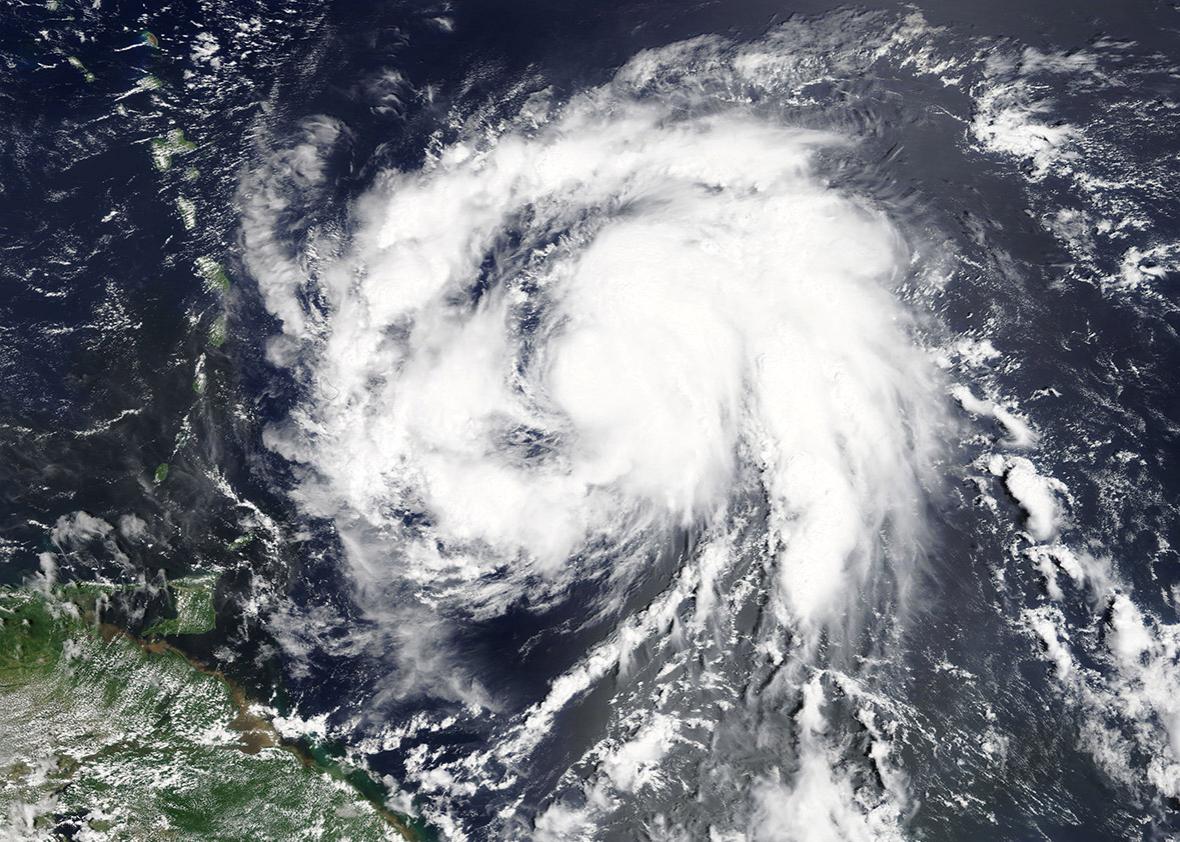

When Hurricane Harvey churned into Texas last month, it made landfall as a Category 4 storm, meaning its sustained wind speed was between 130 and 156 miles per hour. The categorization is determined via the well-known Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, developed in 1971. Category 4 implies “catastrophic damage will occur” as winds severely damage houses, power poles snap, and trees uproot.

The storm did cause catastrophic damage, but it wasn’t thanks to its winds. Harvey rapidly weakened on the coast and was quickly downgraded to a tropical storm, booting it down and off the hurricane scale. Its malice came from spinning in place while it dumped several feet of rain. It devastated Houston by water instead of speed. Damages are estimated to be up to $180 billion, rivaling 2005’s Hurricane Katrina for the costliest natural disaster in U.S. history.

