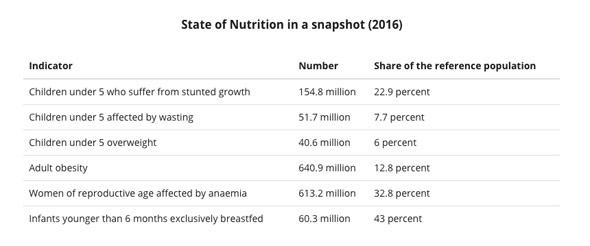

The takeaway from this year’s United Nations report on food security around the globe is bleak—after a decade of declining, hunger is up, with almost 40 million more people estimated to be going hungry in 2016 than in 2015. Throughout the report, the stats on hunger are paired with equally jarring stats about the worldwide rise in obesity, which also continues to skyrocket.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

While the increase in hunger is making headlines, the numbers in the report make it obvious that the world is facing food problems on multiple fronts. An estimated 815 million people are going hungry at the same time that more than 700 million people, including more than 100 million children, are obese. While hunger’s ability to kill makes it vivid in our minds, obesity, which has doubled since 1980, is tied to a host of health issues, too, including diabetes, high blood pressure, and an increased likelihood of stroke.

It’s easy to see hunger and obesity as two infuriating but separate issues—a baffling manifestation of a split world, of the haves and the have-nots. But in reality, the numbers are actually two sides of the same coin: A startling portion of the world does not have access to reliable, nutrient-rich food. The undernourished obviously suffer this problem, but in many cases, those who end up obese suffer from a lack of access to nutritious food, too.

A recent piece from the New York Times helps to explain how “solving” malnutrition can actually swing the pendulum to the other side, toward obesity, and underscores the value of a more nuanced understanding of global nutrition. The story documents Nestlé’s efforts to expand its business in South America—and the resulting sugar-fueled public health crisis. It describes how companies that make processed food have successfully sold their products to the poor, yielding an entire class of people who aren’t exactly going hungry but aren’t necessarily eating well, either:

A New York Times examination of corporate records, epidemiological studies and government reports—as well as interviews with scores of nutritionists and health experts around the world—reveals a sea change in the way food is produced, distributed and advertised across much of the globe. The shift, many public health experts say, is contributing to a new epidemic of diabetes and heart disease, chronic illnesses that are fed by soaring rates of obesity in places that struggled with hunger and malnutrition just a generation ago.

The new reality is captured by a single, stark fact: Across the world, more people are now obese than underweight. At the same time, scientists say, the growing availability of high-calorie, nutrient-poor foods is generating a new type of malnutrition, one in which a growing number of people are both overweight and undernourished.

In many places, obesity and hunger are not tragic antagonists but troubling twins. Yet the U.N. is still focused primarily on hunger, defined by the agency as chronic undernourishment, or being regularly unable to acquire a suitable daily caloric intake. This focus on lack of calories, as opposed to lack of nutrients, is clearest in the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals. On the list of 17 world-changing metrics to meet by 2030, the second goal is “zero hunger,” which focuses almost exclusively on problems of low caloric intake. The third goal, a seemingly all-encompassing effort to achieve “good health and well-being” for all, doesn’t mention obesity, either. (The U.N. isn’t oblivious to the other public health crisis. In a Q&A accompanying the report, the U.N. acknowledges that in many nations, and indeed in some households, obesity and food insecurity coexist, as some poor people turn to cheap, low-nutrient foods.)

But if we’re going to solve these coexisting problems, we need more nuanced data that could help us better understand the two problems, says international development expert Christopher Barrett. Despite being chided for taking a simplistic approach to defining “hunger” in years prior, the U.N. still relies primarily on calories to measure it, largely ignoring nutrient density and access to essential minerals like iron and vitamin A. “It’s very important to understand how narrow that measure is,” says Barrett, a professor at Cornell University. Obesity, meanwhile, is determined on a wholly different metric, BMI, which is not tied to calorie intake or food quality but simply to a person’s size (and has its own problems).

As situations like what’s happening in South America demonstrate, calorie counts say nothing about food quality. We don’t just need to hit a certain number of calories to be healthy—it’s nutrients that are essential to good health, the key to preventing devastating side effects of both malnourishment and obesity. As long as the U.N. and other agencies are unable to collect and share robust data on these smaller but ultimately more important dietary details, the value of its food security reports remains limited.