If your ancestors could see you today, they might not recognize you as entirely human. Over the past century, medical and technological innovations have made us stronger, faster, smarter—often in ways we no longer notice. Artificial enhancement of the human body isn’t just for cyborgs; most of us have bodies that have already been enhanced beyond their natural potential. To us, these advantages are a routine part of modern existence. To our grandparents, they would have made us seem like Superman. Below are five of the top modern innovations that make us stronger, more fertile, able to shape-shift, and more—and that we take entirely for granted.

Plastic Surgery

Plastic surgery was created by surgeons during World War I to reconstruct soldiers’ faces that had been brutally disfigured by the new weapons of warfare. Bombs, flamethrowers, and crash-prone airplanes scorched swathes of skin and shattered jaws, while trench warfare left soldiers’ heads and necks vulnerable to whizzing bullets. War doctors recognized that saving these men’s lives wasn’t quite enough; as one surgeon noted, “What is the use of life if [a soldier] is not in a condition to seek and to earn a livelihood?” Facial restoration was viewed as a necessity rather than a vain indulgence, and generals, hoping to raise troop morale, heartily endorsed the practice.

After the war, most French and British doctors quit plastic surgery and returned to normal practice. But American surgeons smelled a new market. They set their sights on civilians—particularly women. To legitimize the field and counter criticisms that they were serving only vanity, plastic surgeons cited the practice’s initial medical necessity. Plastic surgery procedures became public spectacles, performed in front of an audience to emphasize their ease and speed. In 1923, vaudeville actress Fanny Brice received a rhinoplasty from a traveling surgeon in her apartment at the New York Ritz in front of a crowd. (The surgeon’s license was later revoked, and Time labeled him “the King of Quacks.”) The procedures became safer and relatively routine, and Americans, particularly American women, were suddenly able to nip and tuck their way to an ethnically bland, generically pretty face.

These days, whatever stigma once surrounded plastic surgery has largely evaporated (in the United States, that is), and the practice remains hugely popular. In 2012, 14.6 million cosmetic procedures were performed, a 98 percent increase since 2000. More than 6 million people received Botox injections, a number greater than the population of Maryland. For several thousand dollars, you can now dramatically alter your body to look pretty much however you want it to. What began as a desperate measure for disfigured soldiers is now a routine procedure for anybody in want of a self-confidence pick-me-up. According to some scientists, that jump—in which a new technology evolves from life-saving to life-enhancing—may simply be inevitable.

The Pill

Humans have long grasped the relationship between vaginal intercourse and reproduction. For about as long, we’ve been trying to sever it. Ancient Mesopotamians, Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans all used balms and herbs to attempt to halt fertilization before anyone fully understood how the process worked. Beginning in the 1500s, condoms became increasingly popular around the world, including in China and Italy. But the prophylactics presented a problem for women: Condoms kept contraception under the control of men.

Contraception was a feminist issue from the start. Margaret Sanger, founder of the American Birth Control League and first president of Planned Parenthood, popularized diaphragms, which helped resolve this disparity. But she and other women’s advocates long hoped for an oral contraceptive for women. The solution would be doubly useful: It separated contraception and sex—with no pause to put on a condom or insert a diaphragm—and it placed women squarely in control of their own bodies. In the early 1950s, scientists developed synthetic progesterone in pill form. The hormone works in three ways: It hinders sperm from reaching the egg, keeps any fertilized egg from implanting in the uterus, and prevents ovulation. In trials, patients were placed on a now-familiar four-week schedule: three weeks on the pill, one week on placebo. This allowed women to continue menstruating once a month, a scheme designed to make the pill seem “natural,” analogous to the rhythm method and thus perhaps acceptable to the Catholic church.

The church didn’t buy it—but American women did. In 1960, the drug company G. D. Searle secured FDA approval to market synthetic progesterone as an oral contraceptive, and by 1963, 2.3 million women were on the pill. In 1965, the Supreme Court overturned bans on birth control for married couples, finding a right to privacy in the “penumbras” and “emanations” of the Bill of Rights. The right to use birth control was extended to unmarried couples in 1972, by which point nearly 10 million women were on the pill. More than 80 percent of women in the United States have used the pill, a proportion that has remained largely steady for the past several decades. And while the pill is not without controversy, it remains a widely used and generally accepted method of contraception. After a multi-millennia quest that has involved solutions as creative as honey and crocodile dung, humans can now separate sex and reproduction with a single pill.

