Plant-based food company Hampton Creek recently announced its plans to bring lab-grown meat into stores within the next year. It’s an ambitious plan, and there are good reasons to be skeptical of its claim—the plant-based mayonnaise company’s business practices have been persistent targets for critics, drawing accusations of bad science, mislabeling, and even instructing employees to buy its mayonnaise off the shelves to drive up sales numbers. Hampton Creek is also hoping to beat its competitors to market by about two years, despite its late entry into “cultured meat”—a bold target that has others in the industry skeptical of the company’s claims.

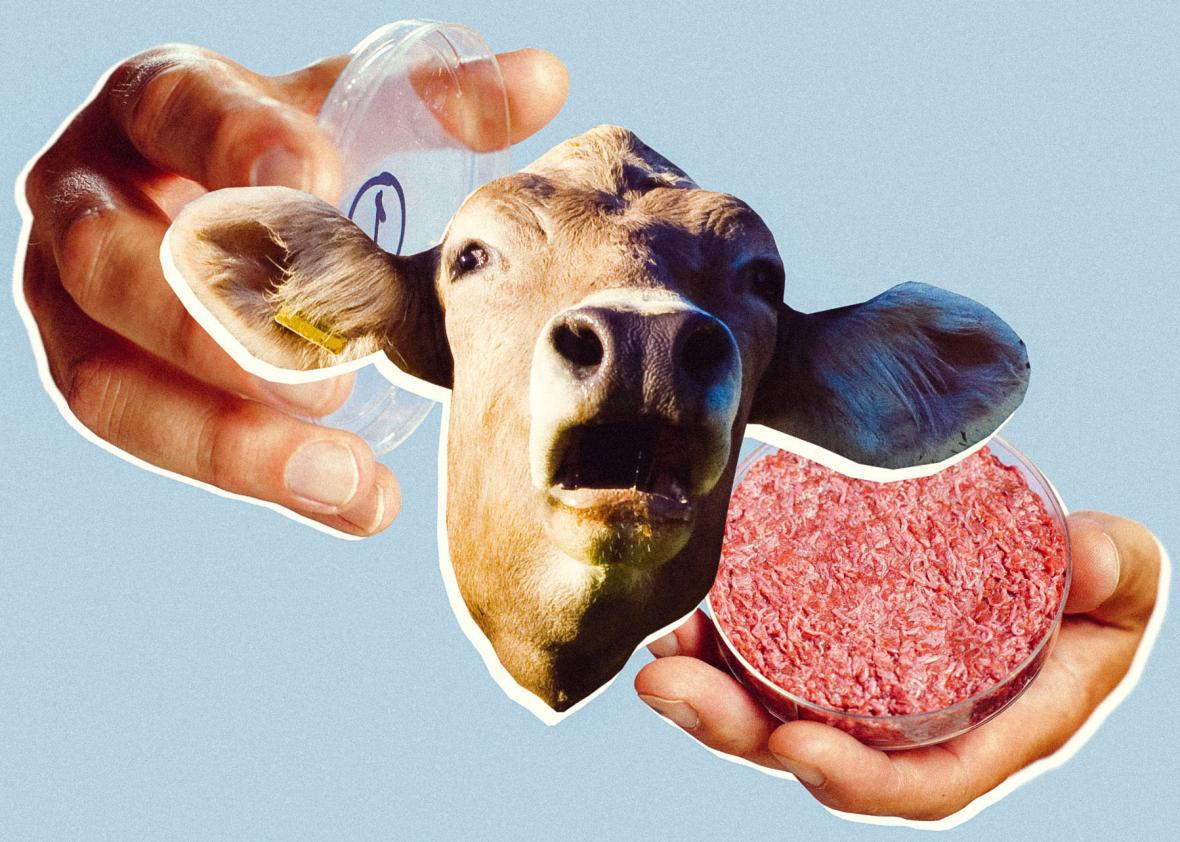

The whole point of lab-grown meat is to create a more sustainable product that doesn’t require the hassle and waste of cattle production—it’s meat grown in a lab rather than on a set of bones. If Hampton Creek wins (and thus far it’s come out on top in the majority of its controversies), it could be the first to create “meat” grown using plant nutrients only.*

Hear this article on Slate Voice! slate.com/voice

Yes, all lab-grown meat so far requires a product called fetal bovine serum. What is fetal bovine serum? Why does it exist? Where does it come from? What else is it used for? It turns out that FBS is a somewhat common product, and one that we have to thank for many a medical innovation. Let’s explore.

FBS, as the name implies, is a byproduct made from the blood of cow fetuses. If a cow coming for slaughter happens to be pregnant, the cow is slaughtered and bled, and then the fetus is removed from its mother and brought into a blood collection room. The fetus, which remains alive during the following process to ensure blood quality, has a needle inserted into its heart. Its blood is then drained until the fetus dies, a death that usually takes about five minutes. This blood is then refined, and the resulting extract is FBS.

