The Spring Riot of 1963 flashed across cultural history like a pyrotechnic burst of wanton Americana. It lit on the campus of Princeton University on the first Monday in May and blazed up the Northeast Corridor, peaking in intensity on May 10 at New Haven where the boys exchanged beatings with the cops. For months thereafter, its smoldering wreckage filled sensational space in the national press as tens of millions of adults opened their morning papers to confront a generation gap and a moral panic. Old schools shivered in a cold sweat of spring fever—a case of student protest gone viral. Viewed in retrospect 50 years on, the Spring Riot of 1963 is a pivotal event, a violent insurrection, a preview of coming destructions. But the men and women who in later years occupied Hamilton Hall or picketed Dow Chemical in Madison or died at Kent State were bona fide student demonstrators. The boys who in 1963 roughed up some pretty campuses were rebels with a cause unmentionable in polite company. The student rioters of ’63 demonstrated the temper of the times, unconsciously fighting a guerilla skirmish in the sexual revolution.

That first Monday in May, the 6, followed Houseparties, Princeton’s annual spring formal, where, four decades earlier, when former student Scott Fitzgerald was at his hottest, he and Zelda had shown up as “chaperones,” brawling and cartwheeling. The women imported as dates for a weekend of booze and noise had returned to Smith or Sarah Lawrence or the Main Line or wherever, and the undergraduate campus reawakened to fairly dull life in a superlatively dull town in middle-of-nowhere New Jersey, under the in loco parentis supervision of an administration that never let you take the car out. The campus of Princeton had imbalanced hormones that Monday when the Spring Riot of 1963 began, around 10:30 p.m., as a small bit of study-break tomfoolery. That opening chapter ended two and a half hours later, after the crowd had peaked at an estimated 1,500, and after failed missions to gather lingerie from women boarding at both a nearby choir college and at Miss Fine’s, a prep school. Final tally: Tens of thousands of dollars in property damage, 644 marks on permanent records, 47 suspensions, 14 arrests, 13 convictions.

And then the thing leapt. That week, Students at Harvard, Columbia, and Brandeis made efforts at sympathy riots, but these never amounted to much more than half of the student body wandering around after curfew in a futile search for trouble (unless you count the May 19 aftershock initiated by Radcliffe women roaming Cambridge in search of jockstraps).

In Providence, R.I., and New Haven, Conn., the native spirits were more restless. One night that week at Brown, a frat boy accidentally broke a window with a softball, then his peers very intentionally broke some more, setting a tone for the next five hours. In pursuit of women’s underwear, members of a mob of 1,500 approached women’s residences at Pembroke College and at RISD, and the cops weren’t having it—15 arrests, nine police dogs.

At Yale, as many as 2,000 boys picked up the same act early on May 10, with the New York Times reporting:

“This morning, soon after midnight, freshmen left Vanderbilt Hall and began shouting on the campus. Upper classmen joined in, and the students marched in the streets toward Helen Hadley Hall, Yale’s only dormitory for women. They found the police barring all approaches to the dormitory.”

But to get the full effect of the moment, you had to pick up the Herald Tribune, which was not too decorous to report the marchers’ chant, “We want sex! We want sex!” Turned away at Hadley Hall, the boys regrouped, went downtown, and engaged in melee with police that produced 17 arrests and put significant mileage on at least 50 billy clubs.

That following Sunday, the Times editorial page greeted the Princeton riot with an entitled chuckle. Merely amused, the editorial, headlined “Elementary Rioting I”, boasted with “nostalgic pride” of the havoc wrought by “greying veterans” of the campus mayhem scene. The Times suggested that colleges develop curricula for how-to-riot classes “to run for one week every spring on every American campus. Those who flunk the course would be required to repeat, annually.”

Meanwhile, the relevant editorial in the Herald Tribune headlined the riot as “Sleazy Kid Stuff,” joining the populist indignation expressed by Hearst columnist Bob Considine: “These bums should have been locked up and booted out of school. If 1,500 Puerto Ricans had run similarly berserk in New York … the full weight of the law would have clobbered them.” However, elsewhere the Herald Tribune shared the Times’ regal indifference. The reporter who transcribed the we-want-sex detail compared the Yale event against New Haven’s history of wanton rampages and declared himself unimpressed.

