This story is being co-published with the Genetic Literacy Project.

On Thursday, Science published a large-scale study on the relationship between bees and a pesticide, neonicotinoids. It got quite a bit of pickup in the press—Nature touted that the “Largest-Ever Study of Controversial Pesticides Finds Harm to Bees,” while the BBC explained that a “Large-Scale Study ‘Shows Neonic Pesticides Harm Bees.’ ” The Scientist said the same, with “Field Studies Confirm Neonicotinoids’ Harm to Bees,” and PBS followed suit with “Neonicotinoid Pesticides Are Slowly Killing Bees.”

These headlines seem to reflect a line included in the abstract of the study itself: “These findings point to neonicotinoids causing a reduced capacity of bee species to establish new populations in the year following exposure.”

Sure sounds like a bummer for the bees. One problem: The data in the paper (and hundreds of pages of supporting data not included but available in background form to reporters) do not support that bold conclusion. No, there is no consensus evidence that neonics are “slowly killing bees.” No, this study did not add to the evidence that neonics are driving bee health problems.

Unfortunately, and predictably, the overheated mainstream news headlines also generated a slew of even more exaggerated stories on activist and quack websites where undermining agricultural chemicals is a top priority (e.g., Greenpeace, End Times Headlines, and Friends of the Earth). The takeaway: The “beepocalypse” is accelerating. A few news outlets, such as Reuters (“Field Studies Fuel Dispute Over Whether Banned Pesticides Harm Bees”) and the Washington Post (“Controversial Pesticides May Threaten Queen Bees. Alternatives Could Be Worse.”), got the contradictory findings of the study and the headline right.

But based on the study’s data, the headline could just as easily have read: “Landmark Study Shows Neonic Pesticides Improve Bee Health”—and it would have been equally correct. So how did so many people get this so wrong?

This much-anticipated two year, $3.6 million study is particularly interesting because it was primarily funded by two major producers of neonicotinoids, Bayer Crop Science and Syngenta. They had no involvement with the analysis of the data. The three-country study was led by the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, or CEH, in the U.K.—a group known for its skepticism of pesticides in general and neonics in particular.

The raw data—more than 1,000 pages of it (only a tiny fraction is reproduced in the study)—are solid. It’s a reservoir of important information for entomologists and ecologists trying to figure out the challenges facing bees. It’s particularly important because to date, the problem with much of the research on neonicotinoids has been the wide gulf between the findings from laboratory-based studies and field studies.

Some, but not all, results from lab research have claimed neonics cause health problems in honeybees and wild bees, endangering the world food supply. This has been widely and often breathlessly echoed in the popular media—remember the execrably reported Time cover story on “A World Without Bees.” But the doses and time of exposure have varied dramatically from lab study to lab study, so many entomologists remain skeptical of these sweeping conclusions. Field studies have consistently shown a different result—in the field, neonics seem to pose little or no harm. The overwhelming threat to bee health, entomologists now agree, is a combination of factors led by the deadly Varroa destructor mite, the miticides used to control them, and bee practices. Relative to these factors, neonics are seen as relatively inconsequential.

I’ve addressed this disparity between field and lab research in a series of articles at the Genetic Literacy Project, and specifically summarized two dozen key field studies, many of which were independently funded and executed. This study was designed in part to bridge that gulf. And the devil is in the interpretation.

According to the lead researcher Richard Pywell of the CEH:

We’ve shown for the first time negative effects of neonicotinoid-coated seed dressings on honeybees and we’ve also shown similar negative effects on wild bees. … Our findings are a cause for serious concern.

I agree that there might be cause for serious concern if the studies had shown convincing evidence of negative effects. But a review of the data—by the GLP and independent scientists—concludes differently. The European study focused on three types of bees placed in fields across three countries—Germany, Hungary, and the U.K. As Jenna Gallegos noted in her particularly nuanced analysis in the Washington Post:

[T]he results were not as clear-cut as experts had hoped. … The differences between bees in treated or untreated fields were largely insignificant, and many of the bees in both groups died before they could be counted.

