Screw the “majestic” bison: Squirrels should be our national mammal. Love them or hate them, it’s impossible not to identify with them. One has only to toss a crumb on a college campus and watch as a squirrel scampers up, caught between an endless oscillation of curiosity and crippling social anxiety, to see the resemblance. O kindred spirit, so twitchy and so dear! But it turns out that squirrels may not just be as awkward as us: They also get frustrated like us, psychology researchers at the University of California–Berkeley have discovered.

Those familiar with these expressive rodents know how they let their anger be known: a guttural growl, a chattering of teeth, a stamping of feet. But the key to interpreting their emotions may also lie somewhere else: in the curve of their majestic, bushy tails. When confronted with a frustrating task, fox squirrels—close biological cousins of common gray squirrels, but the species more likely to hang out on Berkeley turf—arc and swish their tails to signal their displeasure, according to a study published last month in the Journal of Comparative Psychology.

In many ways, these campus squirrels make the perfect study subjects. With lifespans that can exceed 10 years, they are the ideal balance of wild and tame, unafraid of humans yet retaining many of the behaviors of their forest brethren (caching nuts, fleeing predators, etc). While their familiarity and resulting boldness with humans may make a study of campus squirrels harder to extrapolate to other species, it also makes them a breeze for researchers to train and interact with, says lead researcher and Berkeley psychology doctoral student Mikel Delgado. Specifically, they can easily be taught complex skills—for instance, how to open a box containing a delicious walnut.

Walnuts, you see, are the campus squirrel’s favorite food. (I always thought it was chocolate chip cookies, because of this one time a squirrel snatched an entire plastic-wrapped chocolate chip cookie from my hands while I was sitting at an outdoor café on the Berkeley campus. The squirrel then proceeded to squat on a nearby branch and eat the cookie in front of me while leering shamelessly. Though, upon further reflection, I remember that the cookie also contained … walnuts.)

So for the research, Delgado first tagged 22 squirrels with colored, nontoxic fur dye, so she could tell them apart. Then she taught them, over several trials, how to open a small black box. (The procedure was cleared by the university’s Animal Care and Use Committee.) She put the squirrels through trials in which they had to open boxes which could contain several things: a delicious morsel of walnut, a less-delicious kernel of dried corn, or nothing. Sometimes, though, she completely locked the box. Keeping other squirrels distracted via the cunning use of peanuts, Delgado videotaped the test squirrels as they attempted to open each type of box, documenting the signals they made in response to each result.

