An army of advocates for science will march on Washington, D.C. on April 22, according to a press release out last Thursday. The show of force aims to “draw attention to dangerous trends in the politicization of science,” the organizers say, citing “threats to the scientific community” and the need to “safeguard” researchers from a menacing regime. If Donald Trump plans to escalate his apparent assault on scientific values, then let him be on notice: Science will fight back.

We’ve been through this before. Casting opposition to a sitting president as resistance to a “war on science” likely helped progressives 10 or 15 years ago, when George W. Bush alienated voters with his apparent disrespect for climate science and embryonic stem-cell research (among other fields of study). The Bush administration’s meddling in research and disregard for expertise turned out to be a weakness, as the historian Daniel Sarewitz described in an insightful essay from 2009. Who could really argue with the free pursuit of knowledge? Democratic challengers made a weapon of their support for scientific progress: “Americans deserve a president who believes in science,” said John Kerry during the 2004 campaign. “We will end the Bush administration’s war on science, restore scientific integrity and return to evidence-based decision-making,” the Democratic Party platform stated four years later.

In 2016, Hillary Clinton’s campaign continued with the battle-tested plan. “I believe in science,” she announced to rapturous applause at the Democratic National Convention last July. But if that message played well to her base, it didn’t prove to be persuasive on a broader scale. The problem was, conditions for the combat over science have lately been transformed. Old alliances are shifting, and the science partisans who intend to march on Washington would be wise to understand the implications of this change. Today’s “war on science” could be a trap.

In the Bush years, there was every reason to believe that pro-science activism would be effective. For more than four decades, Americans had viewed scientists as deserving of respect. Even now, about 40 percent of adults profess “a great deal of confidence” in leaders of the scientific community, according to the General Social Survey; our faith in science is second, in this metric, only to our allegiance to the nation’s military leaders. (The executive branch of government, on the other hand, scores in the teens, and the press in single digits.) At the same time, more than 70 percent of Americans believe that the benefits of scientific research outweigh the harms, and almost 90 percent say that scientists should have at least a “fair amount” of influence over policy. In light of all this science boosterism, which has been quite consistent over time, it must have seemed clear that if the Democrats could brand themselves the Party of Science—if they could reframe political disputes as skirmishes between science and faith, or between evidence and belief—then they would have a way to outflank the GOP and capture some of its support.

But what had been a sharp-edged political strategy may now have lost its edge. I don’t mean to say that the broad appeal of science has been on the wane; overall, Americans are about as sanguine on the value of our scientific institutions as they were before. Rather, the electorate has reorganized itself, or has been reorganized by Trump, in such a way that fighting on behalf of science no longer cuts across party lines, and it doesn’t influence as many votes beyond the Democratic base.

The War on Science works for Trump because it’s always had more to do with social class than politics. A glance at data from the National Science Foundation shows how support for science tracks reliably with socioeconomic status. As of 2014, 50 percent of Americans in the highest income quartile and more than 55 percent of those with college degrees reported having great confidence in the nation’s scientific leaders. Among those in the lowest income bracket or with very little education, that support drops to 33 percent or less. Meanwhile, about five-sixths of rich or college-educated people—compared to less than half of poor people or those who never finished high school—say they believe that the benefits of science outweigh the potential harms. To put this in crude, horse-race terms, the institution of scientific research consistently polls about 30 points higher among the elites than it does among the uneducated working class.

Ten years ago, that distinction didn’t matter quite so much for politics. When Bush was elected in 2000 and 2004, he won among college-educated voters—the most science-minded people in the country. These people were most likely to be swayed by a Democratic “Fight the War on Science” pitch. In 2008 and 2012, the pro-science, went-to-college crowd turned around and voted for Obama, tilting in his favor by several points.

In this past election, the groups were realigned to match the anti-elitist fervor of the Trump campaign. Those with little education turned out to be the major source of Republican support. Among those who never went to college, Trump won by a margin of 8 percent, while Clinton held a 9-point edge among college grads. According to Pew Research, this was by far the widest education gap seen in exit polls going back to 1980. In a post-election analysis at FiveThirtyEight, Nate Silver found that Trump held a 31-point advantage in the nation’s least-educated counties, while Clinton held a 26-point advantage in the best-educated ones—and concluded that income explained only part of this effect.

