, during which, God help me, I ate a steak sandwich from my restaurant. Then back to the smashery I went.

At 4 p.m. I took off my apron and threw it into the corner. I scrubbed my hands and arms and told my boss I didn’t think this job was for me; he shrugged and handed me a $20 bill. I’d made plans to meet friends that afternoon, and I shall never forget the looks on their faces when I sauntered up to them at the entrance, dripping with gore, my shirt and shorts and socks and shoes drenched in blood but for an apron-shaped area on my front that was merely drenched in sweat. After an hour I could no longer take my own stench and I threw my clothes away in a public bathroom, changing into a Summerfest-branded T-shirt and shorts I’d purchased at the Fest. Their cost: $25.

—Dan Kois, senior editor

Porta Potty Paparazzi

When I was 19, I worked as a waitress at an upscale restaurant in a New England vacation town that had its share of wealthy and famous visitors. The restaurant was owned by a couple—the husband was a sweet, mild mannered chef, and the wife was a mean-spirited, venomous manager. Every shift she hissed insults and criticisms about all the things I was doing wrong, from how I cut lemons to how I wrote out checks, to how I greeted the guests. Once, while I was in the middle of taking a table’s order, she walked by and swatted me on the legs because, as she later explained, “I didn’t like how you were standing.” When she was out of earshot, the other servers and I meanly joked that her then toddler who’d been a preemie must have come early in order to get as far away from her as possible.

A pet issue of the owners’ was how the water service in town was extremely expensive, and they therefore insisted that only customers could use the bathrooms. This limitation included not only noncustomer walk-ins, but also the staff as well—we were all invited to visit a Porta Potty in the parking lot should the need arise. One empty afternoon after lunch service, I heard a familiar voice as I was putting away silverware. Across the dining room, I saw that it was Meg Ryan, politely asking the Jamaican line cook if she could use our bathroom. I stood open-mouthed as he nonchalantly explained (as he had many times) that per the bosses’ orders, the bathrooms were for customers only; she could use the Porta Potty outside. Meg Ryan said thank you and headed out to the parking lot to take the cook’s advice. I rushed over to gab with him about how he’d just denied a movie star use of our bathroom, but he’d never heard of her. When we told the owners the story later, they were thrilled—that he hadn’t broken the policy, even for a Hollywood starlet.

—Katherine Goldstein, innovations editor

We All Scream for Ice Cream

In my small Ohio hometown, there are a few inalienable truths within city limits: Football is king, pitch is superior to all other card games, and Flub’s Dari-ette—where I spent my high school and early college-era summers—is the best summer treat in town.

I began working at this mom-and-pop soft-serve joint after my friend Kara saved me from a miserable job at a local grocery store bagging groceries and collecting carts—a job my parents required I get in order to maintain my driving privileges. When Jodie, the owner’s wife, told me I had the job, I nearly tackled her with a bear hug. I spent the next five April-to-October seasons serving cones and milkshakes, debating with co-workers and customers whether it’s sher-bet or sher-bert, developing a code for identifying cute boys in our lines with the all-female Friday night crew, and trying not to lose my cool while explaining to a customer for the umpteenth time why we didn’t have blue raspberry sherbet on that day.

Nowadays, I not-so-secretly love going to DIY frozen yogurt shops and flaunting my soft-serve pouring skills. I worked at Flub’s in the days before the store installed cash registers and credit-card machines, and I can still calculate change at lightning-fast speeds sans calculator. And I’m pretty sure my favorite pair of shorts still smells like hot fudge and whipped cream.

So if you ever find yourself in Hamilton, stop at Flub’s and order a No. 32: Meg’s Fudge Brownie. And, for the record, it is not possible to get sick of ice cream.

—Meg Wiegand, copy editor

Learning the “Hippie Punch Dance”

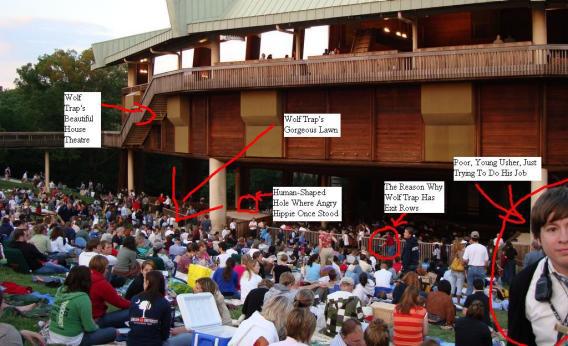

During the two summers after I graduated high school, I worked as an usher at Wolf Trap, an outdoor concert venue in Washington D.C. It was a great job with great people, but at times it felt like I was a professional NARC. No more was this the case than during an epically hard-to-usher performance by the jam band The String Cheese Incident. Part of my job was to keep a fire lane between the lawn seating area and the house theater clear as a general exit and in case of emergencies. This involved walking back and forth asking hippies, who didn’t care for my rules, man, to please stay behind a line of tape that was the designated “dance line.” This task was impossible.

The usual response was for the hippies to dance behind the line for a moment, wait until I went away, and return to taking up the entire fire lane as a fun-time jam floor. One tall, obviously stoned hippie chick in a flower dress tried to dance with me, ignoring my meek requests for her to “please, stay behind the dance line.” Another tall, well-built, shirtless hippie wearing flip-flops and a beaded necklace thrust his swinging, balled-up hands toward me like he was approaching to dance, but instead punched me in the chest, before receding back into the gyrating heap of sweaty, smelly hippie humanity. I wasn’t hurt, but I was shell-shocked. Had that hippie just assaulted me? Weren’t they supposed to be a peaceful people?

