Part 1 of a monthlong series on the history and future of cool.

Last month the electro-psychedelic band MGMT released a video for its “Cool Song No. 2.” It features Michael K. Williams of The Wire as a killer-dealer-lover-healer figure stalking a landscape of vegetation, narcotics labs, rituals, and Caucasians. “What you find shocking, they find amusing,” the singer drones in Syd Barrett-via-Spiritualized mode. The video is loaded with signposts of cool, first among them Williams, who played maybe the coolest TV character of the past decade as the gay Baltimore-drug-world stickup man Omar Little. But would you consider “Cool Song No. 2” genuinely cool, or is it trying too hard? (Is that why it’s called “No. 2”?)

The very question is cruel, of course, and competitive. You can praise the Brooklyn band’s surreal imagination, or you can call it a dull, derivative outfit renting out another artist’s aura to camouflage that it has none of its own. It depends which answer you think makes you cooler.

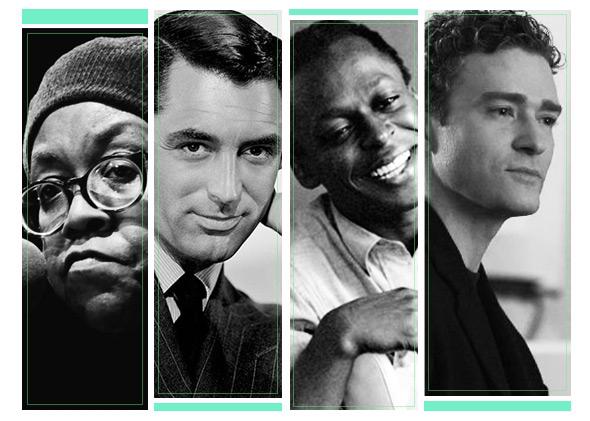

If that sounds cynical, cynicism is difficult to avoid when the subject of cool arises now. Self-conscious indie rockers are easy targets, vulnerable to charges of recycling half-century-old postures that arguably were purloined from African-American culture in the first place. But what is cool in 2013, and why are we still using this term for what scholar Peter Stearns pegged as “a twentieth-century emotional style”? Often credited to sax player Lester Young in the 1940s, the coinage was in general circulation by the mid-1950s, with Miles Davis’s Birth of the Cool and West Side Story’s finger-snapping gang credo “Cool.” You’d be unlikely to use other decades-old slang—groovy or rad or fly—to endorse any current cultural object, at least with a straight face, but somehow cool remains evergreen.

The standard bearers, however, have changed. Once the rebellious stuff of artists, bohemians, outlaws, and (some) movie stars, coolness is now as likely to be attributed to the latest smartphone or app or the lucre they produce: The iconic statement on the matter has to be Justin Timberlake as Sean Parker saying to Jesse Eisenberg as Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network, “A million dollars isn’t cool. You know what’s cool? A billion dollars.” That is, provided you earn it before you’re 30—the tech age has also brought on an extreme-youth cult, epitomized by fashion blogger and Rookie magazine editor Tavi Gevinson, who is a tad less cool now at 17 than she was when she emerged at age 11. What would William S. Burroughs have had to say about that? (Maybe “Just Do It!”)

Cool has come a long way, literally. In a 1973 essay called “An Aesthetic of the Cool,” art historian Robert Farris Thompson traced the concept to the West African Yoruba idea of itutu—a quality of character denoting composure in the face of danger, as well as playfulness, humor, generosity, and conciliation. It was carried to America with slavery and became a code through which to conceal rage and cope with brutality with dignity; it went on to inform the emotional textures of blues, jazz, the Harlem Renaissance, and more, then percolated into the mainstream.

Stearns argues that cool’s imperatives of flexibility and fluidity helped Americans escape rigid Victorian morality into modernity and developed along with mass production and mass media as a new individualist ethos. But most analysts agree it only became widespread after World War II. As Dick Pountain and David Robins wrote in their 2000 book Cool Rules, it “took the collapse of faith in organized religion and the trauma of two world wars to turn it into a mass phenomenon,” one that thrummed with the paranoias of the atomic age and the Cold War as well as fantasies of cross-racial convergence. (See Norman Mailer’s mostly regrettable essay on the “White Negro.”)

Elvis and James Dean introduced cool to Middle America, but it was the Beat movement that revered it most, putting its queer shoulder to the wheel, even as black poet Gwendolyn Brooks was warning that “We Real Cool” was coming to mean “we die soon.” The Beats were succeeded by both the Warhol Factory and ’60s hippie culture, which converted cool to common currency in concert with Madison Avenue. And not just in its crucible, but around the world via pop and consumer culture. As Pountain and Robins claim, “American Cool proved in the end to be more exportable than Soviet Communism.”

That oversimplified history gives some sense of how cool moved from margins to center and became our elastic container for anyone and anything with relevance and spark. To be cool is to have cultural and social capital, and most urgently it is to be not uncool—a hang-up most of us pick up in adolescence that’s damnably hard to shake even if it mellows with age. Cool is an attitude that allows detached assessment, but one that prizes an air of knowingness over specific knowledge. I think that’s why it doesn’t become dated, unlike hotter-running expressions of enthusiasm like groovy or rad. As Stearns says, cool is “an emotional mantle, sheltering the whole personality from embarrassing excess. … Using the word is part of the process of conveying the right impression.”

