“The white working class is really struggling.” This statement has been assumed as a fact and used as an explanation to rationalize Donald Trump’s upset election. Is it true?

One major data point feeding into the narrative of the struggle is the purported increase in mortality rates among middle-aged white people in America. As Anne Case and Angus Deaton noticed a bit over a year ago in a paper that received much well-deserved attention, other countries and U.S. nonwhites have seen large declines in death rates, something like 20 percent. That finding was certainly true—but what received far more attention was their secondary point, that American middle-aged whites were not experiencing these same declines and, in fact, faced an increasing mortality rate.

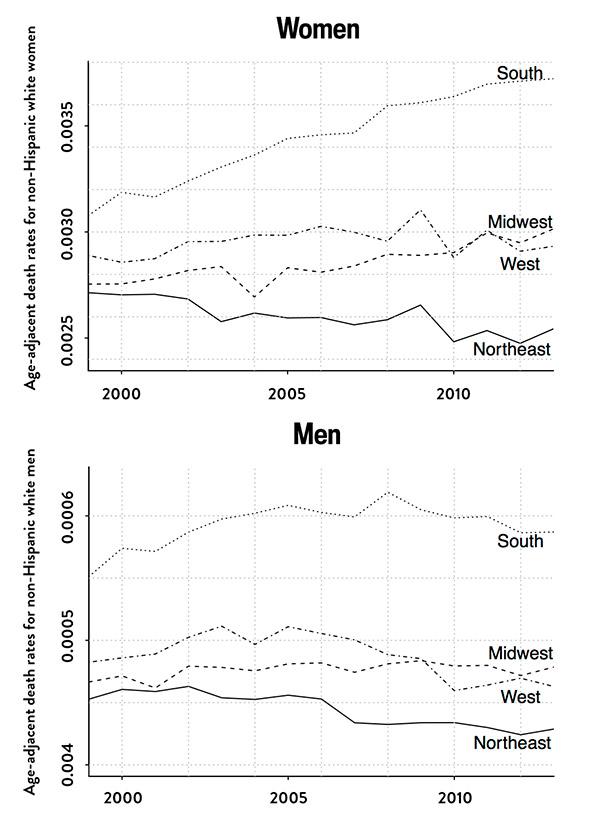

As we’ve explained before, this is not quite correct: What seems to be happening is that non-Hispanic white women, aged 45–54, are experiencing an increase in mortality, and everyone else seems to keep making gains.

Jonathan Auerbach and Andrew Gelman

And, as the graphs above show, beyond gendered differences, there are regional differences. In particular, things have been getting worse for women in the South and Midwest. But overall, there has been little change since 1999.

Now, Case and Deaton have a new paper coming out: “Mortality and morbidity in the 21st century.” (The authors note that it is the conference version of the paper, rather than the final.) In it, they report big differences in trends among whites with high and low levels of education—mortality seems to be rising for white Americans who lack a college degree and falling for those who do have a college degree. Again, it somewhat neatly ties into the dominant narrative and is certainly worth investigating.

But we’re not quite sure how to interpret Case and Deaton’s comparisons across education categories because the composition of the categories has changed during the period under study. The group of 45- to 54-year-olds in 1999 with no college degree is different from the corresponding group in 2013, so it’s not exactly clear to us what is learned by comparing these groups. We’re not saying the comparison is meaningless, just that the interpretation is not so clear.

It turns out there’s a paper from 2015 on this topic, by John Bound, Arline Geronimus, Javier Rodriguez, and Timothy Waidmann. They write:

Independent researchers have reported an alarming decline in life expectancy after 1990 among US non-Hispanic whites with less than a high school education. However, US educational attainment rose dramatically during the twentieth century; thus, focusing on changes in mortality rates of those not completing high school means looking at a different, shrinking, and increasingly vulnerable segment of the population in each year.

Bound et al. then take the next step:

We analyzed US data to examine the robustness of earlier findings categorizing education in terms of relative rank in the overall distribution of each birth cohort, instead of by credentials such as high school graduation.

That makes sense. By using relative rank, they’re making an apples-to-apples comparison. And here’s what they find:

Estimating trends in mortality for the bottom quartile, we found little evidence that survival probabilities declined dramatically.

Widely publicized estimates of worsening mortality rates among non-Hispanic whites with low socioeconomic position are highly sensitive to how educational attainment is classified. However, non-Hispanic whites with low socioeconomic position, especially women, are not sharing in improving life expectancy, and disparities between US blacks and whites are entrenched.