Later in the evening, I saw that angry hippie had climbed atop a sound box at the back of the house, and was doing his angry hippie punch “dance” up there, a major safety concern. My friend and colleague Vyque had climbed up on to the box to try to get him down, and I saw angry hippie smile really weirdly and slowly walk toward her. I started to climb up the sound box to try to help her out, but when I peeked my head back over the top of the box, angry hippie was nowhere to be seen. It turns out he had walked directly into a hole in the sound box and fallen a full story to the bottom of a flight of stairs. I ran to go get him a wheelchair, a task made immensely more difficult because of all the dance-line violating hippie groovers. When I finally got back, I learned that when Vyque tried to help him, angry hippie had slapped her and said “you tried to kill me, bitch!” EMTs finally showed up and wheeled him out of there through the chaotic dancing hippie morass. He probably just had a broken ankle, but I like to think that angry hippie lost the foot because we were unable to get to him in time.

—Jeremy Stahl, social media editor

Courtesy of Bill Adler

Summer Temp-tations

One summer when I was in college, I signed up with a temp agency as a typist. I was sent off to the Houston-Galveston Area Council, an association of local governments, to do data entry in the accounting department. The people in the office were funny and very nice to me, but they fulfilled every caricature of public employees. They worked as little as possible. They hired me to do stuff they should have been doing. They told me to inform the temp agency that I was done with my work there, and then, off the temp agency’s books, they kept me on the job and paid me the extra. At some point they figured out that a bunch of furniture was being stored in one of the offices, available for the taking. So they took it.

The guy who ran the department was the controller, Bill Prince. His door was closed all day. It sounded like he was on the phone. When I asked about it, somebody told me he was actually running his own carpeting business while he was at the office. I had figured he was just doing what everybody else did—slacking on the job. But in his case, he was using his free time to make some money on the side. At the end of the summer, I asked Bill for a letter of recommendation, and he wrote one for me.

Some time after I got back to college, I saw an item in the Houston Chronicle. It turned out that Bill’s carpeting business wasn’t a business. It was a front within a front. He was convicted of massive fraud and embezzlement: writing $338,000 in checks from HGAC to a dummy entity that passed $264,000 back to him, and stealing more than $1 million in federal funds.

I posted the article, along with Bill’s letter, on my dorm room door. As far as I knew, I was the only kid at school with a job recommendation from a convicted felon.

—William Saletan, columnist

Will Work for Food

It was 2009, and though two months after I finished they would be shut down, I landed the first—and most delicious—editorial internship of my career at Gourmet Magazine. On my first day, I was given my own cubicle and a tour of the test kitchens across the hall from the famed Condé Nast cafeteria. The week before I had watched every video on the site, so I ended up knowing all the staff by name before I was introduced to them. Of course, out of awkwardness and politeness I pretended I knew nothing about their favorite technique for kneading bread. I sat in on meetings, and, as the only vegetarian in the office, was always given first dibs on dishes that fit my dietary restrictions. It was a filling nine weeks.

Midway through the summer, the assistant of editor-in-chief Ruth Reichl went on vacation, and I somehow ended up filling her seat while she was gone. I was told not to worry: Ruth wasn’t “devil wears Prada” or anything. And it’s true, she wasn’t. She was great. But I was nervous: I had never answered a phone call from Francis Ford Coppola before. Still, I felt pretty powerful for a 22-year-old. Of course, I did have the typical intern-y tasks, like cleaning out the storage closet which housed issues dating back to the ‘40s and various other Gourmet paraphernalia—including the poster-size covers of the most recent issues that hung in the hallway until they were replaced. I was told to recycle them, and I did, until one day I decided to take one home. I still have August 2009 hanging in my apartment, and not a day goes by that I don’t crave ice cream sandwiches.

—Miriam Krule, copy editor and “Faith-Based” editor

Physics for Poets

Oscar Wilde once wrote that “we can have in life but one great experience at best, and the secret of life is to reproduce that experience as often as possible.” I’m not as pessimistic about the numbers, but when reflecting on summer job’s past, there is definitely one experience that I always return to as a measure of greatness.

The summer after my freshman year of college, I miraculously got an internship in the communications department at Fermilab, the particle physics lab outside of Chicago that was, back before the LHC, the premiere spot for smashing protons/antiprotons in the world. Part of the deal was that my fellow intern Lauren and I would live in lab housing on site among visiting international physicists, so this was something of an immersion experience. I wish I could tell you what it’s like to play beer pong with some of the most scarily brilliant people on Earth (people who, when arguing about the fundamental nature of reality, actually have graphs to back up their slurred pontifications). But this being a government lab, those stories are classified.

What I can talk about is the time Lauren and I made cookies iced with neutrino symbols for our friend who was monitoring the detector on a night shift, or how I was suddenly trusted to interview Nobel laureates about the mysterious equations on their blackboard walls. I may also mention how my editors patiently taught me to structure an article and sifted through my copy to recover misplaced modifiers. There’s also the early evening drive back to the lab’s “village” with the windows down, listening to “Glamorous” on the mix CD we played all summer, or the time I cooked shrimp and grits for some Italian researchers who were kind enough to ignore my ignorance of polenta. And, of course, I’d be remiss not the mention how, as a parting gift, the stern, exacting department director gave me a yellowed collection of Oscar Wilde quotations because she somehow sensed that I might find them meaningful one day.

To say that this was a paid internship may be an understatement.

—J. Bryan Lowder, editorial assistant for culture

***

Now Slate wants to hear your summer job stories! Do you look back lovingly on your summer of lifeguarding, or do you still have nightmares about the months you spent waiting tables? Email us at submissions@slate.com to tell us about your best or worst summer work experience in 200 words or less. The best entries will be featured in a follow-up article.