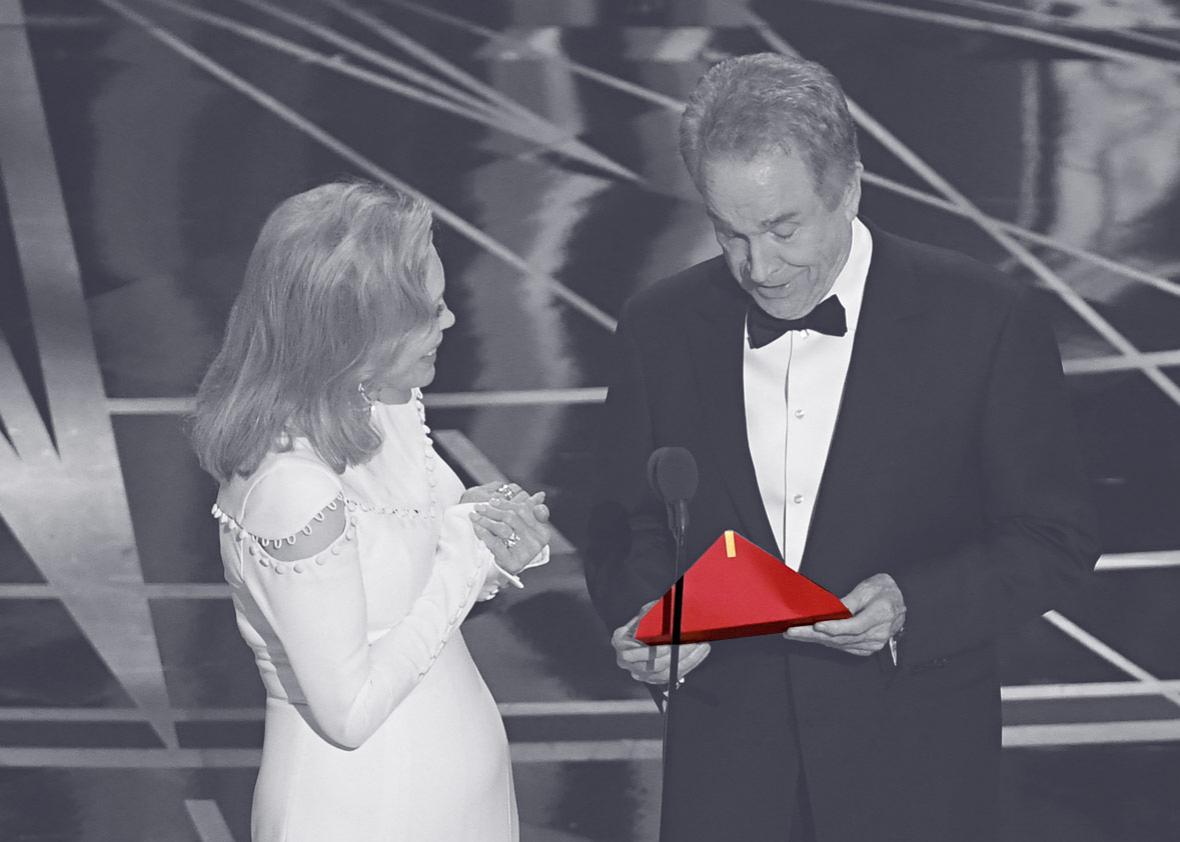

In every disaster, there’s an instant when the awful truth first presents itself to the stunned participants—a lookout spots an iceberg dead ahead, or methane gas starts jetting from the top of a drilling rig. At the 89th Academy Awards, this happened on live television, so we all got to see the precise moment Warren Beatty realized something had gone terribly wrong. His famous eyebrows arched upwards. He frowned, hesitated.

The meltdown that followed was epic. Beatty peered into the envelope again as if to see whether a second slip of paper were lurking inside. Then he handed the befuddling card to his co-presenter, Faye Dunaway, who, unaware of the disaster still, immediately announced “La La Land.” That film’s producers were more than two minutes into their speeches before the truth came out: Beatty had been handed the wrong envelope before he took the stage. Moonlight was the real winner.

This may have been an unprecedentedly public disaster, but on a historical scale this was hardly a catastrophe. No ships sank; no lives were lost. But the chain of events that led to the debacle—and the way the participants reacted to it—are familiar to anyone who has studied disasters like the sinking of the Titanic or the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Life is full of wildly unlikely outcomes—a long shot wins the presidency or a Super Bowl team overcomes a 25-point deficit. But, when disasters occur, we assume such shocking events must have appropriately massive causes. Instead, what the Oscars debacle teaches us is that the mistakes that lead to chaos are often surprisingly minor and random. Or as Charles Perrow, author of a book on accidents writes, “Accident reconstruction reveals the banality and triviality behind most catastrophes.”