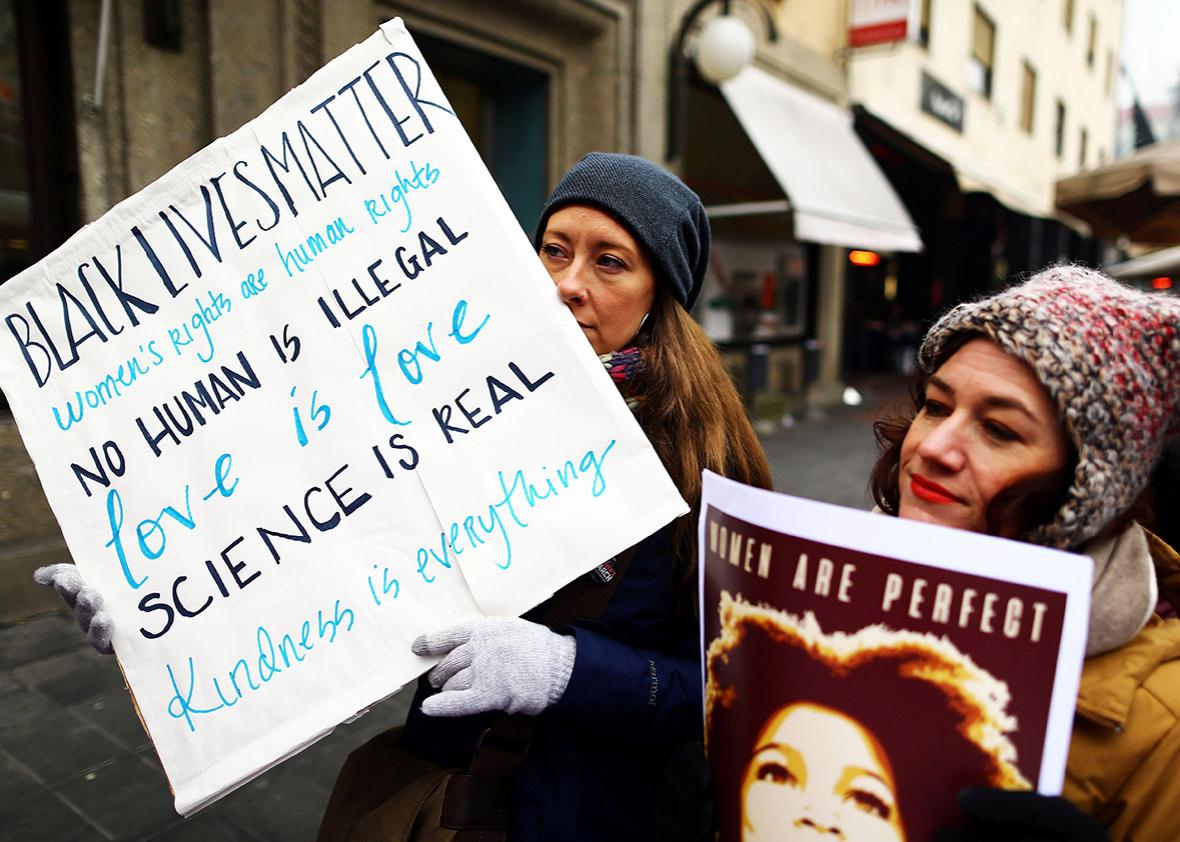

Thus we find ourselves in a position where America’s anti-science sentiment, such as it exists, has gathered behind a single candidate. Science partisans have noticed, too, and their “war on science” rhetoric has never been so frantic and intense. “Is Trump the most anti-science president ever?” asked Newsweek the day after the election. Other outlets have since then been cataloguing Trump’s most aggresive, anti-science moves and other warning shots that mark an epic war to come.

Yet the rise of anti-elitism as a political force makes this response riskier than it was before. A decade ago, a call to arms against the War on Science—and a science march on Washington—might have helped destabilize a right-wing coalition by signaling that Bush’s policies on, say, stem-cell research and birth control were outside the mainstream. But with the battle lines redrawn, the same approach to activism now seems as though it could have the opposite effect. In the same way that fighting the War on Journalism delegitimizes the press by making it seem partisan and petty, so might the present fight against the War on Science sap scientific credibility. By confronting it directly, science activists may end up helping to consolidate Trump’s support among his most ardent, science-skeptical constituency. If they’re not careful where and how they step, the science march could turn into an ambush.