This is part of what makes it so easy to appropriate, to market, and even to manufacture, in a process that’s grown ever more rapid—nothing wants to be cooler today than a corporation, and digital media erase the need to wait for lifestyle and aesthetic innovations to make their way from the outré to the mainstream. As critic John Leland has put it, “In a society run on information, hip is all there is.”

That’s the trouble with trying to point to cool’s center today. It is everywhere and nowhere. It is noise-music cassettes and K-pop, adult male My Little Pony fans and Maker Faires, alternative comedy podcasts and Holy Hip Hop, the feminist Twittersphere and even creepy pickup artistry, depending who you are, and most of all it is being coolly aware of all of the above. Mind you, most claims about a new balkanization of taste are nearsighted: Contrary to sentimental legend there never was a pop “monoculture.” So the issue now is not so much cool’s fracturing as its evanescence: Cool is what’s on BuzzFeed or Reddit in the morning, but it’s not cool by end of the day. The more ephemeral, the cooler; Snapchat is cooler than Instagram, which is cooler than Twitter, which is cooler than Facebook, which is cooler than the Web, which is infinitely cooler than print.

As a result, today’s celebrities, by definition overexposed, seldom can hold on to any 20th-century-like appearance of cool. Kanye West’s endurance as a superstar is owing to the fact that cool was never exactly what he brought to the table—he has more in common with the revenge-of-the-nerds, hip-to-be-square tide that’s elevated the tech geeks. Beyoncé is an old-fashioned showbiz gal under the surface, while her 1990s-holdover husband vacillates unattractively between flirting with avant-garde artists and flaunting ever-more-venal materialism. Anonymity and disappearing acts (cf., Daft Punk or Earl Sweatshirt) can be effective gambits to extend a bit of mystique past fruit-fly timelines.

Jennifer Lawrence arguably has attained “it girl” status partly through displays of uncoolness (the Oscar-steps stumble, the zany motormouth, the gormlessness when encountering her acting heroes) that only set her actual suaveness as an actress in a more flattering light. In another register, Lady Gaga and now Miley Cyrus push themselves beyond fashionable eccentricity into the deliberately grotesque. Lena Dunham shoots herself in awkward nudity on Girls in part to knock herself off any possible pedestal. This pattern prevails even among fictional characters—the anti-heroes in 21st-century serial “quality” drama aren’t chill Eastwood or Brando types but panic-attack-prone Tony Soprano, or Walter White, whose scheming intellect is undone by his pedantic-nebbish emotional insecurity. The likes of Omar are the exceptions that prove the (white) rule.

High-profile uncoolness comes as a relief to today’s audiences, I believe, because the stakes of cool for so many of us have become disastrously high. “Knowledge work,” the main alternative to subsistence-level service jobs, demands a performance of knowingness, and the transitory instability of employment requires everyone to operate as free agents marketing our own “personal brands.” In this situation—the deregulation of everything (except pot, so it remains universally hip) and the disorganization of the labor market—coolness becomes all but mandatory, even as we break into a sweat.

For a wired generation, cool’s markers aren’t tough to acquire, but maintaining them can become a frantic preoccupation. Young aspirants in cultural fields often come off to me as fairly confident that they are cool and profoundly unsettled about whether they’ll get to be anything more. The much-maligned hipsters (a cultural bogeyman I’ve avoided mentioning till now) expand that syndrome to a parodic, near-pornographic level—their apparent overidentification with the laws of cultural capital and embodying rootless mobility exposes, consciously or unconsciously, the unspoken edicts of post-industrial cool apathy, as if to say, “All the emperor has are clothes.”

Is coolness a trap, then, a nightmare from which we need to awake? Compared to the scale of the world’s real problems, it’s a frivolous, even malignant distraction, a cul-de-sac of endless and servile adolescence. Yet once it shielded African-American culture and pried open space for Jewish, gay, and other repressed perspectives. How then does it shift when the president of the United States, a conspicuously cool customer, is black and advocates gay marriage, and when black artists (rather than white imitators, though those still abound) tend to dominate the pop charts? The post-racial society is a myth, but perhaps it is a myth of cool—the one that spurs, for instance, MGMT to cast Williams as a shaman-assassin, or Vice magazine to dabble in hipster racism, or kids at electronic music festivals to dress up in faux Native American headdresses and face paint as clueless “tribal chic” even in front of a real live Native American music group that condemns it as “redface.”

So, just as the camp aesthetic inevitably has been diluted by queer mainstreaming, maybe cool is finished as a distinct category and is now just a generic hook on which to hang hierarchy. And yet … I owe cool too much (e.g., Krazy Kat, Gertrude Stein, Thelonious Monk, Frank O’Hara, Agnes Varda, The Slits, Outkast, David Foster Wallace [despite his protests], etc., etc.) to give up willingly on its legacy of canny, impassioned skepticism and its capacity to slip the strictures of propriety and social segregation. It’s not like we’ve run out of boundaries that want crossing: What about, say, the ones that drew the rules of cool with minimal input from women, non-city dwellers, or non-Westerners? Perhaps some elegant sidestep remains around the present sensation of being hornswoggled into a symbolic-status Hunger Games in which the scramble for cred is a top-down bloodbath of “creative destruction.”

Yeah, man, that’d be coolsville.