Perrow, one of the pioneers in the modern science of disaster, notes that, though it would be a logical assumption, most large accidents are not the result of a single, egregious error. Rather, they are the end products of long strings of seemingly inconsequential decisions and conditions. We usually only become aware of these factors after they topple like a string of dominoes and cause chaos.

Banality and triviality certainly abound in the case of the big Academy Awards envelope switcheroo. Standing in the wings and handing envelopes to presenters as they take the stage doesn’t sound like a very complex job. But a number of factors, some stretching back for decades, converged in just the right way to enable the error. The first is a decision to allow PricewaterhouseCoopers, the accounting firm that has famously tallied Oscars voting for the past 83 years to singlehandedly manage the envelope process. The company takes great pride in its Academy Award role, so its partners Martha Ruiz and Brian Cullinan—rather than, say, stagehands or administrative staffers—personally hand the envelopes to the presenters. Ruiz and Cullinan clearly relish the ceremony of toting their black briefcases containing the winning envelopes down the red carpet. But having senior executives taking such a front-line role can be a recipe for trouble—they’re more likely to assume they’re going to do it right. Many accidents have been triggered by very experienced workers who grew overconfident and complacent—wilderness firefighters, for example, are most likely to be killed or injured in their 10th year on the job. “That’s just about the time they start to think they’ve seen it all,” says Karl Weick, a University of Michigan psychologist who studies disasters.

Cullinan, the accountant who handed Beatty the wrong envelope, was in his fourth year of doing Oscars duty and had worked for the company for more than 30 years. Compared with grinding through the accounts of global corporations, shuffling award envelopes probably seemed like a lark to him, a nice perk. Clearly, Cullinan felt relaxed in the role. He even found time to tweet a picture of Best Actress winner Emma Stone clutching her award backstage. Since the Best Actress award was the last one to be presented before Best Picture, that meant Cullinan was busy tweeting just seconds before handing out the final envelope. Staying focused while doing simple, repetitive tasks is a challenge for most people, but there is evidence to suggest that less senior workers are sometimes more attentive—the anxiety that comes from being somewhat new to a job appears to help keep people alert. U.S. Navy aircraft carriers, for example, routinely include well-trained but surprisingly inexperienced sailors on the crews that perform the dicey work of launching and recovering aircraft.

So Cullinan may have been at higher risk for making a mistake. Why was he there in the first place? The academy maintains extraordinary secrecy in order to keep the results from leaking. There is no master list of winners in the broadcast booth, and even Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences president Cheryl Boone Isaacs doesn’t know who won. The only people who know the winners in advance are the two PwC partners carrying the black briefcases. That system dates back to the 1940 Academy Awards ceremony when the Los Angeles Times broke an embargo and published the winners hours before the event. “Some Oscar guests picked up the paper on their way to the show,” says the Wrap’s Steve Pond, author of The Big Show: High Times and Dirty Dealings Backstage at the Academy Awards.

Restricting knowledge of the winners to the two PwC representatives has kept Oscars’ secrets from leaking ever since. But the practice also made it impossible for the show’s director or anyone else to know immediately that a mistake had been made. That’s an example of a precaution aimed to solve one problem inadvertently causing another, something that’s common in many disasters. Another safety procedure that went awry concerns how the envelopes are handed out: Ruiz and Cullinan each had a full set of envelopes in their respective briefcases. Ruiz stood in the wings at stage left; Cullinan handled stage right. Each time a presenter took the stage, either Ruiz or Cullinan would hand him or her the proper envelope. That meant that when the presenter entered from, say, stage left, Cullinan, at stage right, would be left with an unneeded, duplicate envelope. Why bother with all those duplicates? To be ready just in case a presenter unexpectedly entered from the wrong side. But it also creates more opportunities for the envelopes to get confused: When Leonardo DiCaprio took the appropriate envelope from Ruiz as he entered to present the Best Actress award, that left Cullinan with the unneeded Best Actress envelope. That was a planned precaution. But when Beatty swept by a few moments later, Cullinan somehow handed the actor that envelope—and not the one labeled Best Picture. A belt-and-suspenders approach, another precaution intended to solve one problem, ended up creating another.

Much of the Oscars mishap’s drama came from the fact that it occurred on the biggest, and final, award of the night. This isn’t surprising: an outsize share of accidents happen near the ends of projects or missions. The Deepwater Horizon explosion occurred after the drillers had completed the well and were preparing to remove their drilling equipment. In mountaineering, the majority of accidents happen on the descent. This is an understandable human tendency: After working hard to achieve a certain goal, it is only natural to relax a bit when you think you are over the hump. “It was the last envelope!” notes Anne Thompson, editor at large at IndieWire. “They thought they were done. They thought it was over.” Exactly.

