When NASA began teasing a major announcement earlier this week about a great discovery “beyond our solar system,” it was clear that it was going to be something exciting. And in space, the most exciting thing is obvious: aliens.

It’s not aliens.

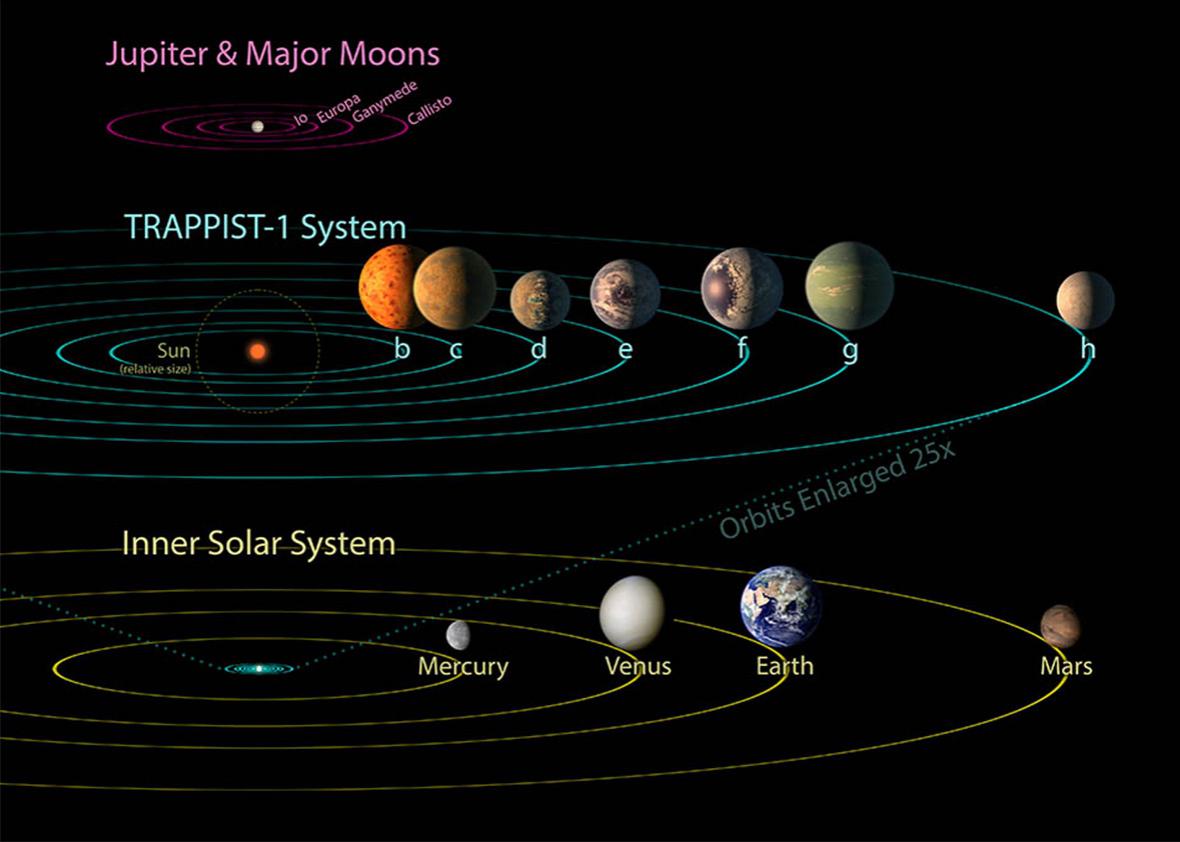

The space agency disclosed the discovery of Trappist-1, a system of seven Earth-size exoplanets orbiting a star about 40 light-years away. The scientists say it’s possible that all of those planets—the first-known and largest system of such worlds around a single star—could contain water, though it’s most likely on the three found in the habitable zone.

A detection including such terms as “Earth-size,” “habitable,” and “water” all contribute to the idea that we are getting ever closer to finding life elsewhere. And that means maybe aliens, right?

Technically, yes, it means maybe aliens. But not aliens where you think: As Quartz’s Akshat Rathi points out, it’s less likely that we find life on these specific planets anytime soon, but that this will help scientists learn how to better search in the future. Finding a bunch more planets of the right shape, size, zone, and temperature would greatly increase the odds of finding water—and life.

As Rathi writes:

The reason this is a big deal is not because scientists have found so many Earth-like planets at once. We’ve already discovered hundreds of those. Nor is it because Trappist-1 is so close. The star Proxima Centauri is only four light years away, and it too has an Earth-like planet in its orbit. The Trappist-1 solar system is a big deal because it’s going to be the test bed for accelerating our search for alien life.

What about this discovery will help us do that? For one, the (actual) star in this announcement is an ultracool dwarf that is about the size of Jupiter, much different than our star. Finding such a similar planetary system like ours around a (literally) cool star like this one—there are clues that the planets are rocky and tidally locked to the star—signals that scientists may want to start looking away from sun-like stars for extraterrestrial life.

NASA

Furthermore, scientists often discover the existence of exoplanets by observing how stars might dim as planets cross by in their orbits. Trappist-1’s star is much dimmer than most stars, which makes it easier to see the chemical signatures of these planets—like water or oxygen—using instruments like the ultrasensitive James Webb Space Telescope, which is set to launch in fall 2018.

So, not aliens yet. Of course, that doesn’t stop NASA from capitalizing on the thrill of the idea: The press release is accompanied with fantastic imagined sketches of the newly discovered planets. But don’t expect anything more Earth-like on them to pop up anytime soon.