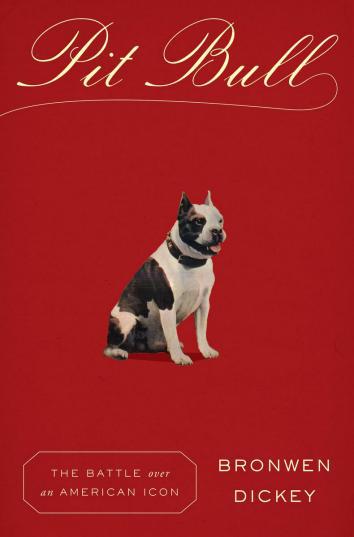

Excerpted from Pit Bull, by Bronwen Dickey, available now from Random House.

A month or so after Sean and I adopted Nola, I met a woman named Lori Hensley. We were standing in line at a local theater making casual conversation when she mentioned that she directed a local nonprofit called the Coalition to Unchain Dogs. The goal of the organization, she said, was to invert the normal paradigm of animal welfare. Instead of removing dogs from “bad” homes and placing them with “better” families, the group worked to improve the dogs’ lives in the homes they already had, thus preventing them from entering the overburdened shelter system in the first place. This was done by providing the dogs’ owners with basic veterinary care, spay/neuter surgeries, doghouses, and fenced play areas for their pets, all free of charge.

“You should come see what we do,” Lori offered. “We can always use more help.” I smiled politely and mumbled something lukewarm in response. As noble as the group’s objectives sounded, I did not consider myself an “animal person.” In truth, I found certain memes of humane activism (“I love animals, but hate people!”) to be alienating. I also never wanted to see another dog on a chain as long as I lived.

My family had owned nine dogs by the time I was 12. There were two dachshunds, two Scottish terriers, a golden retriever, a Boykin spaniel, a collie, and two mutts. None lived with us longer than a few years. Most ended up roaming the neighborhood, where one was hit by a car, or chained in the backyard, where one was strangled and died. All howled long into the night. Because of this, many of our neighbors viewed us with contempt: We were the family so irresponsible it couldn’t take care of its own pets.

What my neighbors did not know was that the suffering of the dogs outside our home was a symptom of the suffering inside it. My parents were highly intelligent, generous, and compassionate people, but they were cursed with crippling addictions that numbed their consciences, stunted their ability to make good decisions, and rendered them unable to deal with the responsibilities of everyday life. I was 6 years old when my mother first told me that she had a drug problem, 9 when she was arrested for cocaine possession, 12 when my father’s liver failed from years of drinking, and 15 when the failed liver finally killed him. All of us, including the dogs, were casualties of a remorseless disease. Shame and finger pointing did not solve that problem.

Rebecca Necessary

“Here’s what’s interesting, though,” Lori said before I was able to change the subject. “I don’t do this for the dogs. I do it for the people.” Then she mentioned, offhand, that roughly 80 percent of her clients owned pit bulls.

The first fence build I attended with Lori took place at the mobile home of a woman named Cheryl, who was pregnant with twins at the time. She and her boyfriend owned three pit bulls and a Chihuahua. Ten volunteers spent roughly two hours driving T-posts and pulling welded wire to complete the project. When Cheryl unhooked her dogs from their chains, they shook their giant heads, looked around tentatively, took a few shaky steps, then started to run, jump, and play for the first time in years, perhaps ever. Cheryl’s eyes brimmed with tears as though a crushing weight had finally been lifted.

I then began accompanying Lori on her outreach visits, during which she stopped in to see between 12 to 15 clients each Saturday. One family sat on garbage bags of secondhand clothing because they could not afford furniture. Their sewage emptied into the yard through a plastic pipe. Another constructed a sprawling tent city out of old shipping containers and a broken-down bus. Lori sat on porches and beside hospital beds, fussed over newborns, and admired family photographs. It soon became clear that dogs were only a footnote in a much larger community project. “If the coalition leaves any kind of legacy behind,” Lori said, “I hope that it is remembered as one of the first animal groups that cared as much about the well-being of the person as it did about the pet.”

Amanda Arrington, the woman who founded the coalition in 2007, initially focused on the problem of chained dogs as an animal welfare issue. She believed it could be ameliorated with the right resources— namely, free fences. When she and Lori began spending more time in the neighborhoods where chained dogs were most common, however, they found systemic social problems that went much deeper. The real enemy was not neglect or cruelty; it was poverty. Residents of lower-income communities—especially those in African American and Latino neighborhoods—simply did not have access to the same veterinary clinics, pet supply stores, and pet care information that other animal lovers took for granted.

This was greatly exacerbated by what the women felt was a “reverse Robin Hood” mentality in the traditional animal welfare movement that disparaged those who could not spend a great deal of money on their animals. Several of the coalition’s clients reported having their companions stolen by well-meaning rescuers who did not realize how much the dogs’ owners depended on them for emotional support. Other clients were afraid to ask shelter workers or animal control officers for help out of fear that their pets would be taken away. This is the gap the coalition worked to close. Since 2007, the group has unchained 1,885 dogs in eight cities and spayed or neutered almost 4,000 under Lori’s direction.

The person Lori visited most often was an 89-year-old woman named Doris. She had recently lost most of her right leg to a foot infection, so she wrapped the stump in a clean cotton sock and pushed herself around in an old manual wheelchair. Doris had lived alone since her husband died in 2000, but every morning she made her bed with crisp hospital corners, scoured her kitchen from top to bottom, and set her dining table for four—though no one ever joined her for dinner. In her youth, she worked in the curing barns of a company called Central Leaf Tobacco, where she said her boss would regularly ask her to leave work early so that she could “come along and clean the house” for his wife. On Doris’s right cheek was a thin scar that wound its way down to the top of her chest. She told me that many years ago, she tried to save her neighbor from being beaten by a drunken, raging husband. The man broke a whiskey bottle on the kitchen table and dragged it across Doris’s throat, nearly killing her.

