Ku? Poa? Buena onda?

What cool looks like around the world.

What Cool Looks Like Around the World

In America we have at least a passing idea of what's "cool" to us today, even if a singular definition is forever eluding us. But what does it look like in other corners of the world? As with all discussions of cool, this does not attempt to be a comprehensive or conclusive definition of coolness-but rather a snapshot of the concept as perceived outside of the U.S. So here's to being ku, buena onda, or poa—and remember that no matter what anyone else may say, cool can be found pretty much anywhere.

Feiyue. GOU YIGE/AFP/Getty Images

Ku in China

A recent study on China's "Red Cool" by TBWA/China, an international ad agency, found that "zheng neng liang" (meaning "positive energy") is a popular notion among Chinese youth today. TBWA/China's research suggests that being positive and aspirational are considered cool traits among youth. "Real 'cool' is to bring [your] dreams to reality and make them perfect," one young adult explains in the study. "No one should compromise on the way to realizing a dream."

To a perhaps unsurprising extent, in China the monoculture still exists, so being different is often not seen as ku. The things that are cool—or at least highly consumed—include Starbucks ("an indication that they've reached a certain status," says Shaun Rein, managing director of China Market Research Group) and Adidas' NEO line. On the home front, Rein reports that the Chinese-made JDB, an herbal tea, outsells Coke and Pepsi in many parts of the country whileFeiyue shoes have been a hit for hip urban types. The iPhone isn't cool, apparently; Apple's phone has lost sway with mainstream Chinese consumers as of late. (This may in part have to do with there being only eight store locations in the entire country, according to Rein.)

Interestingly, Chinese coolness is heavily influenced by South Korea: It can be found in nearly every form of Chinese consumerism—movies, TV, fashion, and especially pop music. Long before Psy introduced K-pop to the Western world, South Korean culture was dominant across Asia, thanks to Korea's realization that it could find success by exporting culture and investing millions of dollars in arts and entertainment.

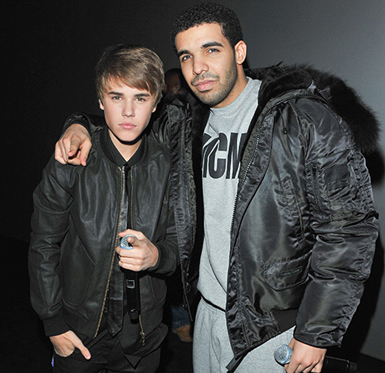

Justin Bieber and Drake. George Pimentel/WireImage

Cool in Canada

Despite Drake's best efforts, Canada has rarely been seen as cool; it ranked fourth in a 2011 poll of the least-cool nationalities (just slightly cooler than Belgians, Poles, and Turks). In fact, Canadians revel in their perceived out-of-touch-ness: "Canada might not be one of the coolest countries in the world but it is one of the most civilized," said Lloyd Price, at the time the marketing director of social-networking site Badoo, in response to the poll results. "Like the Queen, Canada is so uncool, it's cool. And proud of it."

In fact, cool in Canada has less to do with brands, rebellious teenagers, and subversive countercultures, and more to do with altruism. In a study published in 2012, researchers found that their predominantly female sample of "mostly educated" young Canadians associated "friendliness" most often with characteristics of coolness. ("Personal competence" and the more expected "trendiness" followed closely behind.)

Also consider the finalists in a recent " Canada is Cool" photo contest sponsored by the Embassy of Canada in Belgium: "Canada is cool, because I love the way people live with each other and how Canadians respect the wildlife and there (sic) habitat!" reads one caption. And another: "I think this photograph represents Canada as a whole: love, friendship, sunshine (in the figurative sense)." In Canada, it's hip to be square.

