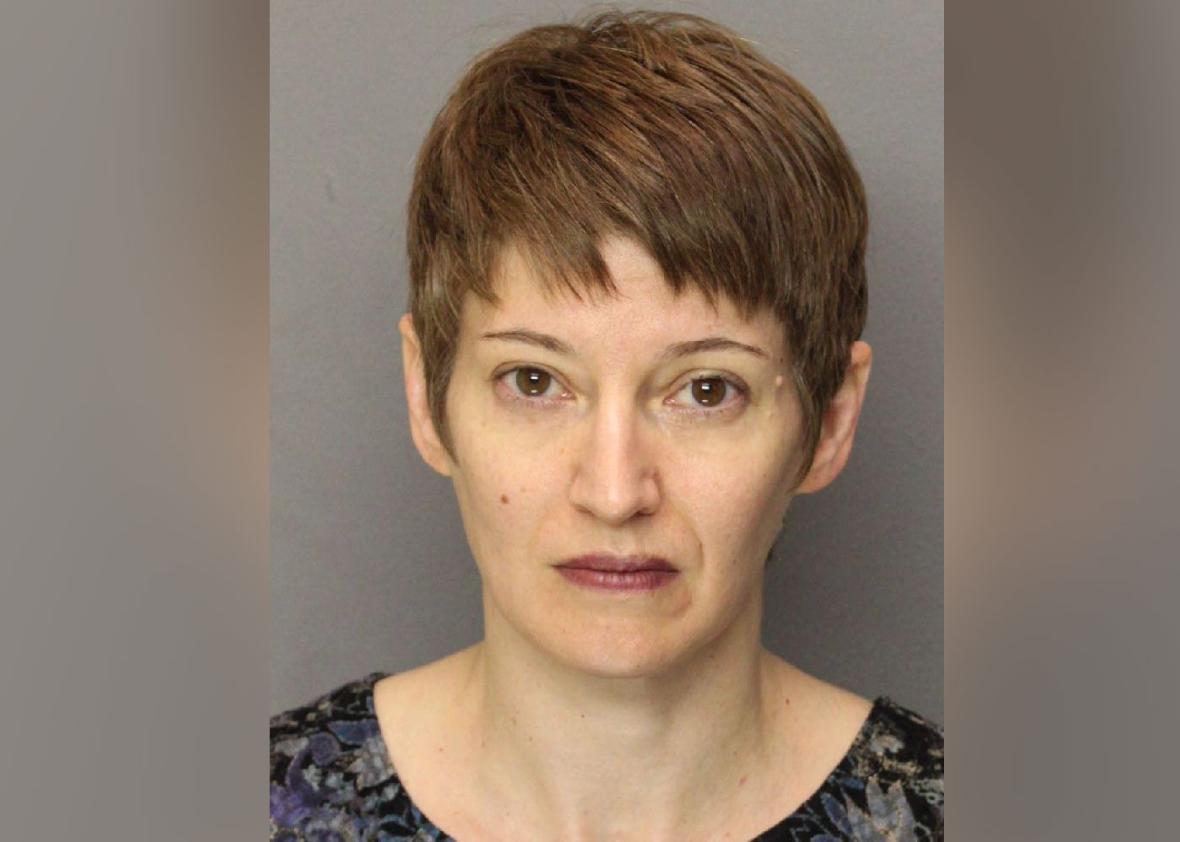

In 2015, former Rutgers philosophy professor Anna Stubblefield was found guilty of raping a mute young man with cerebral palsy. Last week, a three-judge panel overturned that conviction, ruling that the judge in Stubblefield’s original trial unfairly excluded evidence related to the man’s capacity to give consent. Now the Supreme Court of New Jersey will have a chance to weigh in. Unless it overrules the appellate court’s unanimous decision—in a process that could take months—the 47-year-old Stubblefield, who has been serving a 12-year sentence at the Edna Mahan Correctional Facility for Women, will qualify for a second trial.

