This week I spoke to about 500 presidents, faculty, and administrators at the National Association of Community Colleges and Entrepreneurship in Charlotte, N.C. They wanted to talk about the changing landscape of higher education: decreased public funding, increased demand, private sector speculation. In many ways, those changes came first for the community college system. Conceived during the height of the middle-class expansion in the 1960s, the community college sector represented an ambitious public investment in universal college access. Today, powerful entities like the Gates Foundation envision community colleges as ground zero for cheaply, efficiently retraining America’s workforce.

Managing dropouts and completions is key to that vision, because community colleges are notorious—somewhat unfairly so—for their dropout rates. As Jon Marcus wrote in the Hechinger Report in August, though the U.S. Department of Education puts the official community college graduation rate at 18 percent, that number rises to around 40 percent if you count the 1 in 4 community college students who transfers to a four-year institution and graduates. Without context, these statistics undermine the community college mission.

Putting aside famous dropouts like Gates, Jobs, and Zuckerberg, to drop out of college is seen as evidence of failure, of untapped human capital, of structural inequality. But failure is actually one of the greatest strengths of our higher education system. In no other country can a student fail so often, so spectacularly, with such a low penalty. Especially for nontraditional students, failure may be underrated.

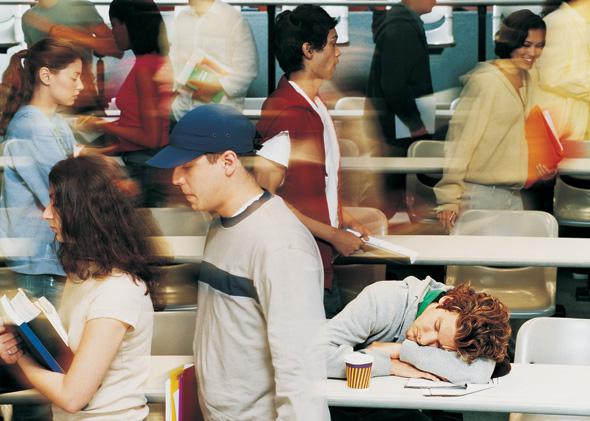

What a lot of community college students are doing is what education researchers call “swirling.” As Jeffrey Selingo recently wrote in the Chronicle of Higher Education, more and more students “attend multiple institutions—sometimes at the same time—extend the time to graduation by taking off time between semesters, mix learning experiences like co-op programs or internships with traditional courses, and sign up for classes from alternative providers such as Coursera or edX.” While Selingo focuses on traditional co-eds who swirl as a lifestyle choice, there is another group for whom swirling is a necessity of life. The demographic future of higher education is older, browner, and full of students who are also parents, workers, and caretakers. They are exactly the kinds of underserved students that community colleges were designed to accommodate, while also serving the workforce needs of local communities. When these students swirl in and out of higher education, it’s often because of the conditions that made them community college students to begin with. A parent’s child care needs may change. A worker retraining for a new field gets a job before they finish a program. A poor student takes on some extra shifts to make ends meet.

For a lot of reasons, we really want people to graduate these days. Degrees are an easy-to-agree-upon metric for researchers. They bring greater economic returns than just some college without a degree. When Barack Obama proposed regaining the mantle of the world’s most educated population, he talked about certificates and degrees and not learning. A good school, by definition, would get students to graduation.

One of my fellow speakers at the NACCE event pointed toward the complexity of this conflation. Accepting NACCE’s Lifetime Achievement award, venture capitalist and philanthropist Gururaj Deshpande of MIT pointed out that community colleges are unique to the United States. In India, Deshpande said, the focus is on high-stakes tests that unilaterally consign students either to the educated class or the working class. The system “had so narrowly focused learning on testing,” he said, “that memorization had replaced learning.” In other nations, entrance exams are the single point of entry to higher ed, so students work really hard—for example, in South Korea, where hagwons—private cram schools—make up a billion-dollar industry and one top tutor makes $4 million a year, as Amanda Ripley reported in the Wall Street Journal.

When you’ve only got one shot at college, there’s a lot of motivation for you to get it right. In the U.S. we’ve got lots of shots. Nation-to-nation comparisons of lazy U.S. students to hardworking students in East Asia often obscure this difference. In the U.S., you can fail out of high school, take the GED, dabble in a few community college classes, eventually transfer to a state university, graduate, and go on to get a medical degree or a Ph.D. It’s not the normal course for drop-outs, sure, but it is possible. And it’s the possibility—represented by a network of accessible, affordable community colleges that serve students who can’t move or stop life to go to a traditional college straight through—that has made ours a pretty good system. When one can fail, and failure does not doom one’s life chances, we all benefit. When we consider that inequality is largely a generational transfer from poor parents to their children, more opportunities for the vulnerable to take a risk on education can only be a good thing.

James Mellow, a hairdresser in Davis, Calif., recently told me how upset he was to hear that City College of San Francisco was facing closure. Back when Mellow was a couch-surfing young man in an expensive city, SFCC “was the kind of place you went to plug into a community or do something useful with your time while you looked for work,” he said. “Tuition was so cheap that it was more expensive not to take a class than to enroll.” Those are the kinds of daily risk calculations that need to tilt in favor of college enrollment. But betting on an expensive for-profit college is significantly riskier if the opportunity loads up so much debt that it effectively prevents you from ever re-enrolling in college—then you only have one shot. Similarly, a narrow focus on degree completions stifles the mission of community colleges to provide more access points for students who too often have to choose between managing their life and continuous enrollment. We need to recalculate the price we put on failure, and acknowledge that the freedom to drop out—and drop in—is one of our system’s most significant attributes.