Takashi Murakami. Wikimedia Commons

Sugoi in Japan

Once upon a time, Japanese cool was a masculine quality—studiousness was prized, and warriors were lionized. But as noted by scholars Christine R. Yano , Tomoyuki Sugiyama, and others, "cuteness," or kawaii, has taken center stage in Japan, as seen in the global success of Hello Kitty, as well as J-Pop and the trendy, youth-oriented Tokyo district Harajuku.

Yet while the emergence of the aforementioned adorable cat, along with manga comics, anime, and the influential superflat art movement have Japanese roots, there is still some sense that Western influence must be present in order for Japanese exports to be considered cool. In 2002 Doug McGray coined the country's creative efforts as " Japan's gross national cool" and observed that foreign influence was practically essential to being hip, whether it was culturally accurate or not: A "whiff of American cool" from U.S. imports (like potato salad pizza, he suggests) and a "whiff of Japanese cool" in exports (cream cheese-and-salmon sushi) are an indicator of what can be fashionable in Japan.

Today Japan is one of the most aggressive countries in the world when it comes to cultivating and exporting cool: The Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry spends millions on its "Cool Japan" PR initiative, in order to amplify the nation's "soft power." After some blunders, the METI now believes that in order to be successful, it must look to international influence less, and "use Japanese content to sell Japanese products." It's unclear when that will change, however—for now at least, the "Cool Japan" funding doesn't appear to be going to the people working domestically in poor conditions and for little pay; and some artists find the government's PR initiative to be nothing short of uncool.

Mario Tama/Getty Images

Legal in Brazil

A "feel-good" vibe encompasses nearly every cultural aspect of Brazil, as one native explains. And there are many of them: Because Brazil is made up of such a sprawling, diverse population, what's legal depends on a variety of different tastes and sensibilities. When it comes to music, anything currently popular abroad will likely be hip there, but the country also has its own cool and hugely popular genres: explicit, sexualized "funk" music (dubbed "the sound of the people," as the upper class tends to ignore it) and sertanejo (Brazil's rendition of country music).

In recent years, the " small step battle," in which kids post videos of themselves performing intricate dance steps and then challenge others to come up with something even better, has grown in popularity. And underprivileged kids are also finding a voice through graffiti, which was legalized in Brazil in 2009. And there's always sports: As one Brazilian native tells me, "There's an almost tangible sensation that what's 'cool' in Brazil is whatever's healthier for you." Thus the many ads (and sometimes, song lyrics) that rave about the tropical climate and urge people to participate in physical activity—be it fútbol, hiking, samba dancing, or going to the beach.

TARTU, ESTONIA: Young Estonian boys play footbag (hacky sack) during a winter's night in the main street of Tartu early 07 January 2005. This alternative sport is becoming increasingly popular among Estonia's youth. JANEK SKARZYNSKI/AFP/Getty Images

Cool in Estonia

It's only in recent years that the Baltic states have seen prosperity; after gaining independence in the 1990s, the region was extremely poor, and the cultural notion of "cool" wasn't an issue of concern, as a recent resident of Latvia explains to me. But the economy has since improved, especially in Estonia, and what's hip now is not so different from what's hip in the West.

American and European cultures are very much integrated into the Baltics. Electronic music is still big in underground clubs, and while Estonia has a small indie/alternative scene, native acts generally won't be deemed cool until they've first gained popularity elsewhere. The Swedish-owned retail company H&M just opened its first store in Estonia in September, and Zara is popular as well.

Hipsters also exist, and one Estonian's description of such a person you might see there sounds eerily similar to Brooklyn's typical export: Thin, "highly emotional" young males adorned in skinny jeans and cardigans, perhaps accompanied by a bike. However, while American hipsters tend to be as old as their mid-30s, in Estonia, those in their mid-20s and above tend to ditch the fashion trend.

One thing that separates Estonia from the West is sensibility—while young Americans tend to be extremely conscious of irony (think of the incredibly self-aware hipster mustache), most people in the Baltic region are multilingual, and so shades of meaning can be lost in inter-lingual conversation. Instead, one appears as she wishes to appear to others; if you dress like a hipster, you do so because you simply think it's cool, not to make an ironic statement.