While the appellate court was definitive in its determination that Stubblefield did not get a fair shake, it did not do much to resolve the tricky scientific issue at the center of her case. Stubblefield says that “D.J.” (as the victim is known in court documents) had consented to their sexual relationship by means of “facilitated communication,” a practice meant to help nonverbal people with disabilities express themselves by typing. (An FC practitioner typically steadies her client’s shoulder, arm, or hand as he reaches out to punch letters on a keyboard.) In the lead-up to the trial, the presiding judge, Siobhan Teare, decided to exclude any evidence related to FC or stemming from its use, on the grounds that it isn’t based on well-accepted science. The appeals court now says that her blanket ban was too severe and that it prevented Stubblefield from mounting a full and vigorous defense.

If Stubblefield does end up getting a second trial, several important but excluded lines of evidence would be allowed in court. But the appellate court’s critique of Judge Teare’s approach fails to give a satisfying answer to the overarching question of how FC should be handled in the courtroom. In that sense, it has only made things more confusing.

The decision starts with an outline of the facts of the case: For two years, Stubblefield used FC to help D.J. type out messages. The text they produced together proved D.J. had been misdiagnosed for many years, she said: While he may have been unable to speak or hold a pencil, he had no cognitive impairments. (Several expert assessments in the preceding years had come to the opposite conclusion.) With the help of Stubblefield and a portable keyboard, D.J. managed to audit a class at Rutgers, publish an academic paper (now retracted), and present his work at conferences. Eventually, she says, he spelled out his love for her—and his consent to having sex.

At trial, the prosecution argued that FC is a lie—a sham technique that has been debunked many times before. Whether Stubblefield realized it or not, prosecutors claimed, she was herself the author of the typed-out messages; she’d been guiding D.J.’s finger to certain letters on the keyboard and spelling out the words she guessed or hoped that he would say. (“Porn exploits women and you’re more beautiful than any porn star,” she said he typed at one point during their romance. “I’d rather just be thinking about you when we make love.”) That is to say, her relationship with D.J. was, if not a predatory con, then a Ouija-board fantasy. (For more details on this complicated case, see my feature for the New York Times from October 2015.)

As I explained in Slate in April, Judge Teare ruled in advance of Stubblefield’s trial that facilitated communication would be considered junk science. According to New Jersey law, any scientific test results—i.e., those related to “a subject matter that is beyond the ken of the average juror”—can be admitted only if the tests in question are “generally accepted, within the relevant scientific community, to be reliable.” Even Stubblefield’s lawyers acknowledge that FC is not “generally accepted” by any broad community of experts. Heavy scrutiny of the method in the early 1990s, when FC was at the peak of its popularity, showed that practitioners’ typed-out messages were sometimes inauthentic. Since then the method has been widely disavowed.

In practice, this meant Stubblefield’s lawyers couldn’t show the jury any messages D.J. was said to have spelled into his keyboard, nor could they ask any witness other than Stubblefield herself to testify about that typing or what it said. As a result, the jury heard a fractured narrative. When she told her story of the relationship with D.J. from the stand—an intense, two-year bond, carried out through long and thoughtful, typed-out conversations—it seemed unmoored from any real-world facts. She sounded like someone ticking through the plot points of a dream she’d jotted in her journal.

The defense attorneys also were not allowed to have FC’s inventor, Rosemary Crossley, testify about the method. Nor could they present Crossley’s own videotaped assessment of D.J., conducted after Stubblefield was taken into custody, which purports to show that D.J. can indeed communicate without assistance.

The appellate judges took issue with almost all of these exclusions, but their ruling starts with the banning of the Crossley tape. In the course of testing D.J., Crossley had, at times, used facilitated communication: She’d held his shoulder, his arm, and his hand, and helped him point to targets on a board, with those targets representing answers to a set of questions. But Crossley says there were other times during the assessment when D.J. reached out to the targets without assistance. In 12 hours of testing, D.J. is said to have answered 45 such questions on his own and gotten 43 of them correct. That’s convincing proof, according to Stubblefield’s lawyers, that he’s intelligent and capable of providing sexual consent.

Before the trial, the prosecution had countered that even in these snippets of the testing, Crossley influenced D.J.’s answers. When she wasn’t holding his arm, she was holding the targets—and that meant she could have moved or tilted the board of multiple-choice answers in subtle ways. If she’d been giving her covert (and perhaps unconscious) assistance, then even random movements from D.J. might have led him to the correct targets. (Crossley has been accused of doing exactly this—moving a target so as to elicit a correct response—years ago in another case.)