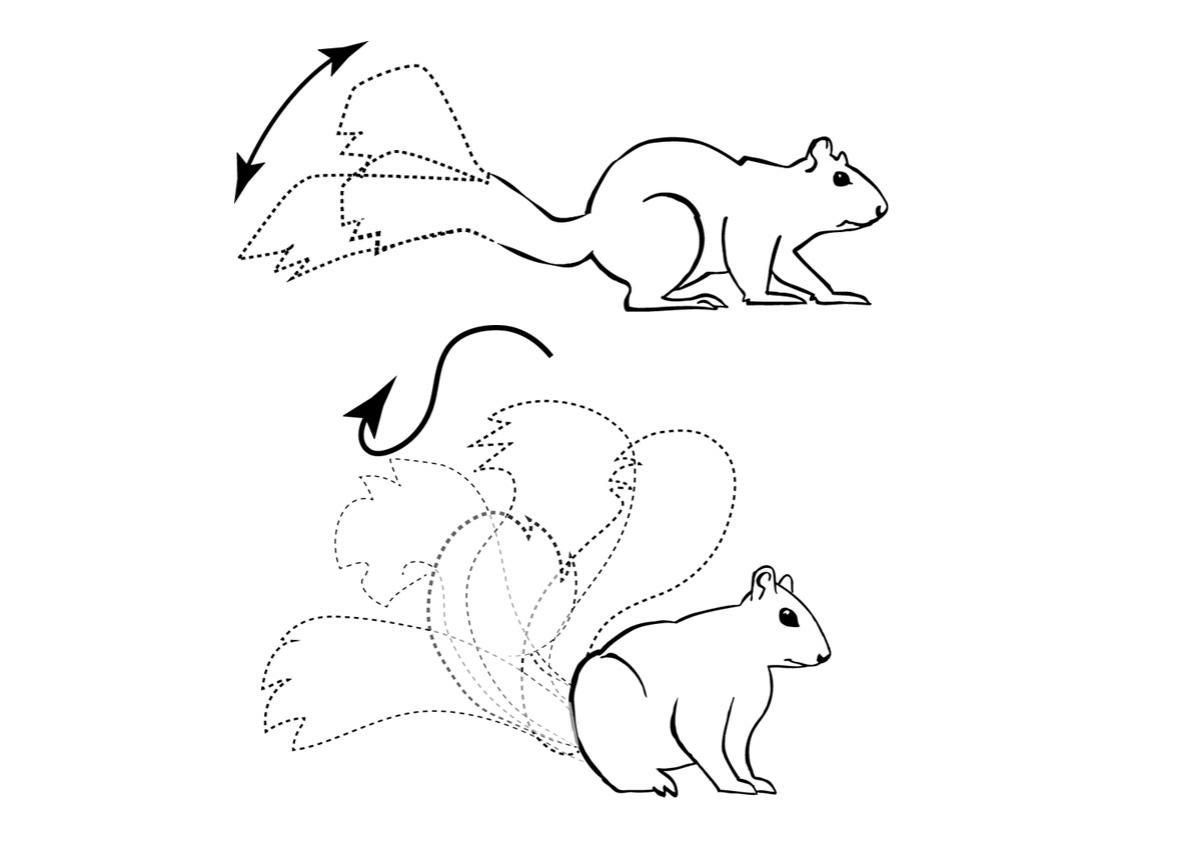

Viewing the tapes, Delgado found that the squirrels used a common signal whenever the box was locked or empty. Unable to text their friends “ugh,” “agh,” or “aw, nuts,” the squirrels responded to this cruel tease by utilizing tail “flags”—long, arcing movements of their majestic tails, compared to a more subtle twitch. Here’s a diagram of what a tail flag looks like (b) compared to the more common tail twitch (a):

Scott Bradley

Let’s clarify that when we talk about “frustration” in squirrels, we’re not referring to the same set of subtle and complex emotions that you or I might feel. Rather, we’re talking about a basic emotional response that happens when an expected reinforcement (in this case, a walnut) fails to appear—by definition, a frustrating experience.

Researchers still don’t know whether these tail flags are a way of communicating to other squirrels to “stay away,” or merely an outlet, perhaps involuntary, for their exasperation. This tail movement, after all, is not unique to frustration: It is the same motion a squirrel makes to signal general aggression—as when it is attacked by a predator, when another squirrel is stepping on its territory, or possibly when it is approached by a barefoot Justin Bieber.

“Is it frustration or agitation?” says Delgado. “That’s something that we’d really have to tease apart more to say.”

Tail-flagging behavior is typical for many species of squirrel, says Nina Vasilieva, a Russia-based zoologist who has published studies on the mating woes of yellow ground squirrels. In her years of research on yellow ground squirrels, she has usually seen this behavior when her subjects were anxious or excited. “But the problem of frustrating behavior in squirrels is [an] unexplored field,” Vasilieva says.

The Berkeley research, which was conducted over several months in 2011, involved just 22 squirrels. Many became too full or bored to complete multiple trials in different conditions, says Delgado, who was inspired to christen many with individual names reflecting their unique markings, including Flame, Leopard, Moon, Clementine, Streak, Quinn, Aggie, and Thunder. (Delgado told me she has studied Flame, her favorite, for four and a half years now. She jokingly refers to her as “my oldest friend in grad school.”) Small sample size is certainly a limiting factor in the study, especially when it comes to characterizing general squirrel behavior. “That’s the downside of working with wild animals,” says Delgado. “You have to just accept that some squirrels are going to quit before you finish.”

The study appears to be the first in which researchers intentionally frustrated wild animals by thwarting their expectations to see how they reacted. While it might be tempting for aspiring squirrel-whisperers to interpret such a study as a direct window into an animal’s emotional state, we should be cautious when it comes to thinking we can ever truly know what an animal is feeling. Obvious external clues are only one part of the picture, as I wrote last October in an article on TailTalk, an app that claimed to interpret your dog’s emotions through his tail. In fact, dog-cognition experts told me, tail-wagging is just one part of a complex ecosystem of signals that dogs use to communicate with their owners. Perhaps what these squirrels felt was not frustration but annoyance, disappointment, or a deep existential despair.

After all, despair is a condition inherent to being a squirrel, Delgado points out. Each year, they bury hundreds of nuts, only to find most of them gone or stolen by other squirrels when they return. Squirrels are the Sisyphus of the small mammal world, eternally pushing their boulders up the hill, only to watch them fall back down the following day. Given these conditions, “they seem to be pretty optimistic,” Delgado says, noting that many squirrels came back to try the box again even after they had been burned. This resilience, she says, could be a necessary trait given their environment. “You can’t let one setback ruin your life,” she says. “You’ve got to just keep being a squirrel.”