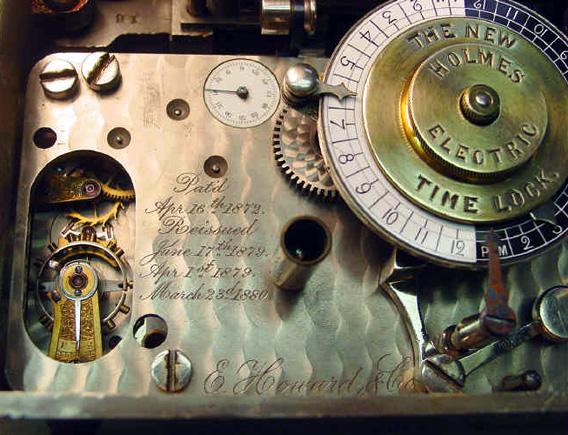

It would be roughly accurate to say that there have been locks as long as there have been things humans wanted to guard. Locks figure in the Bible (“And the key of the house of David I will lay upon his shoulder”), and in Homer. The pin tumbler lock, a technology popularized by Linus Yale Jr., dates more than 4,000 years ago to Egypt, where, as Scientific American observed in 1899, it “can still be seen in any of the older streets in Cairo.” England issued its first lock patent in 1774, the United States in 1790. With the Industrial Revolution came a flurry of activity, new wealth to guard. The bank vaults of the 19th century, sporting names like the “Magic Infallible Bank Lock,” were ornate portals to the monumental caches they secured, bristling with features; there were locks that occluded the key as it entered (to prevent revealing its shape to nearby onlookers), locks that fired bullets or tear gas canisters if opened improperly. In the early 1870s, banks began to equip their vaults with “time locks,” set to be opened only on Monday morning.

John Erroll is the curator of the Mossman Collection, an impressive, if little visited, assortment of locks housed in a small room in New York City’s General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen. As we tour the display cases, Erroll tells me that time locks emerged in response to a series of masked robberies, in which armed gunmen would roust bank managers from their beds at home on the weekend, march them to the bank, and force them to open the vault. “After the Civil War, there was a certain kind of violent atmosphere in the U.S.,” he said. “All these young men came back from the war, young men out of work, and they went into the bank-robbing business.” One of the most curious locks Erroll showed me, “Wooley’s Fluid Time Lock” (patented in 1877), used water for its time-keeping mechanism. “One difficulty with water,” Erroll noted, “is that it doesn’t really drip at a constant rate.”

Photo courtesy of Mark Frank

A few days later, I drove to Long Branch, N.J., to visit Ed Roskelly, who I had met at the Dutch lock-picking conference LockCon. His locksmith’s shop, Bullet Lock, is located on Broadway in an old men’s clothing store. Roskelly, who as it turned out had installed the locks guarding the locks at the Mossman Collection, is an enthusiastic lock collector, and he walked me through his holdings: ancient, ornate warded keys (which, despite their complex appearance, were rather easy to pick); medieval lady’s rings that were themselves keys to small chests; stout Nuremberg iron strong boxes; wooden locks from Africa; and trick Turkish locks in which a series of keys open a successive chain of keyholes. A poster of Houdini (“Europe’s Eclipsing Sensation”) was on one wall; a poster of Louis XVI on another. “He was supposed to be a great locksmith,” Roskelly said. “Before they cut his head off.”

For all the rich history in the shop, the modern locksmithing business is rather less exotic (even if Roskelly has done the security for the homes of some of the Garden State’s better known musical performers). Behind the front counter, he shows me a collection of thousands of key “blanks”—the raw material of duplicating keys—noting, however, that most of the 200-some keys he cuts in a week come from a handful of brands like Schlage and Kwikset. (Many keys for high-security locks, like Medeco, cannot be openly displayed, as a wannabe picker could examine them for telltale grooves and the like.)

Another large part of the locksmith trade is what are called “lockouts”—or someone losing their keys. “I’ve got a guy out right now opening a safe,” he says. “The lady lost the combination.” And while I envisioned a safe technician, crouching in front of a dial, stethoscope in his ears, the reality is more prosaic. “We’re never going to make a living picking a lock,” he says. While he has sent his employees on safe manipulation courses, he says they are allowed “maybe five minutes” to pick a lock. “If you can’t pick it in five minutes, get the drill, drill it out, and put a new lock in.”

In fact, drilling has long been the preferred criminal method of entry. Why pick a lock when you can obliterate one, or, as Roskelly demonstrated, with a small safe, simply peel back the metal sides and chip away at the concrete inside. “You have to keep in mind,” Wels had told me, “the lock is a rather fragile thing.” The most common burglary method in the Netherlands, he told me, is the “Bulgarian method,” named for a technique employed by criminal gangs from that country which involves simply using a pliers on a weak spot of the lock to wrench it free, then opening the door with a screwdriver.