“I was very careful to hold the devices steady,” Crossley told the court at a pretrial hearing in January 2015. But Judge Teare disagreed: Based on her own appraisal of the videos, along with a skeptical report from a prosecution expert, she decided that Crossley hadn’t been careful enough. The judge said that while she couldn’t tell if Crossley had been influencing the answers, the data and methods on display in the video “were similar to facilitated communication rendering her analysis invalid.” In other words, even if the technique that Crossley used to elicit those 45 answers did not meet a strict, formal definition of FC (since she wasn’t touching D.J.’s arm), it was close enough to make it unreliable. The video would fall under Teare’s umbrella exclusion of FC as junk science.

In Friday’s ruling, the appellate judges called this decision a mistake. Teare had privileged her own impressions of the videotape over those of the jury, they said. Why should her opinion as to whether Crossley moved the targets be any more valid or important than the jurors’ views? By “erroneously [using her] own assessment of the videotaped interaction between Dr. Crossley and D.J.,” she’d deprived Stubblefield’s lawyers of the chance to argue that the assessment was, in fact, “accurate and not based on FC.”

That’s janky reasoning. It would be one thing if the judges found that Crossley’s methods in the video were substantively different from FC, as formally defined, and that Judge Teare was therefore wrong to keep them out of court. But the appellate ruling makes a different point. It suggests that Teare was playing fair when she barred FC ahead of trial but that she’d somehow overstepped her role in deciding for the jury that Crossley—the inventor of FC and its leading global advocate—had been using that technique in the video. The judge should never have taken it on herself to say whether Crossley’s methods were “accurate and not based on FC,” the judges ruled. This was the jury’s job: “The court’s observations of Dr. Crossley’s videotaped evaluation were no better than the jury’s observations would have been.”

This distinction is an awkward one. New Jersey’s rules on scientific evidence are meant to safeguard jurors from deciding technical questions—anything that might be “beyond their ken.” But if the validity of FC itself is beyond a juror’s ken, then how could it be within her ken to figure out whether Crossley’s methods amounted to a version of FC?

Imagine if the Stubblefield case hinged on a different sort of scientific evidence or method—not facilitated communication, but, say, an experimental lab technique for testing degraded DNA. Would we ask a jury to examine a video of scientists at work, spinning out nucleic acids in a centrifuge, and then make them figure out exactly which technique it shows, and whether that technique is “accurate”?

The appellate judges seem to think that methods of helping people to communicate represent a special, simpler sort of science—one that can be eyeballed and appraised by your average jury. The facts don’t support this understanding, though. In cases where FC has been shown to be inauthentic—and the client’s typing turned out to be controlled by the facilitator—the illusion wasn’t something you could “see” by looking hard enough. It took rigorous, scientific testing to reveal the error.

While the appellate court’s views on facilitated communication are extremely muddled, it’s not as if Judge Teare’s reasoning was a model of clarity. At a pretrial hearing in April 2014, she announced that she’d been mystified by the contradictory expert reports on Crossley’s videotaped assessment: How could “two people looking at the exact same thing” have opposite views on whether D.J. was answering the questions on his own? “At that point I realized I need to see the thing myself and make my own conclusion,” she said. The judge thought that she could “see” the truth herself.

Teare then launched into a strange soliloquy about how D.J.’s ability to communicate was, in fact, irrelevant to the charged crime. The back-and-forth over the videotape “has been a very interesting exercise,” she told the lawyers at that hearing, “but at some point in reading this … I was like, you know what, I’m too involved in the forest, I need to deal with the tree.” The “tree” was the fact that D.J. had already been declared legally “incompetent” by the state, which made him unable to consent no matter what he did or said. It wouldn’t make a difference if he could reach out to targets on his own, or even if he could speak without a problem. “D.J. may have an ability to communicate, I don’t know. But that’s not ultimately the question here,” Teare said. Stubblefield’s crime was akin to a statutory rape: Underage girls “can verbalize, they can talk,” said Teare. “But the reality is if someone that’s four years older than them has sex with them, it’s a crime. And there’s nothing anyone can do about it.”

Then, after some further discussion with the lawyers, she abruptly changed her mind: “I don’t believe [D.J.] really can communicate, I’m sorry,” she told them. “It’s unfortunate. But I think that’s a reality.”