Other than Lori and a few volunteers from Meals on Wheels, Doris had no regular visitors until the winter of 2012, when a sickly black pit bull wandered out of the woods behind her house. The dog was old, with nubby yellow teeth, flanks pocked with scabs and sores, and leathery teats that hung so low they almost touched the ground. Fingers of charred flesh ran down the sides of a giant burn scar that spanned the length of her back, and she moved slowly, as though dragging a large cinderblock behind her. Fearing that the dog would be put to sleep if she called animal control, Doris began cooking grits and eggs for her every morning and wheeling out to the front porch to keep her company. Soon the dog was sleeping in Doris’s kitchen, where she answered to a new name: Pretty Girl. If Doris knew or cared that Pretty Girl was a pit bull, she never said so. There was no fretting about “breed traits.” To Doris, Pretty Girl was just a dog.

Over time, I saw dozens of formerly scrawny animals like Pretty Girl transform into sleek, muscular family pets as the bond with their people intensified, but in most cases the bond had always been there; better resources just helped it thrive. “Nobody wants to keep their dogs on chains,” a client named Marlynda told Lori. But sturdy fences were expensive ($500 minimum) and required a great deal of physical work and special equipment to install. Fence recipients were so grateful to be treated with dignity, rather than scorn, that some became volunteers themselves, spreading information about pet health around their neighborhoods. The unlikeliest of these was a single father and former backyard pit bull breeder named Rodney, who became something of an animal welfare spokesman.

At a city council meeting in Durham, North Carolina, Rodney testified that in his neighborhood pets were suffering not because their owners were cruel and depraved but because the long history of inequality in those areas poisoned everything it touched, including the lives of animals. Referring to his own African American heritage, he drew a devastating parallel. “We used to be in chains,” he told the council members. “Now our dogs are in chains.”

Since it ramped up in the 1990s, the marketing of the pit bull as an icon of “urban edginess” has been incredibly effective. On some streets, every house contained a pit bull, if not two or three. No one I asked could pinpoint when the trend started or why, but it seemed to come down to two concerns: cost and safety. Few families who wanted a dog could afford to spend $500 to $1,000 on a purebred puppy, but pit bulls were always easy to acquire, if not completely free. A number of clients had tried to adopt dogs from local shelters but had been turned away, so they sought out a friend or neighbor whose dog had just given birth. Many other neighborhood pit bulls came from accidental litters or from the local flea market, where truck beds full of cheap puppies were available every weekend. The Great Recession of 2008 had left people even more desperate to make ends meet, and unlike other parts of the underground economy, dog breeding was legal and unregulated. A surprisingly large number of clients, mostly single moms and grandmothers, had taken in animals for friends or family members who lost their jobs, went to prison, or succumbed to terminal illnesses.

Random House

I met pit bulls that lived in overturned trash cans, in houses made from scraps of wood, in the beds of old trucks; pit bulls that lived with toddlers and with the bedridden elderly; pit bulls that shared close quarters with other dogs, pigs, horses, and chickens; pit bulls that loathed other animals and preferred to be with people. After several hundred of these encounters, I no longer thought of the dogs as belonging to any particular group, let alone a “breed.” The only thing they shared was that their presence was a comfort and an inspiration to the people around them, to whom the death of a dog (pit bull or otherwise) was mourned as much as, if not more than, the amputation of a limb.

Occasionally, I came across the canine bruisers everyone worries about, animals whose wiring just didn’t seem right, but each was off-kilter in a different way. Yes, I met two or three pit bulls with nasty dispositions, but also a German shepherd that furiously attacked its own legs when approached, a border collie I was certain would kill me if given the chance, a pug that launched herself at the necks of other dogs near food, and a chow that made even the sturdiest veterinarians cower.

As Dr. Laurel Braitman observes in her book Animal Madness, “Every animal with a mind has the capacity to lose hold of it from time to time. Sometimes the trigger is abuse or maltreatment, but not always.” Like ours, the canine brain is far more intricate than a simple nature-nurture “debate” can clarify. It can be thrown off-track by innumerable factors, including shifts in hormones and neurotransmitters, as well as injury and congenital birth defects. Also like us, many dogs that suffer from these maladies can improve with treatment, but, sadly, others cannot. Were the ill-tempered dogs I met born with their screws loose, or had a lifetime of stress mentally worn them down? There was no way of knowing. As one researcher I interviewed explained, “Nature versus nurture only exists in the media. Everyone in the sciences knows that it’s both.”

I was less surprised by the fraction of unstable animals than by how many dogs—from the smallest Chihuahuas to the most imposing Rottweilers—had endured years of deprivation and physical discomfort yet never lashed out at anyone. Dogs with intestinal blockages or collars embedded in their necks hardly raised a lip or bared a tooth when poked, prodded, or lifted into transport vehicles. It was a powerful testament to the affiliative nature of Canis lupus familiaris as a creature, something we too often look past in a culture so fixated on carnage. Even the most daunting, musclebound Presa Canario is, by virtue of its biology, predisposed to seek out attention from, and bond with, humans. That is yet another marvel and mystery of the dog: It is the only animal that will place our safety and survival above its own.

Excerpted from Pit Bull by Bronwen Dickey. Copyright © 2016 by Random House. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.