Salman Khan. Wikimedia Commons

Cool in India

Earlier this year, the Times of India posed the evergreen question: " What's cool?" The article featured a curious mix of responses and pull quotes from prominent Indian figures like singer Shefali Alvares and, uh, Taylor Swift. But the most interesting answer came from columnist Palash Krishna Mehrotra: "How can [Indians] be genuinely cool when we are always so eager to please?" he wondered. " 'Coolness' involves doing your own thing without thinking what others will think of you."

Maybe. As a general rule in India, most things connected to Western culture may be considered cool. But there are at least two viewpoints on what's truly hip in India, as one native now living in the U.S. explains to me: the small-town point of view, and the big-city one. With the former, Western culture can be somewhat idolized, as primary exposure to such things is via television; coffee shops (an icon of leisure and prosperity rarely found outside urban communities) and iPhones are admired by younger people. (And Hollywood is cooler than Bollywood.) When it comes time for college, many will seek out the majors that are the most likely to get them jobs in the U.S.

In the city it can be quite different. Young urban people tend to have more money, so their exposure to Western culture often comes from trips abroad. Often, they return to India feeling more appreciative of their own country's culture, or even are more inclined to take vacations and backpacking trips within India itself.

Daniel Craig. Andreas Rentz/WireImage

Brilliant in the U.K.

As one Brit living in the U.S. explains it, "Generally, the British psyche is not to try too hard. Ever. God forbid you're earnest. We don't deal well with that." That's one reason why, when compared with America, high school and college athletes aren't nearly as idolized as they are here, and there's less of a culture built around jocks (and people who want to sleep with jocks). And while there's definitely great national pride for those who domake it big—see the U.K.'s success at the 2012 Olympics—obsessing over sports "would require trying really hard."

Currently, the documentary TV series Educating Yorkshireis having a moment, resonating especially with teenagers. The show, which follows several Yorkshire teens at a troubled school rife with ethnic and class tension, reached more than 4 million people for its premiere last month. And the students at the center of Educating Yorskshire have become celebrities in their own right—one of them, Bailey, who sports hand-drawn eyebrows, has inspired a catchphrase: "D'you like me eyebrows? I shaved 'em all off."

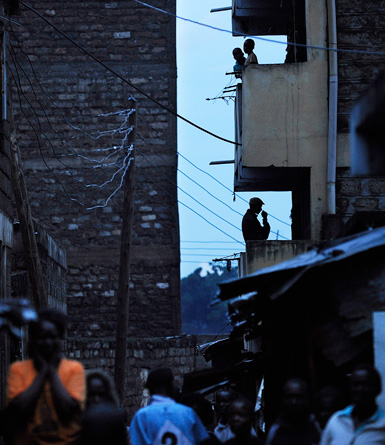

AFP PHOTO/Tony KARUMBA

Poa in Kenya

Sheng, a language combining Swahili and English (along with other Kenyan dialects) that first emerged in Nairobi in the 1970s, has come to dominate the way in which young people in Kenya communicate with one another. What was once a language associated primarily with thugs and Nairobi youth who wished to evade the law and their parents, respectively, has now spread throughout the entire country, appearing in hip-hop as well as literary publications targeted at Kenyans under 30.

One such publication is Shujaaz.fm, a monthly comic book distributed monthly through the Daily Nation. Shujaaz ("heroes" in Sheng), centers on a 19-year-old kid who, unable to find a job after finishing school, creates his own radio show under an alter ego. (The show airs on real FM stations across the country.) The comic educates youth about everything from agriculture to political activism, and though solid numbers are hard to come by, the head of the consultant agency behind the project has claimed that Shujaaz reaches about 5 million Kenyans between 10 and 25 years old monthly.