Given that Stubblefield’s trial seemed to hinge on this very question, that exchange was rather alarming. So was Teare’s statement during sentencing, cited by the appellate court, that Stubblefield’s actions had been “the perfect example of a predator preying on their prey.” In the three years I’ve spent reporting on this story, this may have been the most absurd quote I ever scribbled in my notebook. Stubblefield could have been wrong about D.J.; she may have been delusional in her love for him and criminally reckless in her desire to have sex; she may have been arrogant, self-righteous, unconsciously racist, and even predatory in her behavior. But to read the facts of her convoluted and troubling case and conclude that she’s a “perfect example of a predator” is to say that down is up and black is white.

The appellate court ruled on Friday that, in light of that predator comment and “in an excess of caution,” Teare should be removed from the case. If there is a second trial, a different judge will be in charge. That’s a good thing.

In addition to the Crossley tape, a retrial would include more crucial pieces of evidence that Teare excluded in the original trial. First, the jury would be allowed to hear from a witness named Sheronda Jones. Stubblefield had trained the former Rutgers student to use FC with D.J. and to help him type out essays for his class on black American literature. At one point in 2011, Jones told investigators that D.J.’s homework assignments—on works by Zora Neale Hurston, Frederick Douglass, and Frances Harper, among others—included information about the books that she didn’t know herself. At the original trial she was not allowed to talk about the content of those essays or any other words that showed up on the screen of D.J.’s keyboard. This deprived Stubblefield of the chance to show that she was not the only one who thought that D.J. could communicate.

When Stubblefield was arrested, the police took possession of D.J.’s keyboard and downloaded all its data. Some of the keyboard text appears to have been typed with Jones’ help or under her control. (Once again, the authorship of these messages has been disputed.) Sheronda, it says, you are very pleasant to work with. The same exchange includes some words on Stubblefield, too: I believe in God. Anna doesn’t. I hoping she doesn’t go to hell.

Then there are the typed-out messages from Stubblefield’s final visit to D.J.’s home. At that point she’d already told D.J.’s family that she was having sex with him, and they’d implored her to stay away. Nevertheless, Stubblefield came back to continue the discussion. During that visit, D.J.’s brother asked a pair of questions about one of their relatives, whom Stubblefield didn’t know.

The first question, “Who is Georgia?” referred to D.J.’s aunt’s sister, who used to care for him sometimes. Georgia in high school worked for mom, D.J.—or Stubblefield—typed, according to a download of the keyboard’s text.

Then D.J.’s brother asked another question, using Georgia’s nickname: “Who is Sally?” If it were really D.J. typing, he’d know that Sally and Georgia were the same person. If Stubblefield were the author, she’d be stumped.

You said one question, D.J. or Stubblefield typed. I’m very under pressure, because you are making me pass tests to keep any chance of having anna in my life.

The next few lines of the keyboard log read like someone stalling, or bristling:

I answered the first time.

Enough.

It’s the principle.

How many times will you break your word?

Finally, D.J. or Stubblefield typed out half an answer to the question: Georgia in our family circle is mom’s little nephew’s ki …

When D.J.’s brother shook his head, D.J. or Stubblefield typed out in desperation, how am i supposed to know who you mean? i know you think i should know, but i just don’t. but that doesn’t prove i’m not typing my own words.

For D.J.’s family, it proved exactly that. The test had been definitive: Stubblefield was the author of D.J’s words, which meant her relationship with D.J. had been a lie. He never gave consent to her advances, and that simple fact made her a rapist.

Stubblefield’s lawyers would like to tell a jury this shows that D.J. passed his brother’s test. Who is Georgia? As D.J.’s aunt’s sister, she was, in fact, his “mom’s little nephew’s kin.” This must have been what D.J. tried to type, the defense argued on appeal—in which case it would have been “a completely accurate and sophisticated answer” to the question and “highly probative of the conclusion that it was D.J. who was communicating.”

If the jury had been given the chance to see all this evidence—from the videotaped assessment, from Sheronda Jones, from the Georgia-Sally test—would it have arrived at the same guilty verdict? “The factual setting here was extraordinary,” the appellate judges wrote on Friday, “and it called for a liberal admission of evidence … to allow [the defendant] the opportunity to convince the jury of the reasons for her unorthodox perception of D.J.’s capabilities.” If their ruling holds, Stubblefield will get that opportunity.