This article originally appeared in the Conversation.

I trampled clumsily through the dense undergrowth, attempting in vain to go a full five minutes without getting snarled in the thorns that threatened my every move. It was my first field mission in the savannahs of the Republic of Guinea. The aim was to record and understand a group of wild chimpanzees that had never been studied before. These chimps are not lucky enough to enjoy the comforts of a protected area, but instead carve out their existence in the patches of forests between farms and villages.

We paused at a clearing in the bush. I let out a sigh of relief that no thorns appeared to be within reach, but why had we stopped? I made my way to the front of the group to ask the chief of the village and our legendary guide, Mamadou Alioh Bah. He told me he had found something interesting—a few markings on a tree trunk. Some in our group of six suggested that wild pigs had made these marks while scratching up against the tree trunk; others suggested it was teenagers messing around.

But Alioh had a hunch. This man can find a single fallen chimp hair on the forest floor, and he can spot chimps kilometers away with his naked eye better than I can with expensive binoculars. So when he has a hunch, you listen to that hunch. We set up a camera trap in the hope that whatever made these marks would come back and do it again, so we could catch it all on film.

Camera traps automatically start recording when any movement occurs in front of them. For this reason they are an ideal tool for recording animals doing their own thing without any disturbance. I made notes to return to the same spot in two weeks (as that’s roughly how long the batteries last) and we moved on, back into the wilderness.

Whenever you return to a camera trap there is always a sense of excitement in the air of the mysteries that it could hold. Most of our videos consist of branches swaying in strong winds or wandering farmers’ cows enthusiastically licking the camera lens, but still there is an uncontrollable anticipation that maybe something amazing has been captured.

What we saw on this camera was exhilarating—a large male chimp approaches our mystery tree and pauses for a second. He then quickly glances around, grabs a huge rock and flings it full force at the tree trunk.

Nothing like this had been seen before and it gave me goose bumps. Jane Goodall first discovered wild chimps using tools in the 1960s. Chimps use twigs, leaves, sticks, and some groups even use spears in order to get food. Stones have also been used by chimps to crack open nuts and cut open large fruit. Occasionally, chimps throw rocks in displays of strength to establish their position in a community.