Overall, the data collected from 33 different fields covered 42 analyses and 258 endpoints—a staggering number. The paper only presented a sliver of that data—a selective glimpse of what the research, in its entirety showed.

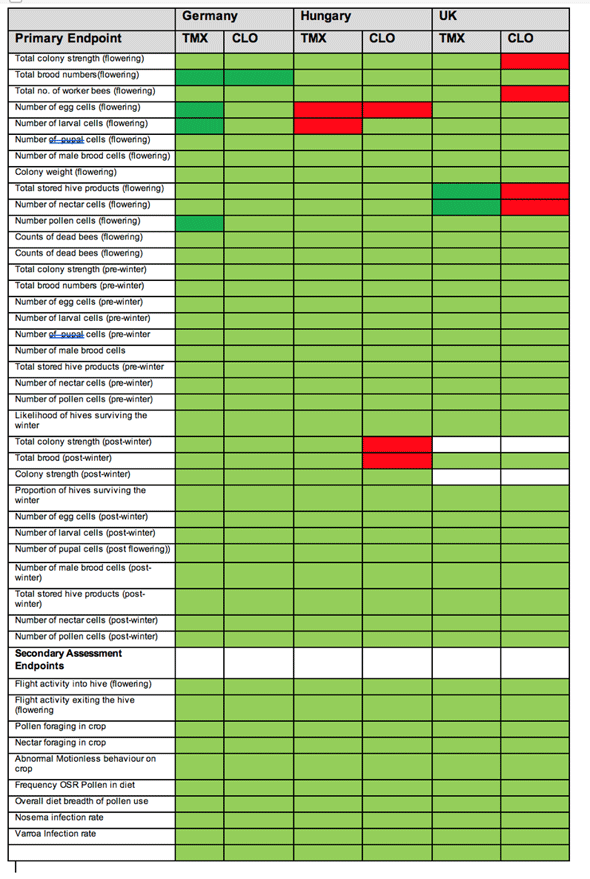

What patterns emerged when examining the entire data set? Here is a chart assembled from data supplied to the research funders by the CEH (but not released in the published study) with the findings summarized (light green indicates “no impact,” red points to “negative impact,” and dark green suggests neonics had a positive impact).

Dr. Peter Campbell Sr., environmental specialist and head of product safety research collaboration, Syngenta

In sum, of 258 endpoints, 238—92 percent—showed no effects. (Four endpoints didn’t yield data.) Only 16 showed effects. Negative effects showed up 9 times—3.5 percent of all outcomes; 7 showed a benefit from using neonics—2.7 percent.

As one scientist pointed out, in statistics there is a widely accepted standard that random results are generated about 5 percent of the time—which means by chance alone we would expect 13 results meaninglessly showing up positive or negative.

Norman Carreck, science director of the International Bee Research Association, who was not part of either study, noted, the small number of significant effects “makes it difficult to draw any reliable conclusions.”

When pressed, even Pywell acknowledged the conflicting data.

The data were rife with other contradictions. Worker bees and drones in Britain struggled to survive the winter, but the same variety of wild bees increased in Germany. Egg production also increased in Germany but fell in Hungary.

The health problems seemed to have little to do with pesticides. A fungal infection ran roughshod over Hungary’s bees. In Britain, they were decimated by the deadly and unrelenting Varroa destructor mite—even the controls suffered losses 400 percent greater than the national average. These catastrophic loss numbers suggest the field experiments may have been poorly constructed—raising doubts about the standard of research for the entire research project.