Actual skilled lock-picking is an elusive creature in the wild. One afternoon at LockCon, I had walked to Gamma, a Dutch home improvement store, with Datagram and Schuyler Towne (editor of NDE—or “non-destructive entry”—magazine), to buy some tools for the impressioning championships. Datagram, a longtime computer security consultant, has recently begun working in the field of forensic locksmithing. He is occasionally called in to crime scenes to determine not only a means of entry, but whether the lock-picking itself was authentic or merely insurance fraud. “There’s the obvious stuff, people just run a screwdriver across the face of the lock and say, ‘It was picked,’ ” he said. “Or what happens is they’ll leave marks on half the components of the lock. But you can’t pick a lock by manipulating half the components.” We paused by a soda vending machine, where he intently fingered a series of buttons. “Free soda?” I asked. “No, but sometimes you get the debug code.”

Photo courtesy of AB Security Group, Inc.

There are some lock pickers in the real world. A few weeks after LockCon, I met with Peter Field, of Medeco, in New York City. In the late 1960s, he said, police were noting a high number of burglaries with no signs of forced entries. “There were a lot of pin tumblers that had been around for years, there was no key control”—that is, there were a lot of duplicate keys floating around. Medeco, he said, was founded on a simple idea: “Pin tumbler locks move up and down. Medeco moves up and down and rotates. It moves in three dimensions rather than two dimensions. Tumblers read the elevation, while sidebars read the rotation.” It is something akin to the modern tamper-resistant caps on pill bottles, where one must both squeeze and rotate at once. But, as Field notes, a few years later a locksmith made a “decoding” tool that opened the lock; Medeco made a change so it wouldn’t work—and the pattern repeats. A few years ago, a lock hobbyist named Jon King created a new decoding device, exploiting a new weakness. “Jon has a very good kinesthetic sense,” says Field. “I’ve only known another man like him, and he was an expert on picking lever locks.” And so it goes, with the lock company adding new types of pins, “false grooves,” sidebars—any number of tweaks to reduce feedback to the picker or throw him off the trail.

What you are buying, in essence, is time. This is how locks are rated, by agencies like the Underwriters Laboratory: How long will it be able to withstand a variety of attacks. “I have always been happy to acknowledge any lock can be compromised,” Field said. “It’s just how much effort is someone going to take.”

“Anyone who says they have a lock that can never be picked is fooling themselves,” he continued. “There will be a compromise of some sort.” I was unsettled to hear this from a maker of locks, and I wanted to press him: But what about the perfect lock? What if money were no object? But I began to see I was on the wrong track. “Why would you want this elaborate thing when you’ve got windows on the first floor? People would smash windows and come in,” he said. “All you want is something that will show you a sign of forced entry. You want to protect things. If someone does break in you’ve got the insurance—that’s part of your risk management.”

The words “forced entry” speak to a crucial distinction in the lock world. For the most part, sophisticated lock picking does not flourish in criminal circles, either for lack of knowledge, or because it is simply not worth the time compared to an expedient brute force attack. But as I learned at LockCon, there are those for whom lock picking is not merely a means to gain entry, but a concealing move as well: a way to hide the fact that they were there. One night, late into the conference, after many rounds of beer and air hockey, a murmur ran through the halls. There was, it was announced, an unscheduled “secret session” that would be taking place, in a conference room upstairs, at around 11 p.m. When I joined the crowded room, Wels was asking that participants put away cellphones and cameras; anyone not complying would be asked to leave. A man got up, launched a PowerPoint, and began to talk about a “special tool” he had briefly had access to, which essentially would allow “untrained field agents” to read the inner details of a lock, and make a key. These high-end tools, crafted by a handful of people in the world, are made with one specific lock in mind, costing upward of $10,000. They are bought by, it is widely understood, intelligence agencies wishing to gain surreptitious, and presumably undetected, entry. Given the small contours of this world, I was sternly warned that any further information I were to give, about where the man came from or about the tool itself could result in his losing his job. And here was a curious twist on the notion of security by obscurity: This group of lock obsessives wanted access to this tool for themselves, but did not want the disclosure to travel further. As Wels said, “I want to know if the government can get in my place.”

The lock is both symbol and act of our security. That security may be broadly defined; Freudian psychoanalysis suggested that in dreams, keys were phallic symbols, locks the “unexplored vagina.” But locks, merely by having an opening, by needing to admit that key, are inherently vulnerable. The mechanical tolerances necessary to allow the key to function over time are themselves a weakness. The key itself, with each swipe in and out, each minor scraping of metal, contributes to that vulnerability; “as the lock wears,” Roskelly told me, “you’re almost picking the lock” as you open it with a key. And what, in the end, is the purpose of locking up all those secrets behind sophisticated locks if, as in the case of WikiLeaks, the greatest security lapse of our age, the documents in question left the premises on a thumb drive?

Still, these weaknesses do not keep people like Wels from imagining, almost desiring, the perfect lock. “At the end of the day, the perfect lock is a combination of electronic and mechanics,” Wels told me. “It will be open source; I don’t believe in a black box. Only if enough clever people look at it can it be considered secure.” Then he broached what seemed like an apostasy. “The perfect lock may not be a lock at all. It may a door with no lock in it at all, with some part in the frame, behind a steel plate, remote controlled.” But then that lock too would only be as secure as those who used it.