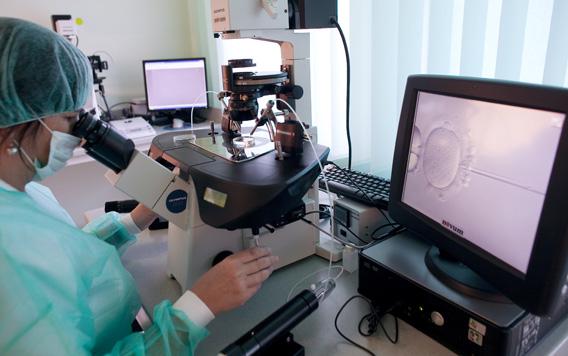

In Vitro Fertilization

What if a couple wants sex to lead to reproduction—and can’t make it happen? Not to worry: Lab technicians can jump-start the reproduction part for you. The process of in vitro fertilization is fairly simple: A woman takes fertility drugs, which stimulate the ovaries to produce a multitude of eggs (rather than the usual one per cycle). Doctors use a hollow needle to suck up the eggs, which are placed in a Petri dish with sperm and become fertilized. In cases of low sperm count or motility, sperm may be injected into the eggs. The embryos are transferred into the uterus, and the pregnancy proceeds as usual. The basic IVF process results in pregnancy about 20 to 25 percent of the time, and each cycle costs around $12,000. Frugal families might consider bringing their funniest friend along for the procedure—patients who laughed following embryo implantation had a 16 percent higher chance of conceiving.

IVF is a curious development in human biological history. The entire purpose of sex, evolutionarily, is to reproduce. (That’s also the entire evolutionary purpose of life.) Natural selection dictated the structure of our genitals (as well as the genitalia of every sexually reproducing species). Heterosexual women may be more attracted to men with large penises, which may be more likely to deposit semen deep in the vagina and thus improve the odds of fertilization. Larger penises may also help displace rival mates’ semen, an evolutionary bonus.

But IVF has the potential to make standard vaginal intercourse an obsolete mode of reproduction. The first successful IVF conception occurred in 1978; in 2011, more than 163,000 IVF cycles were performed in the United States alone. That’s a startlingly rapid development for a technology that allows people to reproduce without intercourse. Eighty years ago, the notion of humans reproducing through artificial means was fodder for dystopian nightmares. Now it’s the subject of romantic comedies.

Aspirin

Pain has plagued animals ever since evolution bestowed nervous systems unto metazoans. But only humans are creative enough to conquer our own bodily suffering. Ancient cultures viewed pain as punishment from the gods and tried to relieve it through animal sacrifice. (In a sense, we’ve come full circle.) Hippocrates sought to alleviate pain by drilling a hole in his patient’s head, inadvertently violating his own oath. Greeks and Egyptians shocked sick people with electric eels, while medieval and Renaissance-era doctors prescribed unicorn horns as cures for the plague and other maladies. (Standard dose: 60 grains.)

One medicine among these peculiar cures, however, did prove effective: willow. The tree, whose healing power was first noted by ancient Egyptians in the Ebers Papyrus, contains salicylate, a primary component of aspirin. Other cultures, including the Greeks, noted willow’s tonic effects, but not until the late 1890s did the Bayer drug and dye company combine salicylate with other ingredients to create aspirin. The anguish of World War I and the Spanish flu brought Bayer massive profits, and aspirin quickly eclipsed in popularity the era’s other popular analgesic: heroin.

Our ability to synthesize various ingredients to reduce pain isn’t an exclusively modern development; medieval and Renaissance doctors were devout believers in polypharmacy. But the ease of treatment provided by aspirin (as well as its analgesic successors) represents a sea change in humans’ control over our own bodies and sensations. Physical pain—“the greatest evil,” as Saint Augustine once described it—can today be overpowered by a little white pill.

LASIK

In his original 2003 Superman series, David Plotz wrote about laser-perfected vision, which was intended to restore patients’ vision to 20/20, the naturally perfect state of the eye. The procedure, then entering its second decade of widespread practice, uses laser beams to slice out corneal cells. These lasers then reshape the cornea to make the focal point of the eye focus perfectly on the retina. In a nearsighted eye, the cornea is overly curved, and the laser flattens it; in a farsighted eye, the cornea is too flat, and the operation makes it rounder.

The primary purpose of LASIK is to correct vision. But in recent years, doctors have discovered that it can do much more than that. As part of the procedure, surgeons create a corneal flap, which is folded back to allow access to the cornea. In LASIK’s early days, the flap was created with a microkeratome, a small metal blade that slices directly into the eye. As the technology developed, however, doctors increasingly relied upon an IntraLase laser, which is safer and easier to maneuver. Several years after the introduction of IntraLase, doctors began to notice an interesting trend: Their patients were reporting not just ordinary vision, but extraordinary vision. Their eyesight had been boosted past 20/20—in some cases, all the way to 20/12.5. That means that LASIK patients can see at 20 feet what a normal person can see at 12.5 feet—a massive improvement.

A newer treatment based on this discovery, called Wavefront-guided LASIK, uses an optical analysis program developed by astronomers to further increase patients’ chance of success. Roger Steinert of the University of California at Irvine estimates that about one-third of patients have the capacity to achieve greater than 20/20 vision through these new methods. Unsurprisingly, the procedure is already being marketed as a path to superhuman vision. That, it seems, is the cycle of technology: Inventions designed to restore lives to normalcy are quickly harnessed to enhance lives beyond our ancestors’ loftiest aspirations. What starts as live-saving inevitably becomes life-improving—if you’ve got the cash, of course. Millennia of evolution gave us to the intelligence to fix our own bodies with medicine and technology. Now, in just a century, we’ve begun to beat evolution at its own game.

Read more from Slate’s Superman series.