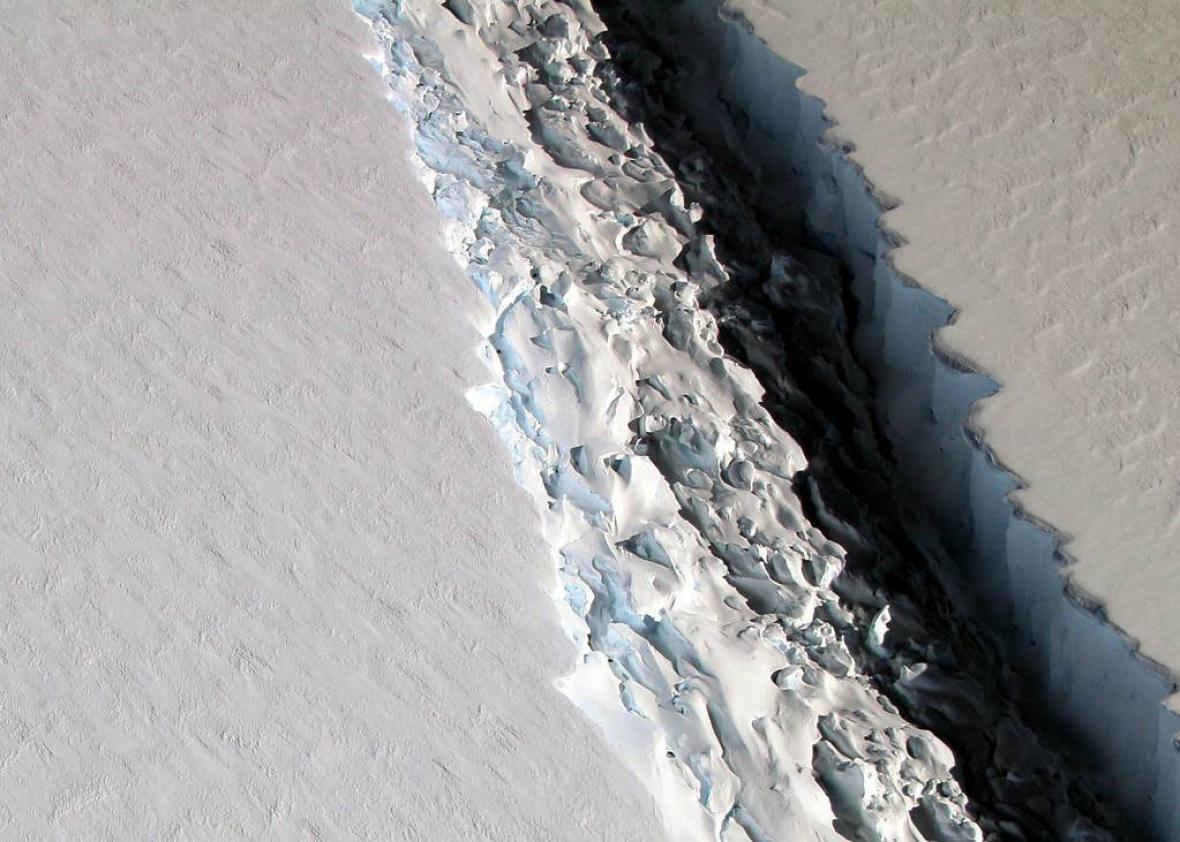

On July 12, when one of the largest icebergs ever recorded broke away from Antarctica’s Larsen C ice shelf and into the Weddell Sea, no one was around to hear it. But over the next two weeks in Chicago, tens of thousands of people will get to listen to what the calving might have sounded like, thanks to a public art installation that uses scientific data to reimagine the massive event. And it was massive. The iceberg, known technically as A68 and colloquially as the “White Wanderer,” is the size of Delaware––and the culmination of a 120-mile crack that had grown over several years.

Chicago-based artists Petra Bachmaier and Sean Gallero (aka Luftwerk) created a seven-minute audio track that simulates the sound of the Antarctic break. Their work makes use of data gathered by University of Chicago glaciologist Douglas MacAyeal, who has studied Antarctic ice for 40 years. MacAyeal records seismographic data of glaciers to understand the way the ice flows and responds to climate change—to do this, he places seismometers, machines that look sort of like halved watermelons, on selected areas of Antarctic ice, leaves the instruments for a year, and then returns in the next research season to collect his equipment, which contain a year’s worth of seismic data for him to analyze.

One of MacAyeal’s seismic recordings is of B15, an iceberg he had been monitoring for years, which broke off from Antarctica in 2000. MacAyeal calls B15 the “body double” of A68; the processes by which these two icebergs calved are remarkably similar. Luftwerk, whose work was supported by the Natural Resources Defense Council, sped up and reinterpreted these seismic signals to make them audible to the human ear and then condensed the data into a seven-minute track that loops throughout the day.

Four waterproof speakers at 2 North Riverside Plaza in downtown Chicago amplify the sounds through a plaza that 30,000 people, many of them commuters, pass through each day. At the risk of sounding obvious, sounds echo in an urban landscape, which heightens the intensity of this sound installation. The volume also oscillates—some parts are loud, others whir and buzz at levels that are almost inaudible, then it becomes tinkly and jolting before cycling back to inaudible.

At its loudest and highest pitch, more people glance up. In the quieter moments, people move about their business as usual. Some passersby think they’re hearing penguins, or a malfunctioning audio system, or miscellaneous rumbles from the city’s soundscape. Some people wander right on past without looking up from their smartphones. Those wearing headphones don’t hear anything out of the normal. Others glance up but still hurry to their next destination. But a small handful stop and pause to listen deeply or approach the signs that explain the basics of the composition.

The premise of “White Wanderer” is to transform a public place that people walk through every day, to create new possibilities for conversations on climate change in an otherwise normal city plaza. Starting a conversation about climate change can be awkward––trust me, I know. For the past three years, I’ve been wearing a cardboard sign around my neck as I travel through 16 countries on a mission to record 1,001 conversations on water and climate change. On one side, the sign says, “Tell me a story about water” and on the other, “Tell me a story about climate change.” I like to joke that the water side is my “social side”—everyone has a story about water, but unless I’m at a climate change conference or rally, stories about climate change are harder for people to think of on the spot.

“White Wanderer” creates a story about climate change that people will want to tell. The experience of listening to Antarctic ice is both extremely visceral and totally new––the longer you spend with the piece, the more you feel drawn to it. It’s the kind of art that seeps slowly into your consciousness over time.

It’s also harder to ignore a problem when you’ve heard the voice of someone who is impacted. And that’s exactly what Luftwerk, NRDC, and Doug MacAyeal have done with this exhibit—they have given a voice to ice and translated that voice to make it audible to human ears. It’s a reminder that art can start a conversation. It invites people in. “White Wanderer” is also highly portable and easy to replicate in other urban spaces—it’s an exhibit that I want to see in Houston and Roanoke, Virginia, and Montgomery, Alabama, and Jefferson City, Missouri.

In an urban landscape, it’s so easy to fall into routine. Our lives in a city are filled with the vibrations of machines: an airplane passing overhead, buses bumping over bridges, regular train schedules, and ambulance sirens. “White Wanderer” puts those urban sounds in dialogue with the calving Antarctic ice and brings something real and jarring out of obscurity and into our daily lives. It asks us to wake up from our routine. I hope it is loud enough to be heard.