In this instance, the Saffir-Simpson category ranking did not accurately capture the storm’s potential for destruction. Neither did it work for Hurricane Sandy in 2012, which only ever reached a Category 2 rating, and in fact was unranked when it made landfall in the Northeastern U.S. One of the reason’s Harvey was so destructive is because it lingered for so long—but the potential durability of a storm doesn’t factor into the Saffir-Simpson metric. Yet duration is one of the main cost drivers of hurricane devastation—especially for lower category storms like 1 or 2, or, in Harvey’s case, storms not on the scale at all. Which is why we need a better way of measuring hurricanes.

“I’m not alone among meteorologists who think the time has come to replace [the Saffir-Simpson scale],” wrote Dan Satterfield, chief meteorologist for WBOC-TV in Salisbury, Maryland, and a blogger for the American Geophysical Union. While their numbers don’t yet make the Weather Channel—which admittedly has provided ever more information to viewers about wind speeds, storm surges, and potential for inland flooding—scientists and meteorologists are actively looking for replacements for our category ranking system: some kind of number that will more reliably indicate the damage a storm is expected to bring.

One storm metric meteorologists have used for decades is “Accumulated Cyclone Energy,” or ACE. It’s proportional to the square of the wind speed, measured and summed every six hours. (The square is used, because, like the kinetic energy of a car or cat, energy of motion increases as the second power of velocity.) It’s tabulated religiously every day in hurricane season, for each storm, then totaled for the year. But one immediate problem with ACE is that, despite its name, it can’t convey the energy of a storm, because it doesn’t take note of a storm’s size.

For hurricanes, size is of paramount importance. Hurricane Katrina surprised inhabitants of the Gulf Coast with its storm surge and destruction in 2005 in part because it made landfall in Mississippi as only a Category 3, with 125 mph sustained winds. Many in its way expected it to be nothing like the monstrous Hurricane Camille of 1969, still the second most intense hurricane to ever strike the U.S., which came ashore as a Category 5 with breathtaking winds of 190 mph.

But Katrina’s maximum winds went out to a radius of 30 miles, double that of Camille’s, so the volume of water it put into motion was four times larger. As a result, Katrina’s storm surge was higher than Camille’s all across the coast, and economic losses 14 times greater.

Sandy, busting Asbury Park’s Madame Marie and a great deal else, was the physically largest storm to ever hit the U.S., with a wind field 1,100 miles across. It caused about $79 billion in damages.

There are metrics that include storm size to better estimate a storm’s total energy, like IKE (integrated kinetic energy), developed in 2007. Another is the Hurricane Severity Index, developed by the private company ImpactWeather (since acquired by StormGeo) in 2006.*

But the best metric to replace our current category system would be one that can measure what we most need to know about an impending hurricane—how damaging it will be. And that’s what the Cyclone Damage Potential measures—the capacity to cause damage. It includes wind speeds and storm size, but also storm duration and how the storm’s wind field will move. James Done of the National Center for Atmospheric Research and colleagues at NCAR and in the reinsurance industry developed it. CDP predicted that Harvey would be bad, much worse than did Saffir-Simpson. It ranks storms on a scale from 0 to 10—Harvey was a 5.2 at landfall, Irma a 5.9 when it made landfall in the Florida Keys, and Maria a 4.2 upon landfall in Puerto Rico. Katrina was a 4.9, Sandy a 3.0, and Hurricane Andrew of 1992 came in at 2.9.

One of the more pressing reasons behind our need for a better metric is the worry that climate change will increase the frequency and intensity of hurricanes in the future. Done’s CDP work is funded by a global reinsurance broker, Willis Towers Watson—a company he says is specifically interested in climate change because “they understand it will impact their bottom line.” (This is a reassuring converse to Upton Sinclair’s pithy line that “It’s hard to get a man to believe something when his salary depends on his not believing it.”)

It’s hard to know how much a more accurate prediction could have helped Houston prepare for the damage heading its way last month. Transitioning from the simple and widely known 1–5 scale to a subtler index built on more information might be tricky for the people who have lived in hurricane zones for years and have their own internal barometers of how to respond. But as we brace for an uncertain future, better metrics can only help.

*Correction, Sept. 25, 2017: This sentence has been clarified to include that StormGeo acquired ImpactWeather in 2012. (Return.)