Read the rest of Laura Helmuth’s series on longevity.

At the beginning of this series of stories about why lifespan has doubled in the past 150 years, we asked you to tell us why you’re not dead yet. We got hundreds of responses through email and Twitter (using the hashtag #NotDeadYet), and even more on Facebook and the comments sections of the story.

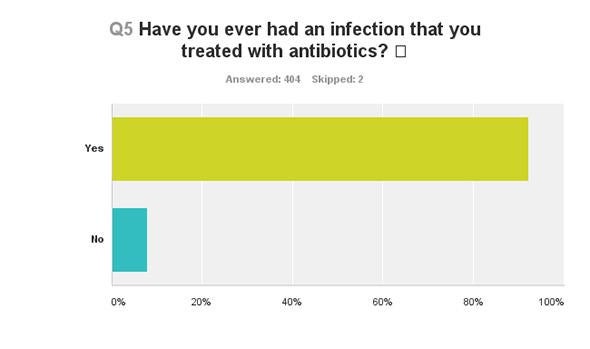

The responses were fascinating. The most commonly cited lifesavers were antibiotics and medical interventions during childbirth. Lots of people are alive thanks to emergency appendectomies. Others have ongoing life support from pacemakers, asthma inhalers, or insulin pumps. Some were treated with antivenins for snakebite. Many people had horrible accidents in childhood (one poor guy inhaled a sewing needle) and are lucky they ever made it to adulthood. Congratulations on being alive!

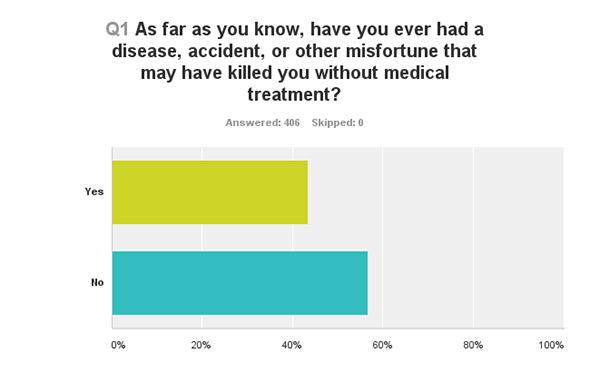

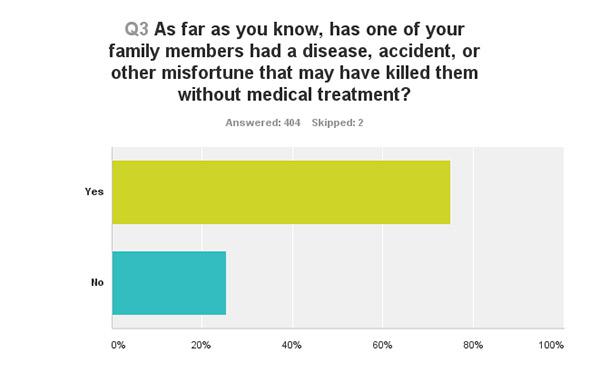

We also ran a survey with our partners at SurveyMonkey, who collected responses from 400 people using the SurveyMonkey Audience. Almost half of the respondents said they would have died without medical care, and three-fourths of them would have lost a family member. The results are below, along with a word cloud of the disasters people reported having been spared from.

Courtesy of SurveyMonkey

Courtesy of SurveyMonkey

Courtesy of SurveyMonkey

Courtesy of SurveyMonkey

Thanks very much to everyone who emailed or tweeted their stories. Here are 50 chilling, surprising, or heartwarming ones that will make you glad to be alive.

Roy: Almost every day I get out of bed with the thought that I am in life’s bonus round. Diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes at 14, here I am 47 years later. Born just 30 or so years earlier, I would’ve been dead before I hit 15. Even with the good luck to be born in 1952, I am way past my predicted expiration date. I was told my lifespan would be shortened by 15 to 20 percent. Doing the math, I figured 50 would be the outside limit of my lifespan.

Rachel: When I was 7, I thought the best thing about being in the hospital was that they’d bring you ice cream whenever you asked for it. I’d had a ruptured appendix and didn’t realize at the time how lucky I was to be living at a point in history where emergency surgery wasn’t a death sentence.