The man from the Herald Tribune did not see that the energetic brutality of the Spring Riot was different in kind and in context than its predecessors. In a world that was going electric and egalitarian, a youth culture was finding its voice, and challenging an establishment with bodily force, using the rhetoric of the old-school boys-will-be-boys prank. Which was rather an ill fit when contrasted with the news from Birmingham, Ala., of the disenfranchised being attacked for praying in the street. Witness the Daily Princetonian’s headline about the conclusion of the Spring Riot—“Yale Riot Marred By Police Brutality,” as if the cops had spoiled all the fun by preventing total chaos.

It first struck me as odd that the Herald Tribune reporter missed the mark, because his byline read Tom Wolfe. But that was a long time ago, and there weren’t yet any Tom Wolfe books to guide him through the strange rearrangements of American society in the 1960s. The Spring Riot of ‘63 was a freak footnote in the histories of co-education and the sexual revolution, of the Establishment and its bourgeois manners, of public assembly and private social life.

***

To follow the all-American tradition of the panty raid back to its deepest origins would require detailed reference to pagan fertility rituals. Let’s instead pick up its pre-history at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in the 1920s, where a “Spring Riot” was an annual event that “broke out spontaneously on one of the first warm evenings.” Among other horseplay, the boys would invade the girls’ residences, asking for underwear. The classic imagery finds co-eds cramming sorority-house balconies and dorm-room windows, raining their silken scanties upon crew-cut heads, along with occasional water balloons, and sometimes a potted plant. The administration at Illinois tolerated this gentle mayhem as a healthy expression of vernal exuberance.

The first significant stand-alone panty raid swung into action at Augustana College in Rock Island, Ill., at a quarter to 1 in the morning on Feb, 25, 1949. The Augustana incident isn’t strictly representative of the form; it had the character of military action (as when the vandals conspired to cut the power lines leading to relevant dorm and solicit the collusion of a housemother). Still, the Chicago Tribune’s front-page response—“Students Don Masks, Invade Rooms of Sleeping Co-Eds”—suggested a template for newspaper editors who wanted to have their sensationalism and stoke a moral panic too: The paper claimed that some of the girls “became hysterical,” and for balance reported that “others were heard calling out windows, ‘Help! Police! Isn’t this wonderful?’ “

The first proper, impromptu panty raid came on March 20, 1952, and the account of the alumni magazine of the University of Michigan depicts all the classic tropes. After dinner on a warmish weeknight—57 degrees in Ann Arbor—a junior picked up his trumpet and tootled a bit of Glenn Miller from his window, just to relax. A trombone responded from an adjacent quad, and two tubas, and students started yelling at the instrumentalists to shut up. A general racket gathered, and soon 600 guys were milling around. The arrival of campus security provided further stimulant. Michigan Today anatomizes the environment:

“Stop here and review the ingredients: a) the first comfortable night outdoors in four or five months; b) a great deal of ambient noise; d) a strict code of rules forbidding unsupervised mixing of the sexes; and d) hundreds of 18-, 19- and 20-year-old males.”

Boys raced through girls’ dorms, and the girls attempted a counter-trespass, and 2,500 kids ran lightly amok, until at 1 a.m. it started to rain, wetting the fuse just as things threatened to turn incendiary. A witness recalled the fun and games beginning to degrade “into unpleasant demonstrations of near-viciousness.”

In 1952, Michigan’s case of spring fever went viral, and that May it swept the nation like an epidemic afflicting a majority of the undergraduate institutions you’ve ever heard of. Minnesota, Missouri, Barnard, Vanderbilt, Kansas, Florida, Nebraska, Iowa, Purdue, Alabama, Wisconsin, Oklahoma, Vermont, and so on. All over the place, boys stormed girls’ dorms, damaging property while demonstrating impropriety. The phenomenon peaked on May 21, when a survey of wire reports indicated “in the last 24 hours, an estimated 12 thousand students raided women’s dormitories on at least 11 of the nation’s campuses.” Ask your grandma to be sure, but it appears that the tenor of the true ’50s panty raid tended more toward reciprocal consensual flirtation than attempted sexual assault. Surely a broad range of impulses made themselves felt. Asked for his take, Alfred Kinsey observed, “All animals play around.”