Even the design of the envelope that Beatty carried to the stage played a role in the fiasco. Until recently, the award envelopes were gold, with large white labels designating the category. This year, the design was changed to a red envelope with more subtle gold lettering. The bright red might have looked stunning on television, but the tasteful gold letters on a dark background turned out to be much harder to read. Had the letters been more legible, it seems likely that Cullinan, Beatty, or even Dunaway might have caught the mistake in time.

Overtrained individuals, needless safety precautions, and the understandable tendency to let up at the end helped create the disaster condition. Why couldn’t one quick-thinking person stop it? When Beatty pulled the card from the envelope and saw the words Emma Stone, La La Land, he knew he’d been holding the wrong envelope. But he didn’t stop the show and say so.

In the aftermath of such events, we all like to assume we would have handled the situation correctly. But Beatty’s reaction was very much in keeping with human nature. All of us have strong mental models of what to expect in given situations. Disaster expert Weick calls this process “sensemaking.” Processing information that doesn’t fit our sensemaking models is surprisingly difficult, he says, even for experts. Beatty, no neophyte when it comes to award shows, expected the card to include the name of a single movie, not the name of an actress and a movie. He knew there was a problem. On the other hand, he’d taken the envelope directly from the hand of a partner in PwC, a firm renowned for its bulletproof reliability. And the movie the card did mention La La Land, the film everyone expected to win Best Picture.

“You can see the wheels turning in Warren’s head,” Thompson says of that moment. Beatty stalled for time. Then, with a look of mute supplication on his face, he showed the card to Dunaway. He seemed to be looking for a second opinion, hoping she would confirm his sense that a mistake had been made. But Dunaway, already annoyed by what she perceived as his showboating, didn’t hesitate. When she glanced at the card, her mind zeroed in on the words she expected to see, La La Land, and simply tuned out the words Emma Stone. Such selective attention is common in high-stress situations. The pilots on the doomed Air France Flight 447, for example, tuned out the loud stall warning—which indicated that their plane’s nose was too high for the wings to provide lift—and instead focused on keeping their wings level even as the craft was plunging toward the ocean.

Why didn’t the PwC accountants—the only two people who knew about the mistake—immediately rush to the microphone and announce the correct winner? According to veteran Oscars stage manager Gary Natoli, the two partners simply “froze.” Again, this is not unusual. Many disasters, including the Three Mile Island nuclear accident and the Deepwater Horizon spill, could have been prevented if the operators on the scene had reacted immediately to signs of trouble. The PwC partners were supposed to have memorized all the winners (and how could someone not remember who won Best Picture?), but neither one reacted. The La La Land producers began their thank you speeches. Meanwhile, backstage, it took more than a minute before Cullinan told a stage manager that he didn’t think they’d named the right winner. More time passed before someone asked Ruiz to open her envelope. “She was just standing there with the envelope in her hand, very low-key,” Natoli said.

Such seemingly lackadaisical reactions are surprisingly common in the midst of disasters. It took the crew of Deepwater Horizon more than a minute to sound the general alarm after explosive gas started enveloping the platform and even longer to disconnect the rig from the well. After the Costa Concordia cruise ship struck a rock off the Italian coast, crewmembers told passengers that the problem had been solved and to return to their cabins—even as the boat began to sink. Denial and disbelief are hardwired into human consciousness. When events deviate enough from our mental models, it can be almost impossible to comprehend what’s going on. And our tendency to freeze up in stressful situations may even reflect a primitive survival instinct: Animals that freeze, rather than run, might avoid being seen by predators.

Finally it was La La Land producer Jordan Horowitz—ironically someone with the strongest interest in believing that the movie actually had won—who stepped decisively to the microphone: “I’m sorry, there’s a mistake. Moonlight, you guys won best picture.” He had seen the correct card and knew the truth.

As in the case of so many catastrophes before it, the many causes of the Great Oscars Envelope Flap were invisible to all the participants beforehand but quite easy to see in retrospect. No doubt, the academy will reassess many of its procedures: the extreme secrecy, relying on accounting executives to manage backstage functions, those duplicate envelopes—even the color of the paper and the type. The academy has already announced that Ruiz and Cullinan will not be welcome at any future ceremony. Other fixes will be made. But, no matter how many changes are instituted, the potential for future mistakes will remain. Disasters teach us a humbling lesson: No matter how careful we think we are—and often in spite of the care we take—there’s always another string of unseen dominoes waiting to topple.