In a somber speech to its board of trustees delivered on Feb. 21, Stanford University’s ex-provost John Etchemendy warned that intolerance is the greatest threat facing American universities today. Adding his voice to a growing bipartisan chorus, Etchemendy argued that liberal academics too often assume their opponents are evil or stupid, turning institutions of higher education into unproductive echo chambers instead of arenas for open debate. “Intellectual monocultures … have taken over certain disciplines,” he observed grimly. “The university is not a megaphone to amplify this or that political view, and when it does it violates a core mission.”

On March 2, protesters at Middlebury College appeared to confirm Etchemendy’s fears. In response to a planned lecture by author and social scientist Charles Murray, students and other activists shouted Murray down, mobbed his car, and hospitalized the professor tasked with interviewing him. Condemnation was swift from the left and the right and, as Osita Nwanevu described for Slate, mixed sensible condemnation of violence with familiar critiques of campus intolerance. The New York Times editorial board worried that university lecterns are being yielded to “intolerant liberals.” Yale University law professor Stephen L. Carter criticized the ideology of “intolerant college students,” linking it to the work of the Marxist philosopher Herbert Marcuse, who famously argued that in an unjust society pure tolerance is both impossible and undesirable.

Intolerant is an effective slur, but critics who deploy it fail to recognize that intolerance is often desirable. Something did go wrong at Middlebury, but it certainly wasn’t due to students’ intolerance. Indeed, higher education couldn’t function without intolerance. When Etchemendy criticized universities’ “intellectual monocultures,” for example, it’s a safe bet he wasn’t talking about their biology departments, even though nearly half of all Americans—creationists—would likely feel unwelcome in them. And he can’t possibly think that immunology faculties would be improved by the addition of a few vaccine skeptics, even if their views are politically well-represented across the country.

Etchemendy was talking about political intolerance. But only an extreme moral relativist would claim that science has a monopoly on settled truths and that we should therefore tolerate all political arguments. The idea that civil liberties shouldn’t be doled out on the basis of race, gender, or religion is no longer controversial because the opposing view is no longer tolerated. Moreover, it’s naïve even to treat politics and science as separate categories. Opposition to universal civil rights drew on shoddy science, just as fallacious belief in creationism informs some people’s antipathy to public schooling. How can universities engage in climate science without being intolerant of politicians who refuse to believe it?

Accepting that intolerance is a force for good can be difficult. This is especially true for liberals, who now find themselves the target of a slur they were instrumental in weaponizing. Liberal rhetoric has long made it seem as if all intolerance is bad. Locke and Voltaire argued that religious zealotry’s central flaw was intolerance, and now intolerance has become an eighth sin, the perceived engine of history’s worst atrocities. As a result, social progress is inevitably framed in terms of eradicating intolerance. As the novelist and social activist John Irving wrote in a recent essay: “Tolerance of intolerance is unacceptable.”

