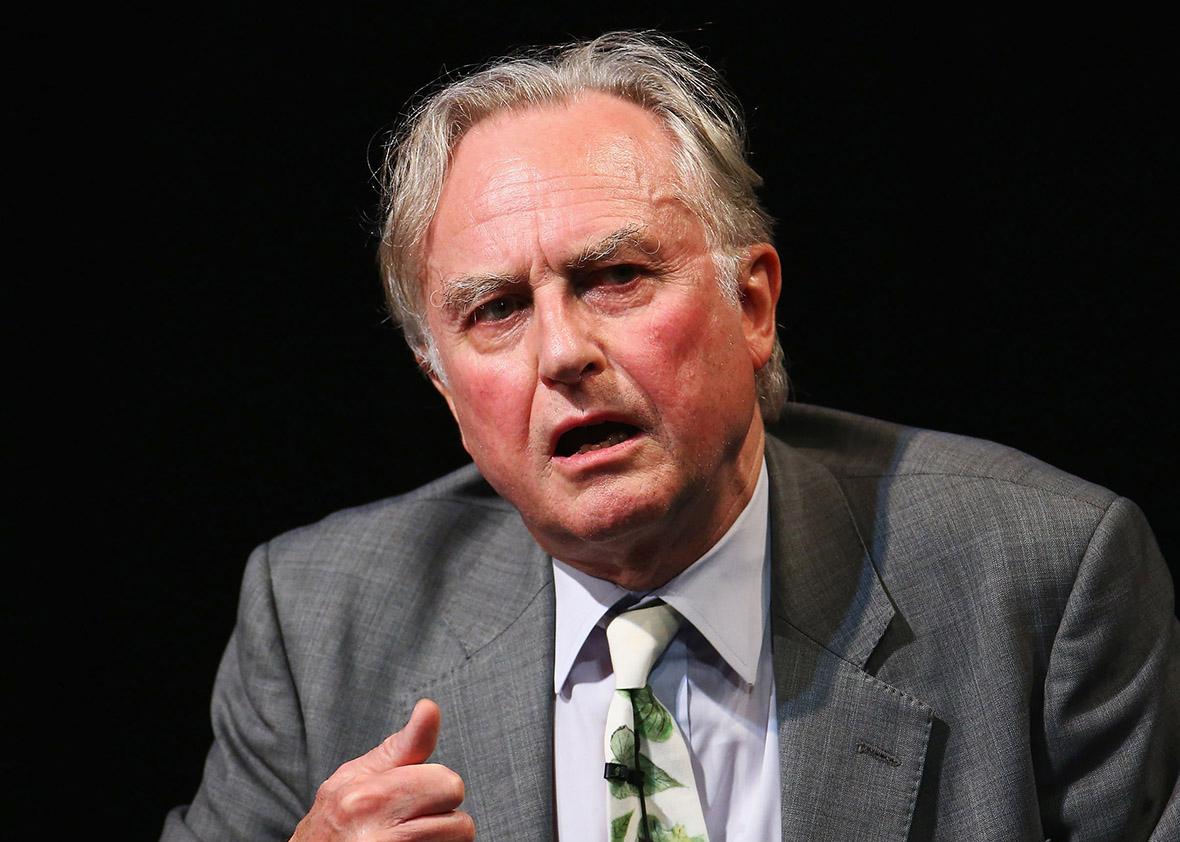

Richard Dawkins is not your garden-variety Internet troll. He’s a retired professor at Oxford University and the author of a number of well-received, best-selling books on science and atheism. His book The Selfish Gene is one of the most-read popular accounts of evolution, and it introduced the term “meme,” long before Internet cats, as a way to express how ideas spread and evolve. In other words, he’s as establishment as they come. He is no fringe conspiracy-monger lurking in the anonymous cave of message boards and comment sections.

But you’d be forgiven for thinking he is, based on his willingness to say offensive things on social media, often at the expense of non-famous people. In the latest iteration, he proposed the notion—just as a simple “what if”—that Ahmed Mohamed got himself arrested on purpose as a way to get money and attention.

Mohamed is the 14-year-old boy from Irving, Texas, who was arrested this month because he brought a clock he constructed to school. The school claimed the boy brought the clock to make people think it was a bomb, which he denies. He was interrogated without his parents or a lawyer present, which is against the law in Texas.

To most people, the arrest and interrogation of a geeky 14-year-old Muslim kid in a NASA T-shirt without any reasonable cause smacks of racism and Islamophobia (without even going into the legality). That’s the reason President Barack Obama invited Mohamed to the White House, many people donated to a college fund for him, and companies like Facebook and Microsoft sent him various gadgets and invitations. There’s even a Twitter hashtag: #IStandWithAhmed.

