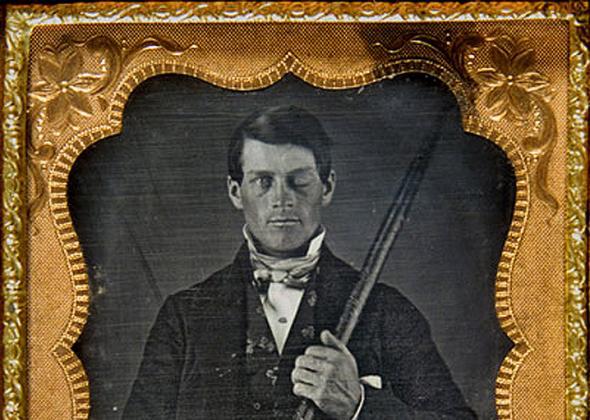

On Wednesday, Sam Kean published one of Slate’s most popular stories of 2014, “Phineas Gage, Neuroscience’s Most Famous Patient.” The piece extends from Sam’s work on his latest book, The Tale of the Dueling Neurosurgeons: The History of the Human Brain as Revealed by True Stories of Trauma, Madness, and Recovery. I asked Sam about the reaction to his piece and how he became interested in Phineas Gage.

This conversation has been edited.

Jeff Friedrich: The Phineas Gage case that people continue to learn in textbooks—why do we continue to teach it? What’s the supposed lesson?

Sam Kean: The traditional lesson is that if you get hurt in your frontal lobe, then your personality is going to drastically change. A long iron rod rocketed straight through the very forefront of Phineas Gage’s brain. It’s kind of an unusual part of the brain; you can suffer pretty severe injuries to it and often walk away from the injury. It’s not a part of the brain that’s necessarily vital for your biological self. But it is very important for personality. The supposed lesson about the Gage story was that if you get injured in this part of your brain, your personality is going to change drastically and you might even lose something essentially human.

How did you arrive at your interest in this story?

S.K.: Well, I was writing a book about some of the most dramatic and fascinating injuries in neuroscience history. It’s one of the stories that everyone knows. Whenever I mentioned the book, people said: “Oh, like Phineas Gage!”

You know, in the beginning, I thought, maybe I’ll just skip the Phineas Gage story. I wasn’t sure I could add anything. But I felt like I had to at least mention him.

And then when I started to look into it, this whole world opened up to me. I thought, wow, this is not only a different story than what many people hear. It also has some big lessons about the brain’s resiliency, about how scientific myths get made. I realized that the story many of us hear just isn’t true, and that in many ways, the real story is more interesting and more fascinating.

Why didn’t we retell the hopeful parts of his story? Why does it seem like we were culturally predisposed to make Phineas, in the phrasing of your piece, “break bad?”

S.K.: I think it was a simpler lesson to learn. And at the time, when people were resistant to the idea of the brain playing a role in personality, it might have been easier for people to accept an exaggerated story. The other reason, I think, is that while there are some records from the doctors who examined him, they’re sort of vague and it’s easy to read them in a lot of different ways. I think it’s a natural human tendency, when you read something, you tend to read a lot of your prejudices into it. And neuroscience is like a lot of disciplines – it has fashions, things change. With Phineas, people would read his story in different ways in different eras.

In The New York Times, you wrote:

For whatever reason, past neuroscientists twisted the facts about Gage to their own ends, unwilling or unable to see the real man beneath.

I am guilty of promoting these distorted views as much as anyone, and in reflecting recently on why, I realized that I’d stumbled into a sort of “uncanny valley” of neuroscience.

For example?

S.K.: Before I wrote this book, when I recounted the famous brain injury cases, like Phineas or H.M. or others, I would emphasize the change that had taken place, their deficits, the way that their lives were suddenly different.

And the reason I did that was because that’s how neuroscientists learned about the brain for centuries. They would look at changes after some event. But the more I read about these people, the more I realized that you could lose sight of the person underneath. Their brains still largely worked like ours do. They might lose their memory for certain things, but they could still walk and talk. They could still emote, feel passions, and suffer. There’s a lot more than just the deficit. The deficit is what makes these people important and unique to neuroscience, but if you really want to understand how the brain works, you need to look at the deficit in the context of all the other things that the brain can still do.

I noticed that Rebecca Skloot tweeted about your article.

Rebecca wrote The Immortal Life Of Henrietta Lacks, a book that explores the life of Henrietta Lacks, whose cancerous cells were cultured in a lab and continue to be used in important medical research today. It strikes me that Phineas and some of the brain injury patients you’re profiling share a somewhat similar history: they’ve left an important legacy to science but didn’t necessarily consent to participate in the research that surrounds them.

S.K.: It is a little uncomfortable sometimes. These are just normal people who became very important to science because of this one thing that happened to them. Nowadays, the scientists would usually leave them anonymous, which would give them some protection. But they didn’t have those protections back in Phineas Gage’s day.

Even now, it’s a little uncomfortable. You do feel like you’re peeking at these people’s lives, that it would be different if we were exploring something interesting about their liver or their kidneys. I mean, this is their brain. It’s their personality, their psychology, how they interact with their family, loved ones. So again, one thing to keep in mind when you look at these people, is that they are, for the most part, full individual people. They suffered these injuries through no fault of their own. We really should be grateful to the people who participate in research and allow certain details to be published about themselves. Because if they didn’t, we wouldn’t have nearly the understanding of the brain that we do.