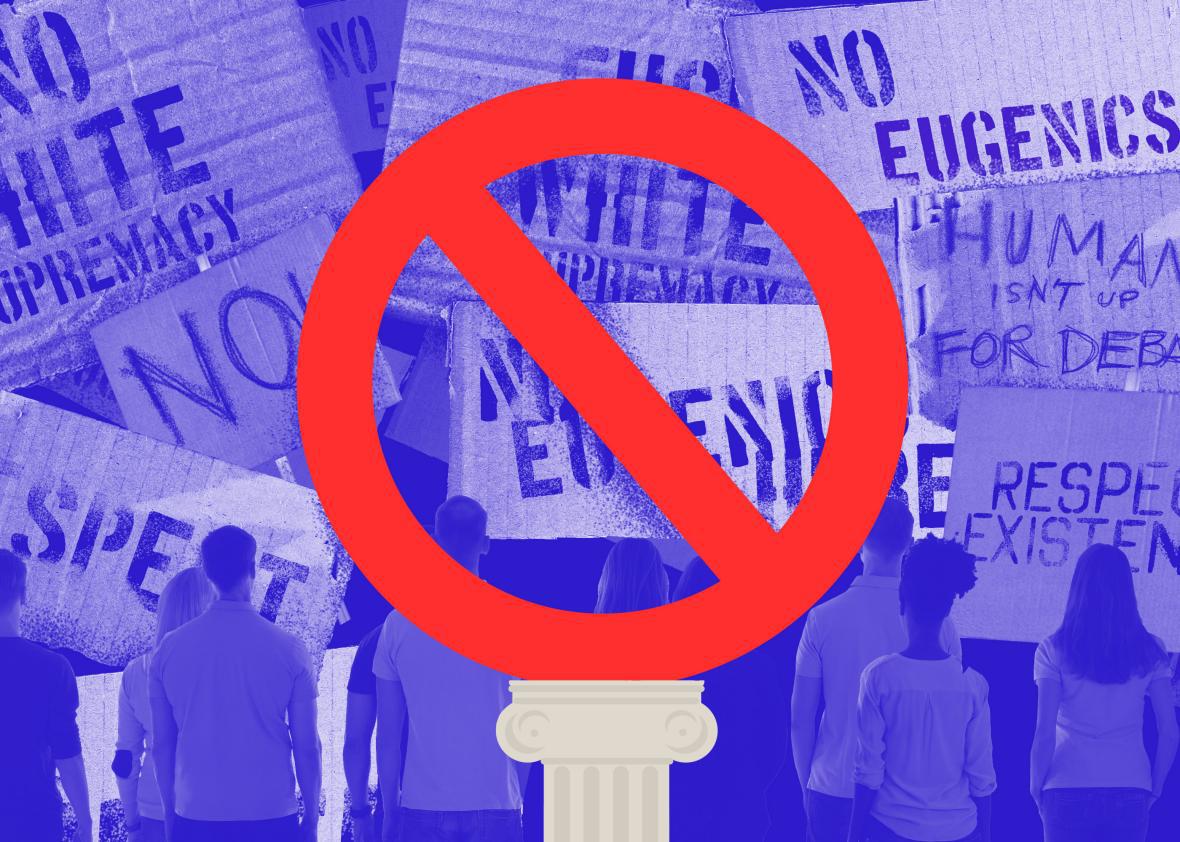

This, of course, is nonsense. Declaring anything unacceptable is itself an act of intolerance, and the resulting paradox suggests that intolerance isn’t the best target. Instead of saying that intolerance of Jews and other minorities led to the Holocaust, it’s more accurate to blame hatred, based on horrifically misinformed understandings of what constitutes humanity. Likewise, biologists reject creationism not because it is intolerant of evolution, but because it is wrong. The same is true when immunologists reject vaccine skepticism. White supremacists, creationists, and vaccine skeptics refer to their exclusion from higher education and mainstream media as a form of intolerance. And they’re right—academic institutions are intolerant of their views. Yet we can all agree that Stanford needn’t change its hiring practices. Those who strive to stamp out these dangerous views are intolerant, but justly so.

By championing tolerance instead of truth or goodness, the left has opened itself up to unavoidable accusations of hypocrisy. Take Jonathan Haidt, a prominent social psychologist whose work on the extent of liberal bias in higher education has been embraced by both the right and the self-critical left. When pressed about what exactly we should tolerate, Haidt distinguishes between what he calls “fundamentalist and non-fundamentalist religions.” On his account, “the religious right and radical Islam are fundamentalist movements, and they are incompatible with modernity, democracy, and the ineradicable diversity of all Western societies.”

Should we tolerate them? No way, says Haidt: “If I could wave a magic wand and have all fundamentalists converted into non-fundamentalists overnight, I would do so and be confident the world would become a better place.”

But wait. By saying he’d like to get rid of fundamentalists, isn’t Haidt engaging in textbook intolerance? After all, the religious right is one of the most powerful grassroots movements America has ever seen and a cornerstone of Republican political successes. It’s hard to see how wanting to magic away their beliefs is compatible with an expansive vision of tolerance that would bring ideological balance to secular universities.

This kind of inconsistency is easily avoidable once you realize that tolerance is a means to an end, not an end in itself. John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty made it clear that the marketplace of ideas, with its attendant ideals of political tolerance, civility, and free speech, was never meant to ensure the eternal coexistence of all opinions but to facilitate the elimination of falsehood and immorality without violence, bias, or coercion. You can favor ideological balance in universities—read: tolerance—not only to ensure that unpopular truths get heard, but also as an effective way of demonstrating the incompatibility of religious fundamentalism with basic principles of liberal democracy. An overlooked evil of censorship is that it denies weak arguments the opportunity to publicly humiliate themselves in a fair fight.

It’s also essential to recognize that intolerance does not require incivility. As I have written elsewhere, there is no contradiction between tolerating fellow citizens (or students) while remaining intolerant of their beliefs. Medical students at the University of Toronto, for instance, successfully lobbied through university channels to remove an undergraduate course in “alternative health” that promoted anti-vaccine views and used quantum physics to explain homeopathy. They were right to act intolerantly, just as Middlebury faculty were right to urge the college’s president not to introduce Charles Murray as a speaker, much of whose work they believed to be pseudoscience. The subsequent violent protests were wrong not because they were intolerant, but because they were an ineffective and immoral form of intolerance, especially in a civic space dedicated to reason and evidence. The best way to ensure the longevity of a bad idea is by giving it a cross to die on in the middle of a university.

Just as it is foolish to condemn all intolerance, it is also misguided to make strict rules about permissible forms of intolerance. No shouting. No breaking the law. The correct form of intolerance always depends on its object and its context. If Charles Murray were to hand out copies of The Bell Curve in a supermarket, it would be entirely acceptable to shout at him. Sometimes laws need to be broken—sometimes you need to sit at the front of the bus. And for all but the staunchest pacifists, violence can be a perfectly justifiable way to express intolerance when someone attacks you.

Earlier I claimed that it’s no longer controversial to think that civil liberties don’t depend on race, gender, or religion. Unfortunately, a clear-eyed assessment of the evidence shows that many people would likely embrace a return to the (not so) good old days. In this country, a congressman can publically express ethno-nationalism—“We can’t restore our civilization with somebody else’s babies”—and be praised by colleagues for it. The longtime best-selling book of Christian apologetics—C.S. Lewis’ Mere Christianity—calls for religious nationalism (“all economists and statesmen should be Christians”) and argues that God wants men to be the head of the household. These are popular ideals, but they are poisonous and deserve fierce resistance, not complacent tolerance.

The question, therefore, isn’t whether one should be intolerant of bad ideas, but how. It’s true that, as Haidt and Etchemendy argue, many liberals are too quick to dismiss their political opponents as evil or stupid or, well, intolerant. This is ineffective—the right response is to challenge their mistaken claims. Blaming intolerance is intellectually lazy and hands proponents of repugnant ideologies a powerful rhetorical move for advancing their agendas—demanding their views be tolerated, since intolerance has been deemed unacceptable.

Progress today depends, as it always has, on the refusal to tolerate falsehood and immorality. In certain circumstances proper intolerance will demand reasoned discourse; in others it will demand shouting and breaking the law. We may disagree about how to fight for what’s right, but that disagreement should come in the context of recognizing our proud participation in a long, necessary history of virtuous intolerance. Only then can we hope to defend truth unfettered by hypocrisy and self-contradiction.