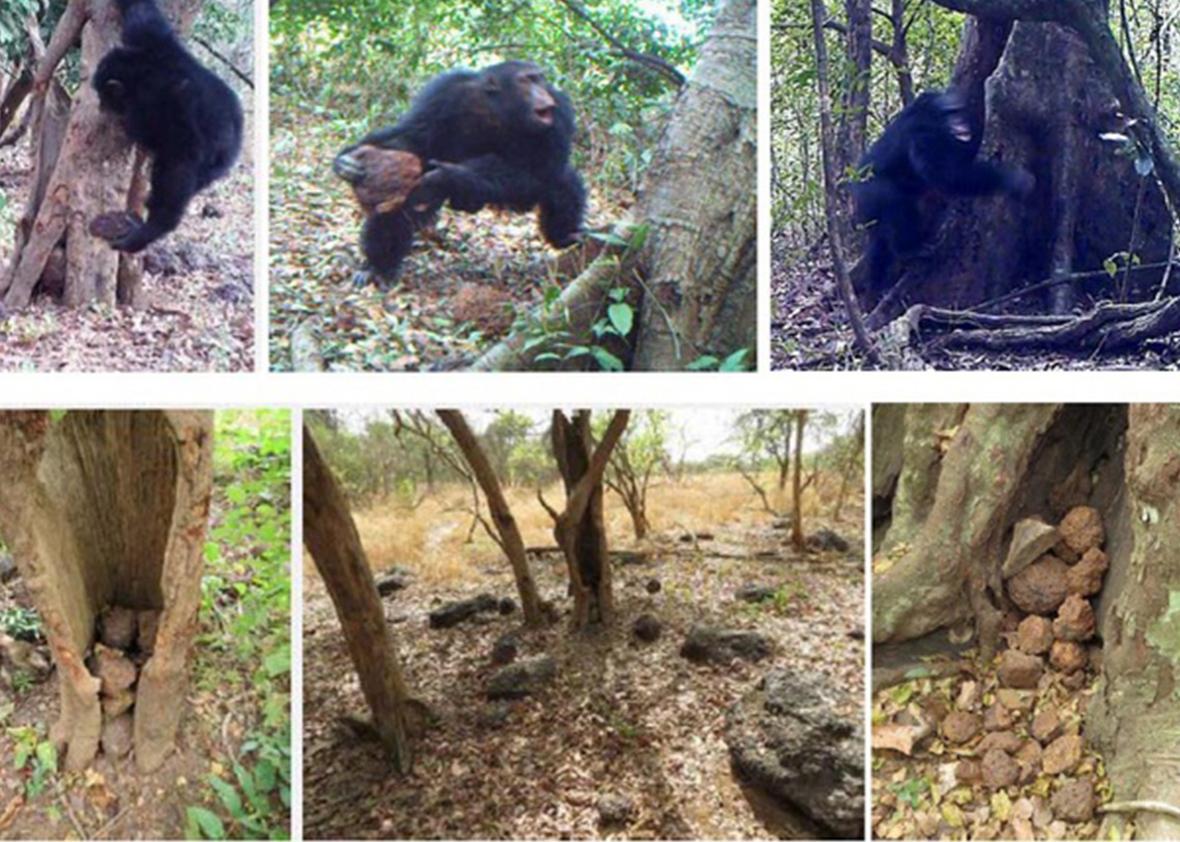

But what we discovered during our now-published study wasn’t a random, one-off event, it was a repeated activity with no clear link to gaining food or status. In other words, it could be a ritual. We searched the area and found many more sites where trees had similar markings and in many places piles of rocks had accumulated inside hollow tree trunks—reminiscent of the piles of rocks archaeologists have uncovered while studying early human history.

Videos poured in. Other groups working in our project began searching for trees with telltale markings. We found the same mysterious behavior in small pockets of Guinea Bissau, Liberia, and Côte d’Ivoire but nothing east of this, despite searching across the entire chimp range from the western coasts of Guinea all the way to Tanzania.

I spent many months in the field, along with many other researchers, trying to figure out what these chimps are up to. So far we have two main theories. The behavior could be part of a male display, to which the loud bang made when a rock hits a hollow tree adds emphasis. This could be important in areas where there are not many trees with large roots on which chimps would normally drum their powerful hands and feet. Trees that produce an impressive bang could accompany or replace feet drumming, and thus become popular spots for revisits.

On the other hand, the behavior could be more symbolic—and more reminiscent of our own past. Marking pathways and territories with signposts such as piles of rocks is an important step in human history. Figuring out where chimps’ territories are in relation to rock throwing sites could give us insights into whether the same idea applies to them.

Even more intriguing than this, we may have found the first evidence of chimpanzees’ creating a kind of shrine or “sacred” trees. Indigenous West African people have stone collections at sacred trees and such man-made stone collections, commonly observed across the world, look eerily similar to what we have discovered here.

Kühl et al (2016)

To unravel this distinction, and other mysteries of our closest living relatives, we must make space for them in the wild. In the Ivory Coast alone, chimpanzee populations have decreased by more than 90 percent in the last 17 years.

A combination of increasing human populations, habitat destruction, poaching, and infectious disease now endangers chimpanzees. Leading scientists warn us that, if nothing changes, chimps and other great apes will have only 30 years left in the wild. In the unprotected forests of Guinea, where we first discovered this enigmatic behavior, rapid deforestation is rendering the area close to uninhabitable for the chimps that once thrived there. Allowing chimpanzees in the wild to continue spiraling toward extinction will not only be a critical loss to biodiversity, but a tragic loss to our own heritage, too.

You can support chimps with your time, by becoming a citizen scientist and helping spy on their behavior at www.chimpandsee.org, and with your wallet by donating to the Wild Chimpanzee Foundation. Who knows what we might find next that could forever change our understanding of our closest relatives.