On a smaller scale, a tiny contingent of Kenyans—an estimated 300 in Nairobi—have adopted their own version of goth culture. Typically adorned in black, tattoos, and piercings, Kenyan goths are often stared at and sometimes ridiculed, as many people perceive them to be violent drug abusers based primarily on their attire. (Many older goths are actually practicing Christians, and many stories of crimes committed by goths are unsubstantiated, according to Think Africa Press.) Because of this, some prefer to don the aesthetic only when within "the safety that comes in numbers."

Young people practice parkour in a tunnel used as a track under one of the busiest highways in Mexico City on 24 May, 2012. The government of the Mexican capital created the free space for young people to practice different sports disciplines with trainers from the Youth's Institute of Mexico city. OMAR TORRES/AFP/GettyImages

Buena onda in Mexico

Much of Mexico's youth culture is characterized by resistance against poor living conditions and difficult police-citizen relationships through cultural expression, especially through music and fashion. As Daniel Hernandez, who chronicled several Mexican subcultures in his book Down and Delirious in Mexico Citywhile living in the nation's capital (where half the population is under 25) for several years, has put it: "It's hard to live here, so that makes good youth culture."

In Condesa, a Mexico City district, to be a hipster is to be "as eclectic as possible" when it comes to personal taste, Hernandez observed in his book. Sartorial display is held in high regard, with young designers creating daring designs and "clothes meant for partying." And unlike Brooklyn's hipsters, most hipster Mexicans don't idealize the struggling artist or craftsman persona, but rather aspire to upper-middle-class life in the likes of Coyoacán or Del Valle.

The punk, goth, and ska movements that emerged in the 1980s still remain (though as Hernandez writes in his book, the youth reject clear-cut terminologies as descriptors of their identity), and the El Chopo marketplace in Mexico City is where all of these groups and others convene on a weekly basis. Here, " the plaza and the family are central, not the individual."

And in Ciudad Juárez—once known for being the " deadliest city in the world"—"nueva ola fronteriza" ("new border wave") has arisen in opposition to the once-popular narcocorrido genre of music, which glorifies drug cartels and violence. The glorified ballads of Los Tigres del Norte and other performers are now considered passé to much of Mexican youth-and nueva ola fronteriza bands like Pájaro Sin Alas (Bird Without Wings), who sing songs with peaceful messages influenced by tropical rhythms and Latin pop genres, are emerging as positive alternatives.

Xander Ferreira and Nick Matthews aka DJ Invisible of the South African band Gazelle (Stocktown)

Befok in South Africa

Today's South African youth are known as the "born free" generation-those born after the end of apartheid and election of Nelson Mandela in 1994. As poet Lebo Mashile-who, while older, is said to be a voice for the born-frees- has explained it: "Being a born-free means that I experience the legacies of apartheid, you know. But it also means that I have access to opportunities."

Because of this, as well as South Africa's status as one of the most unequal countries in the world, youth maintain an especially complex identity. Johannesburg has been a leader in creativity and identity shaping for youth despite the gaping disparities between the very poor and the wealthy, and heavy political unrest; art studios, fashion, and music have thrived in the city in recent years-leading some to compare it to Brooklyn. And there are variants of cool to be found there: Some black youth, for instance, reject the notion of Western stereotypes of African dress, choosing to go for more muted styles; others, like the internationally known Smarteez fashion crew, borrow from both African and Western style unabashedly.

In recent years a backlash has developed against the nation's staunch income inequality. A growing subculture known as izikhothane (Zulu for "to lick," but which has now come to mean "bragging") has created a ritual that involves buying expensive clothing and accessories and destroying the items after using them only once. The youths, most of them poor and/or unemployed, then document their work online. " Destroying symbols of value gives them recognition and status," one Sowetan explained to the Guardian,"and that is what they crave-much more than money. The bigger the display of abundance and your ability to destroy it, the bigger your 'swag,' and that's what matters to them most."