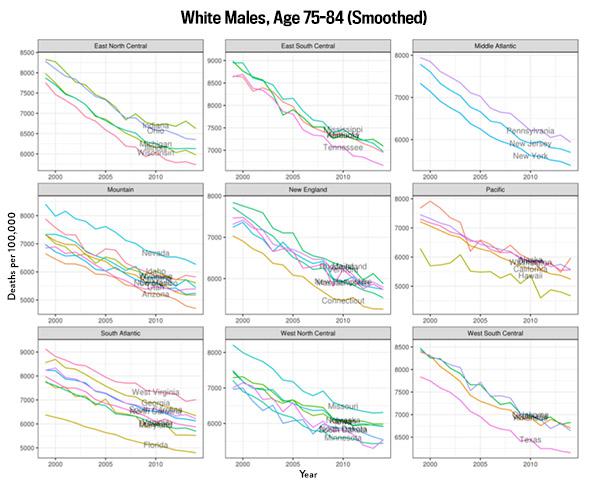

As statisticians, we’re struck by how incredibly rich the underlying data are, available free from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s website. For example, we graphed raw data and smoothed trends in mortality rate from 1999–2014 for:*

- 50 states

- men and women

- non-Hispanic whites, blacks, and Hispanics

- age categories 0–1, 1–4, 5–14, 15–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75–84

It’s amazing how much you can learn by staring at these graphs.

For example, these trends are pretty much the same in all 50 states:

Jonathan Auerbach and Andrew Gelman

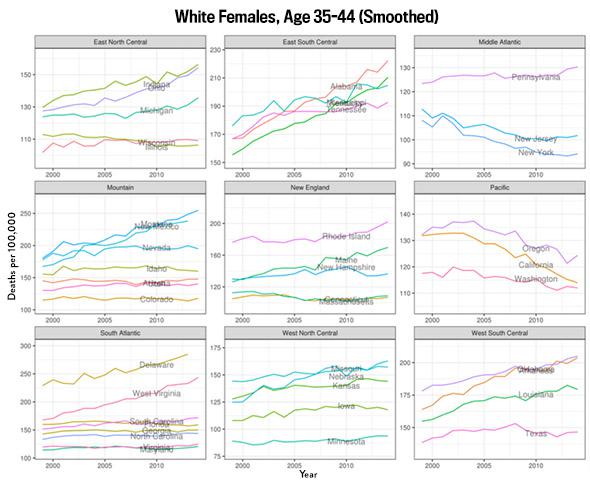

But look at these:

Jonathan Auerbach and Andrew Gelman

Flat in some states, sharp increases in others, and steady decreases in other states.

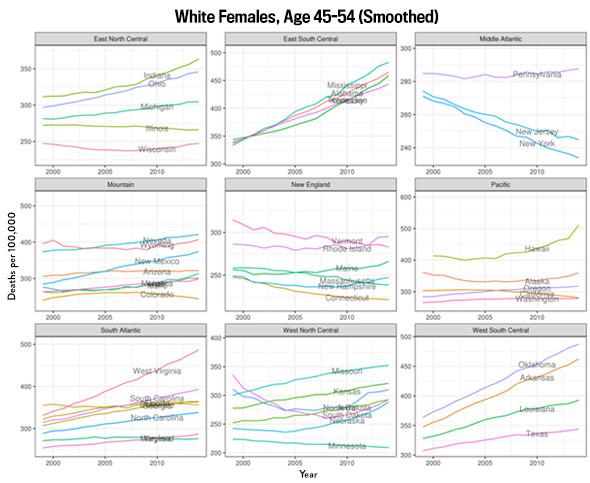

The patterns are even clearer here:

Jonathan Auerbach and Andrew Gelman

In their two papers on mortality trends, Case and Deaton have added a lot to the conversation on these issues. Our plots, showing trends by state, demonstrate in a very simple way that aggregate mortality trends are vague generalizations: There are many winners and losers over the last decade within white middle-aged Americans, or among any other particular group. There are also many relevant ways to slice up these trends, and it’s not clear to us that it’s appropriate to framing these trends as a crisis among middle-aged whites.

We see the role of statisticians such as ourselves to smooth the data and make clear graphs. Now it’s time to open the conversation to include demographers, actuaries, economists, sociologists, and public health experts such as Bound et al., cited above, and Chris Schmid, author of the paper, “Increased mortality for white middle-aged Americans not fully explained by causes suggested.” There’s lots to be found, much more than can be captured in any simple story.

Of course, there is one simple story the data does seem to confirm: Blacks still have significantly higher fatality rates than white Americans.* But that’s not news.

Correction, March 29, 2017: The original text of this article misstated that the last three sets of graphs show data from 1999–2004. They show data from 1999–2014. (Return.)

Update, March 31, 2017: This article originally stated that minorities have significantly higher fatality rates than white Americans. It was clarified to say that blacks have higher fatality rates. Mortality rates vary a lot among different minority groups, and there are age groups where some minority groups have longer life spans than white Americans.