Chris: When I was 8, I contracted a disease called Reye’s syndrome. We know now it’s caused by giving aspirin to a child with chicken pox. We didn’t know that then, in the 1970s. Dr. Peter Huttenlocher helped everyone figure it out, and he saved countless children in doing so. I slipped into a coma for three days. Mom says she remembers the look on Dr. Huttenlocher’s face when I woke up from the coma, like he was a proud papa.

Scott: I had a blockage of the bundle branch in my heart, the nerves that deliver the electric shock to my heart to make it beat. Our family doctor said that he was not sure what was wrong but that there was a new thing recently invented called a pacemaker and he felt that I would need that. In March of 1975 I had a General Electric Pulse Generator implanted in my chest. It weighed 8 ounces, which is pretty hefty for something in your chest. I have had a pacemaker now for 38 years. Without a pacemaker I would have wasted away and eventually died. I went on to college, law school, and have had a successful career as a lawyer, but I owe it all to the pacemaker.

Heather: My mom was born in 1938 with spina bifida (spine improperly formed, open hole in spine). There were no treatments at the time, so the doctors told her mother she would die. When she didn’t die after three days, her mother took her home, and they put a pie plate over the hole in her spine. Her mom dragged her around to multiple doctors, finally ending up at Johns Hopkins, where she was operated on by pioneers in orthopedic surgery. She had 20-plus surgeries before she graduated high school. They said she’d never have children, but she had two.

Heather: It’s not that dramatic, but I’ve had asthma all my life, so I’m sure one of those attacks would’ve killed me in my childhood. The Albuterol inhaler gets my vote for the greatest invention ever—unless you have asthma, you can’t imagine how frightening it is to feel your lungs tightening, the oxygen decreasing … and then the immediate, incredible relief of breathing normally again.

Anonymous: I would have bled out from a postpartum hemorrhage as a result of the manual removal of a placenta that had become too tightly attached to the uterine wall. Because it was so routine, it never felt like a near-death experience, and because of modern medicine, it really wasn’t.

Gardiner: I’m 56, the youngest of six children, all still very much alive. Without modern medicine, five of us would be dead. My two older sisters are both 10-year cancer survivors: malignant melanoma and lung cancer both cured with aggressive surgery. One brother was one of the first civilians treated with sulfa drugs in infancy. Another ran himself over with a tractor, collapsed a lung, and was saved at the ER. When I hear people denigrating modern medicine, or pining for the good old days when people took care of their medical issues themselves, it makes me sick.

Rob: I have a severe allergy to horses. That wouldn’t have gone over well in the pre-horseless carriage age. I would have been dead by 6 months, if not 6 weeks or days.

Jacob: I was born with the umbilical cord wrapped around my neck and I had aspirated fluids into my lungs. I spent the first two weeks of my life in the intensive care unit. I’m alive today because my parents chose to take advantage of modern medicine and a competent obstetrician. If I had been born 150 years ago, I would not have survived birth.

Richard: It is interesting to reflect on the number of sublethal health threats that we all endure and survive easily because of modern medicine. Aside from severe things like cholera, think of simple bacterial food poisoning, which I have suffered maybe 10 times in my life (largely from traveling to places where sanitation was poor). Before modern water purification, refrigeration and such, those episodes must have been pretty common in ordinary life, even of the wealthy.

Anonymous: I’m alive because of psychological therapy, a treatment that wasn’t routinely employed until the 1950s. If not for a gifted and extraordinarily helpful therapist, I’m almost positive I would have killed myself around age 17. I wonder how many people committed suicide in prior generations who could not be helped by some talk therapy or even by a simple prescription for Zoloft.

Amanda: 361 days ago I was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes. If this date had been prior to 1920, I would likely have been six feet under by now. At diagnosis I realized fully the miracle of modern medicine and experienced a level of elation previously never experienced. That elation was indescribable, and to this day I feel bursts of it at unplanned and unpredictable moments.

Sara: I am a survivor of the rarest form of a rare disease, saved by a science that was only imagined by the likes of Mary Shelley long ago and not yet reliable 20 years ago. I was diagnosed with veno-occlusive disease, a rare form of primary pulmonary hypertension. My lifesaving double lung transplant was 9½ years ago.

Nicholas Duchesne provided reporting for this story.

Read the rest of Laura Helmuth’s series on longevity.