Then there is a different interpretation. Some, with false innocence, ask: What if Mohamed’s clock actually had been a bomb? (As many have pointed out, nobody ever believed he had a bomb, or else they would have called the bomb disposal squad.) The more conspiracy-minded ask: What if Mohamed’s father, who is a vocal advocate for ending Islamophobia, cooked up the idea to get media attention and money?

And that’s where Richard Dawkins enters the picture. The British scientist doesn’t dispute that the arrest was wrong (unlike the ostensibly liberal TV host Bill Maher), but he focuses on Mohamed’s behavior rather than that of the authority figures, drawing on some very dubious sources to do so, such as a YouTube conspiracy theorist who can’t even be bothered to spell Ahmed Mohamed’s name properly. In the weirdest instance, Dawkins even links to a piece at the right-wing hate-monger site Breitbart, thereby spreading a conspiracy theory the paranoid author espouses.

Remember, Dawkins is talking about a 14-year-old child. And not just any child: He’s part of an immigrant family, and a member of a racial and religious minority in a culture not always known for tolerance of others. In other words, Dawkins is punching down: His comments focused criticism on the most vulnerable figure in the case.

This isn’t the first time Dawkins has chosen the wrong end of a controversy. When Nobel laureate Tim Hunt faced justifiable criticism for making sexist jokes to his female hosts at a conference in South Korea, Dawkins saddled up to defend Hunt against “baying witch hunts.” Previously, he has made oddly sophist and insensitive comments about Down’s syndrome (saying it would be immoral not to abort a fetus with the condition), rape (comparing the relative harm of different types of rape), and pedophilia (contrasting “mild” and “violent” forms of abuse). When people challenge him on his behavior, he resorts to insulting their intelligence or reading comprehension, which you can see by following the Twitter threads in the links.

However, as the Ahmed Mohamed case shows, Dawkins is most belligerent on anything to do with Islam. He is no fan of any religion, but he has lumped the world’s 1.6 billion Muslims together as irrevocably violent. Dawkins also labels Muslims as scientific underachievers based on the number of Nobel Prizes awarded, though by that standard only a few nations in the world have produced any scientists of note. (Then there are the issues with the Nobels themselves.) He also has chided feminists for wasting their time addressing sexual harassment when women in predominantly Muslim nations face more difficult challenges, which managed to honk off a lot of people.

It would be easy to dismiss Dawkins as a crank, except that he’s an important figure in the popular communication of science, as well as a prominent voice among atheists. Many scientists and science writers cite The Selfish Gene as a major reason they chose their career path. His more recent anti-religion manifesto The God Delusion has given many atheists courage and a sense of community, despite the lack of cultural acceptance of atheism in the United States. College professors assign The Greatest Show on Earth to students as an eloquent and readable introduction to evolutionary theory. At his best, Dawkins is a powerful writer and advocate for science, at a time when evolution and climate change are still considered controversial by too many people.

That’s why the gulf between the often-charming persona of Dawkins the author and the often-bigoted curmudgeon of Dawkins on Twitter is troubling. If actor/writer George Takei is the Internet’s wacky, liberal uncle, Dawkins is the cranky, racist grandpa we try to ignore on Facebook. Many science communicators use social media to promote both public understanding of science and inclusion of underrepresented groups—Danielle Lee, Katie Mack, and Slate’s own Phil Plait, to name just three. Positive voices for science and diversity are out there. We don’t need someone trying to set the clock back on representation.

Dawkins has more than 1 million followers on Twitter, which means anything he says on that platform gets read by a lot of people. His tweets are frequently retweeted by hundreds of others, and people who criticize him are sometimes flooded with vitriolic responses from Dawkins’ fans, who defend everything he says. (I suspect I’ll hear from them in the comments and on Twitter.)

Dawkins’ blind spots about Islam, gender, race, and social behavior aren’t unusual (alas): They’re a laundry list of white male prejudices. However, they’re all the more visible and inexcusable because he claims to be a rational thinker. None of us are free of bias, and Dawkins, with his understanding of science, should recognize that our view of reality is distorted by our own mental framework and the societies we inhabit. There’s nothing rational about his comparing two bad things to downplay one of them (X is not as bad as Y, therefore X isn’t so bad) or his willingness to accuse a quarter of the world’s population of violence and uncivilized behavior. The best hope for any of us, especially someone like Richard Dawkins, is that with critical self-examination we can identify our own blind spots and compensate for them. Then maybe, just maybe, we won’t take to social media to air conspiracy theories involving 14-year-old boys.