Millions of fetuses are slaughtered this way. Although cows and bulls are kept separate to preclude the possibility of horseplay, most dairy cows, which are kept pregnant to ensure milk production, are eventually slaughtered too. Estimates put the percentage of slaughtered dairy cows found to be pregnant between 17 and 31 percent.

Why is fetal cow blood used to make fake meat in the first place? Let’s back up: Cultured meat grown in a lab is made from bovine cells that grow in a petri dish to ultimately produce a substance that is meatlike enough to market as a burger—because it’s made of the exact same cells. And cells, the basis of this substance, are notoriously suicidal. Usually, this is a good thing: In order for distinct body parts to develop and for those body parts to keep working, cells must be able to kill themselves if they realize they’re in the wrong place. That’s great in a body, but it means that when you put cells in a plastic dish (like a lab technician would do when growing fake meat), the cells are going to do their best to die. FBS stops their deaths because it contains growth factors, substances that can lie to cells and convince them they’re right where they should be.

FBS isn’t the only serum that can be used to culture meat cells, but it is the most widely used, even among other cow-blood products. Jan van der Valk, a scientist in the department of animals in science and society at Utrecht University, explained that cow fetuses are “organisms in development.” That means their blood contains more growth factors than older cows’ blood, making it better for cell culture and growing cultured meat.

FBS is also special because it is a universal growth medium. You can take almost any cell type, toss it into a petri dish with FBS, and the cells will grow. Other sera don’t have that universality. Instead, they’re cell-specific, so if you want to grow muscle tissue, you use muscle tissue serum, and if you want to grow brain tissue, you use brain tissue serum. So, while FBS could one day be used to make everything on a charcuterie board, other non-FBS alternatives would require multiple sera to make the pâté, liver, and sausage.

But, even though FBS is currently convenient, using it defeats the purpose of cultured meat in an extremely obvious way: You’re still slaughtering cows. Why not just eat the meat from the cow instead of going through a laborious process that turns cow cells into other cow cells? As it stands, cultured meat isn’t vegetarian, which means it can’t be marketed to vegetarians or vegans, many of whom oppose meat because of the cruelty of the meat industry or the environmental intensiveness of the meat industry. Cultured meat grown by way of FBS doesn’t, at all, address that problem—in fact, when it comes to the moral argument, slaughtering and extracting fetal blood from an unborn cow is possibly a more disturbing way to get meat.

But it’s not like FBS is only used in cultured meat. The use of the serum is extensive, with FBS being cited in more than 10,000 research papers, far more than other cow blood products. These papers cover a lot of research topics. FBS has been used in the development of vaccines for many types of cancer, influenza, HIV, and hepatitis, as well as to help understand the development of brain and muscle tissues. Still, there is a movement to reduce its role in vaccine development, partly for ethical reasons, but also because it’s a public health concern. Vaccines created with FBS can transmit mad cow disease, and although transmission is extremely unlikely, your chances being about 1 in 40 billion, the Food and Drug Administration has strongly discouraged its use for the past 25 years. Van der Valk sees this risk as being especially bad in cultured meat. “If you grow meat using a serum that is infected with disease, you can transmit it to people,” he told me.

Despite the FDA’s recommendations, however, FBS is still widely used because it’s the most convenient. There are alternatives—People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals has a list of 74 potential cell culture alternatives, but almost all are cell-type specific. Of the alternatives that can be used as universal growth media, platelet lysates are most used, but they come with their own issues—at least when it comes to making cultured meat.

Platelet lysates are made from the platelets that can be extracted from human blood samples. Because of the incredibly strict requirements on the blood used in human blood transfusions, the FDA expires blood five days after it is donated. Oftentimes, when it expires, rather than throwing it out and wasting a perfectly good sack of blood, a lab will turn it into platelet lysates and sell it as a serum for cell culture. That makes platelet lysates a great alternative for human research. But it can’t be used for cultured meat because, as van der Valk pointed out in wonderfully understated fashion, people may be hesitant to consume meat that was created from human blood. He does, however, “see [platelet lysates] as an in-between step” in going from using animal products to using completely animal-free sera. And, according to Bruce Friedrich, director of the Good Food Institute, all companies working on cultured meat will have to find alternatives to FBS, because it will no longer practical to use the serum once the product scales.*

Hampton Creek will attempt to create a cultured meat that relies on plant products instead of animal-based products like FBS or human-based products like platelet lysates. Will customers eat it? Four years ago, Daniel Engber argued in Slate that cultured meat just didn’t taste right and that people wouldn’t eat it because of that. Another major hurdle is human psychology—Engber made the prescient point that people think stuff grown in labs is weird, asking, “Why wouldn’t lab-grown meat be attacked with the same degree of holy venom?” Still, the fact that it won’t make use of extracted fetal cow blood could certainly be a selling point.

Correction, July 13, 2017: This story originally misstated that Hampton Creek is the only company attempting to make meat without fetal bovine serum. Other companies are also attempting this. It also has been updated to note that companies may soon have to find alternatives to FBS. (Return.)