In her social history Sex in the Heartland, Beth Bailey takes care to distinguish this kind of nonsense from the sort of organized student activism that argued against strict curfews and parietal rules. “Panty raids were in the tradition of carnival, not of revolution,” she writes. And yet the point remains that “campus panty raids subverted middle-class mores and defied the authority of adults.”

Imagine being the typical 20-year-old American-male college student in May of 1952. You have come of age in the new era of the American teenager. You are living in close quarters with thousands of peers amid a campus boom made possible by the GI Bill. Whether you study rocket science or history, you are being trained to win the Cold War. You are eligible to be drafted to kill and die in Korea, but you cannot vote, and you cannot spend the night with your girlfriend, and you cannot console yourself by rocking out to “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” because Mick Jagger is still 8 years old. Which is not even to mention that homosexuality is grounds for expulsion. You have been waiting for spring. You have been studying Robert Herrick in English lit. The leaves are on the trees. The sun is in the leaves. The personal is the political, but there aren’t yet any second-wave feminists to say so. The sap is rising in the trunk. The panty-raider’s pursuit of unmentionables is sometimes a conscious act of political speech, sometimes the unconscious expression of teen lust in a repressive climate.

There was never again a panty-raid season like ’52, though isolated incidents of like behavior became a feature of college life. By and large, the tone was of the rumpus, but now and then, a ruckus broke out. On Wednesday, May 16, 1956, temperatures in Berkeley reached above 90 degrees, and at the University of California, the frat-house water fights of the smoggy afternoon led first to good-natured after-dark frolicking and then, after hours, to belligerent groping and general hysteria. Guns were drawn, and battle lines. The Chronicle’s headline: “2,000 At UC Go On Wild Spree.”

That was Berkeley’s first panty raid. Chancellor Clark Kerr’s 33-page white paper on the affair concluded that (contrary to the reports of Newsweek) no women had been disrobed, but estimated losses of $12,000 in damaged property and stolen underwear. Kerr convinced a donor to kick in $300,000 for a new pool, and he cautiously anticipated a peaceful future, as in these remarks quoted by Seth Rosenfeld: “I have considerable confidence that the current generation of students at Berkeley will not again engage in such activities.” He added: “It is perhaps too optimistic to believe that there will never be another major mass disturbance by Berkeley students.”

***

There are nine colleges with traditions of campus revolution predating the American Revolution. It happens that May 3, 1963 saw the Harvard Crimson recap that school’s history of insurrection; in 1780, the Tory student body forced the resignation of the university’s Loyalist president—but mostly there were tantrums about cafeteria gruel, which occasioned mock-epic poems about month-long food fights. Once a century or so, Yale has an out-of-hand snowball fight. Everybody knows about the animals at Dartmouth.

And all of these things were happening at good schools. The long and dense tradition of rogue behavior at Princeton is such a marvel partly because the school, despite the best efforts of Woodrow Wilson, didn’t start getting good until after World War II. This is one reason that its president was so sensitive about Scott Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise portrait of the school as “the pleasantest country club in America.” Soon after its publication, Fitzgerald received a very strange letter from John Grier Hibben: “I am taking the liberty of telling you very frankly that your characterization of Princeton grieved me.” That letter was dated May 27, 1920, two weeks after students opened up Houseparties Weekend by burning down the chapel. (To be clear, no arson charges were filed, but an afternoon’s study of the matter will likely lead you to conclude that the kids were burning down the examination hall in the hope of getting out of exams and the chapel was just collateral damage.)

That May Monday, around 10:30 p.m., the innocent noodling of a study-break clarinetist came drifting from a window in Henry Courtyard. A trumpet honked reply, a trombone came in, as did vocal razzes and verbal jeers, building to a general clatter of instruments, phonograph records, fire alarms, cranked sirens, cherry-bombs, the rustle of toilet paper in the elms, the crackle of burning ivy on the old stone walls. The authorities appeared, nudging the mob to the town’s main drag.