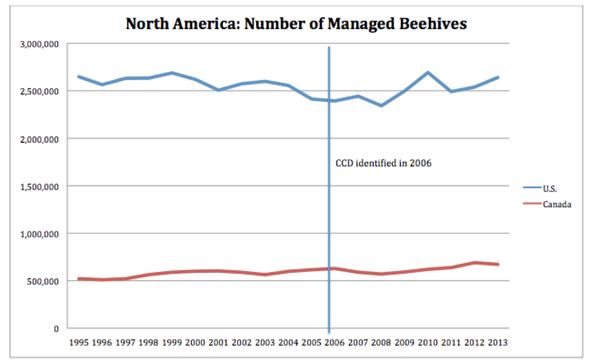

The broader context of the bee health controversy is also important to understand; bees are not in sharp decline—not in North America nor in Europe, where neonics are under a temporary ban that shows signs of becoming permanent, nor worldwide. Earlier this week, Canada reported that its honeybee colonies grew 10 percent year over year and now stand at about 800,000. That’s a new record, and the growth tracks the increased use of neonics, which are critical to canola crops in Western Canada, where 80 percent of the nation’s honey originates.

Managed beehives in the U.S. had been in steady decline since the 1940s, as farm land disappeared to urbanization, but began stabilizing in the mid-1990s, coinciding with the introduction of neonicotinoids. They hit a 22-year high in the last count.

Genetic Literacy Project

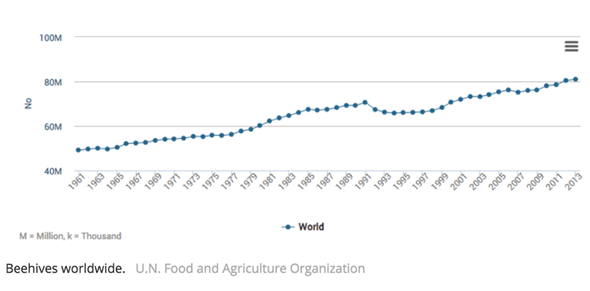

Global hive numbers have steadily increased since the 1960s except for two brief periods—the emergence of the Varroa mite in the late 1980s and the brief outbreak of colony collapse disorder, mostly in the U.S., in the mid-2000s.

U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization

So the bees, contrary to widespread popular belief, are actually doing all right in terms of numbers, although the Varroa mite remains a dangerous challenge. But still, a cadre of scientists well known for their vocal opposition to and lobbying against neonics have already begun trying to leverage the misinterpretation of the data. “In the light of this new study, continuing to claim that use of neonicotinoids in farming does not harm bees is no longer a tenable position,” David Goulson, a University of Sussex bee biologist, known in anti-neonic circles as a scientist-for-hire, told the U.K.’s Science Media Centre.

But other, less ideologically invested scientists were far more circumspect. “We learn again: It’s complicated,” said biologist Tjeerd Blacquière of Wageningen University in the Netherlands. The mixed findings are likely to intensify ongoing debates about restricting or banning the compounds, with both sides claiming vindication.

The study, while problematic and contradictory in its results, is not without value. It has underscored that it’s possible or even likely that exposure to miticides or insecticides—including neonics, which like all insecticides are designed to target insects—increases the vulnerability of bees to disease and other threats. But that could be said about any chemical, including organic treatments. In Europe, where neonics have been banned since 2013 (based almost entirely on disputed lab studies), farmers have turned to alternatives that are far more toxic to both bees and humans, such as Lorsban and pyrethrins. Canola production is down, and bee health has shown no appreciable change. Farmers are in open revolt, and bees are arguably the worse for it.

Within hours of the release of the study, advocacy groups opposed to intensive agricultural techniques had already begun weaponizing the misreported headlines.

“It shows that industry claims that neonicotinoids do not harm bees at field-relevant concentrations are baseless,” said a Greenpeace senior scientist, a marine biologist with no background in entomology.

“Pressure mounts for a complete ban on neonicotinoid pesticides as landmark study confirms these chemicals are harming bees,” wrote Friends of the Earth.

But viewing the date from the European study in context makes it even more obvious that sweeping statements about the continuing beepocalypse and the deadly dangers to bees from pesticides, and neonicotinoids in particular, are irresponsible. That’s on both the scientists, and the media.