One recent evening, I celebrated my birthday in the outdoor courtyard of a bar. As the night wore on, and friends fell by the wayside, each departure occasioned a small ritual. A pal would sidle up to whichever conversational circle I was in; edge closer and closer, so as to make herself increasingly conspicuous; and finally smile, apologetically, when the conversation halted so I could turn to her and say goodbye.

Nothing but good intentions here. To some small extent, I appreciated the politeness of this parting gesture. It was not a major imposition to pause for a moment and thank folks for coming.

But there’s a better way. One that saves time and agita, acknowledges clear-eyed realities, and keeps the social machine humming.

Just ghost.

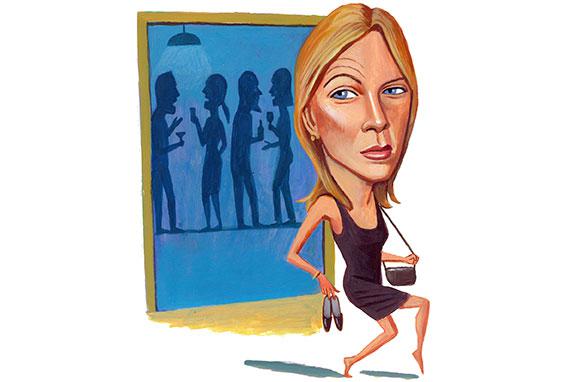

Ghosting—aka the Irish goodbye, the French exit, and any number of other vaguely ethnophobic terms—refers to leaving a social gathering without saying your farewells. One moment you’re at the bar, or the house party, or the Sunday morning wedding brunch. The next moment you’re gone. In the manner of a ghost. “Where’d he go?” your friends might wonder. But—and this is key—they probably won’t even notice that you’ve left.

Yes, I know. You’re going to tell me it’s rude to leave without saying goodbye. This moral judgment is implicit in the culturally derogatory nicknames ghosting has been burdened with over the centuries. The English have been calling it French leave since 1751, while the French have been referring to filer à l’anglaise since at least the late 1800s. As with other cross-Channel insults—depending on your side, a condom is either a French letter or la capote anglaise, syphilis the French disease or la maladie anglaise—the idea is to pin unsavory behavior on your foes.

Here in the U.S., the most-used term seems to be Irish goodbye, which, due to unfortunate historical stereotyping, hints that the vanished person was too tipsy to manage a proper denouement. Dutch leave is a less common, but apparently real, variant. (I picture someone taking a couple pulls on a vaporizer, scarfing too much bitterballen, and stumbling into the night.) And then there’s the old, presumably Jewish joke: WASPs leave and don’t say goodbye, Jews say goodbye and don’t leave.

But religio-nationalist slurs aside, is it really so bad to bounce without fanfare?

We all agree it’s fun to say hello. A hello has the bright promise of a beginning. It’s the perfect occasion to express your genuine pleasure at a friend’s arrival. But who among us enjoys saying goodbye? None among us! Not those leaving, and not those left behind.

Goodbyes are, by their very nature, at least a mild bummer. They represent the waning of an evening or event. By the time we get to them, we’re often tired, drunk, or both. The short-timer just wants to go home to bed, while the night owl would prefer not to acknowledge the growing lateness of the hour. These sorts of goodbyes inevitably devolve into awkward small talk that lasts too long and then peters out. We vow vaguely to meet again, then linger for a moment, thinking of something else we might say before the whole exchange fizzles and we shuffle apart. Repeat this several times, at a social outing delightfully filled with your acquaintances, and it starts to sap a not inconsiderable portion of that delight.

Let’s free ourselves from this meaningless, uncomfortable, good time–dampening kabuki. People are thrilled that you showed up, but no one really cares that you’re leaving. Granted, it might be aggressive to ghost a gathering of fewer than 10. And ghosting a group of two or three is not so much ghosting as ditching. But if the party includes more than 15 or 20 attendees, there’s a decent chance none will notice that you’re gone, at least not right away. (It may be too late for them to cancel that pickleback shot they ordered for you, but, hey, that’s on them.) If there’s a guest of honor, as at a birthday party, I promise you that person is long ago air-kissed out. Just ghost.

Still think it’s an etiquette breach? Simply replace your awkward goodbye with a heartfelt email sent the following morning. This note can double as a formal thank you to the host—a rare gesture these days, and one that actually does have value. (You can even include the link to that English Beat video you couldn’t stop raving about last night.) Got a safety concern, and want to alert people that you’re stepping out alone into the dangerous night? Send a text after you’re out the door.

Once you’ve mastered the basics, you might try out some ghosting variations. I have a friend who favors the “Northern Irish goodbye.” You announce your intention to ghost long in advance, as a warning, so there will be no collateral damage.

Whichever version you choose, it is time to commence ghosting, America. Should you have questions about all this, I’m happy to answer them. I’m just gonna wander toward the front of the bar for a second. Be right back.