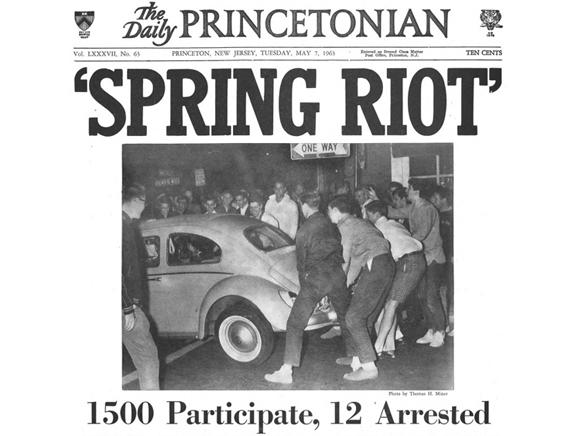

Scholars of mass psychology promise that any proper spontaneous crowd will direct itself to the space where it can make the most noise. In Princeton, this meant Nassau Street, where the crowd grew to 1,000 young men, who barricaded traffic with bike racks, trash cans, and park benches. When the cops showed up, the boys applauded and barked at the police to sit. On May 7, the front of the local section of the New York Times featured above the fold the very VW you see above the fold here. The guys are moving the car and its passengers to the sidewalk.

Further highlights of the evening included trampling the university president’s estate; wheeling a one-ton air compressor down the steepness of Washington Road, where it missed a car and met a lamppost; smashing all the windows of the two-car commuter train; and lighting the Nassau Street barricade aflame and wandering back and forth in front of it, glassy-eyed and looking for action.

Princeton houses its archives at Mudd Library, where a visitor can discover any number of fascinating Spring Riot documents. At the moment, I’ve got two clear favorites. One is a Daily Princetonian article summarizing a magazine’s report on the event, which surveyed psychologists and social scientists to blame the restraints on sexual expression. The Prince includes a quote from a student interrogating his own insights:

“I guess we all got restless. We wanted something, but we either didn’t know what it was or were ashamed to put it in so many words. So we went out and made trouble and destroyed property, and only then did we make a bee-line for the girls’ dormitories.

Looking back on it, I can see that that was what we really wanted to do in the first place but because we live in a hypocritical society, we were ashamed to admit it. … The riot gave us an ‘out’. It allowed us to kid ourselves that the panty raid was just an afterthought.”

The magazine writer continues: “Who can say whether a man will be the better for having endured four or more years of virtual celibacy, or the worse? And who can say whether it is better to have a riot or a panty raid now and then than to indulge in premarital sex?”

My other favorite document is a handwritten to-do list, specifically a list of phone calls that the university’s president needed to make the morning after the riot. First item: “mothers of incoming freshmen.”

A few years earlier, it had been possible for a Princeton administrator to quell a riot by standing on a car bumper and telling the kids to go home, at which point they would sing, “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow.” But by 1963—the year sexual intercourse began, or was at any rate supposed to have begun—the campus was the perfect tinderbox, and not for nothing media catnip, thanks to such Ivy League-romancers as Fitzgerald, John O’Hara, and the original spring-break coming-of-age story, 1960’s Where the Boys Are. The heat of the political riots of 1964 Berkeley was first felt at a country-club bonfire. Ironically or not, the Establishment hooligans of Princeton, Yale, and Brown were canaries in the coal mine of the counterculture, and they initiated a certain tradition of campus dissent.

Testing the limits of tolerance, the Spring Riot proved the limits of the panty raid. Such carnival events sometimes came to college towns for years after, most with the mere tone of child’s play, but it was doomed. Some of the kids got interested in protests that had politics as their cause (or their fig leaf), and some of the girls stopped wearing bras, and a lot of people began to recognize how easily a minor prank could escalate into a freelance mass-psychology experiment requiring the attention of both Walter Cronkite and the National Guard. Obviously, the panty raid is dead and buried. In the age of the Take Back the Night March, it is incorrect. In a world where “Thong Song” is an oldie, it is superfluous. Coeds became women, and joined the boys in innovating new strains of misbehavior: “Newsflash, you stupid cocks: FRATS DON’T LIKE BORING SORORITIES.” The boys convicted of riotous behavior in the spring of ’63 were in the wrong place at the wrong time, minor accomplices to the culture’s murder of innocence.