The last thing anybody wants is more mosquitoes. The whining little bloodsuckers can spread viruses like dengue, West Nile, yellow fever, and chikungunya. We spray mosquitoes with pesticides, drain their swampy homes, and poison their young. We slather ourselves in foul-smelling repellants, sleep beneath gauzy nets, and even prime our immune systems with vaccines to fight the pathogens mosquitoes inject into us. But now scientists are taking a counterintuitive approach to destroying mosquitoes: release more of them into the world.

Just give them some bacteria first.

The scientists are basically engaging in biological warfare because of the pressing need to control Aedes aegypti. Thanks to its fondness for human homes and blood, this mosquito is one of several species that transmit West Nile virus, which has sickened more than 40,000 Americans and killed more than 1,700 since 1999, when it broke out in the United States. A. aegypti can also carry chikungunya virus, which in 2014 made its American debut in Florida and Puerto Rico. And this mosquito can carry dengue virus, which causes pain so severe in the muscles and joints that it’s nicknamed “breakbone fever.”

Before 1970, only nine countries had dengue outbreaks; now, more than 100 countries have endemic dengue. American cases mostly occur in Florida and Puerto Rico, where a 2010 epidemic sickened more than 10,000 people. Worldwide, the disease annually sickens 100 million people. Dengue fever kills 22,000 people every year, mostly in the tropical regions of Africa, southeastern Asia, and northeastern Australia. Despite dengue’s rapid spread in the past 50 years, we don’t have specific treatments or vaccines for it.

The fight against dengue is particularly urgent in Cairns, Australia, a city with about 150,000 residents on the country’s northeastern coast. “In Cairns,” says entomologist Scott Ritchie of Australia’s James Cook University, “we’ve had outbreaks every year since 1995”—with a high of 1,000 cases in 2009. To get these outbreaks under control, Australian scientists are trying to eliminate Aedes aegypti using the bacteria Wolbachia pipientis.

Approximately 65 percent of insect species are naturally infected with this bacteria, which lives inside the cells of an insect’s body and gets transmitted to all of an infected female mosquito’s young. But what’s intriguing is Wolbachia’s selfishness. The bacteria impairs the ability of viruses like dengue to replicate inside the mosquitoes, thereby reducing the pathogen’s spread in humans—in theory.

The idea of waging bacterial warfare with Wolbachia was originally proposed in the 1960s. In 1967, field experiments showed that the bacteria reduced the number of mosquitoes transmitting filariasis worms in Burma. More recently, Australian scientists in the Eliminate Dengue program are testing Wolbachia in field trials in Vietnam, Brazil, and Indonesia, as well as in Cairns’ southern neighbor, Townsville.

But Ritchie, his collaborator Ary Hoffmann of Australia’s University of Melbourne, and their colleagues opted to study an even more virulent form of Wolbachia called—believe it or not—“popcorn.”

Originally isolated from fruit flies, popcorn Wolbachia gets its name from its signature feature. When it burrows into an insect cell, it grows and reproduces until the cell resembles a container of stovetop popcorn that’s been overpopped. Unlike regular Wolbachia, popcorn reduces mosquitoes’ lifespans. The dengue virus, which a mosquito picks up when it feeds on an infected person, needs to incubate inside a mosquito up to 12 days before it can be injected into the next person—which means the popcorn Wolbachia should in most cases kill the mosquito before it lives long enough to spread the disease. This would be an improvement on regular Wolbachia, which reduces—but doesn’t eliminate—the chance a mosquito will spread dengue.

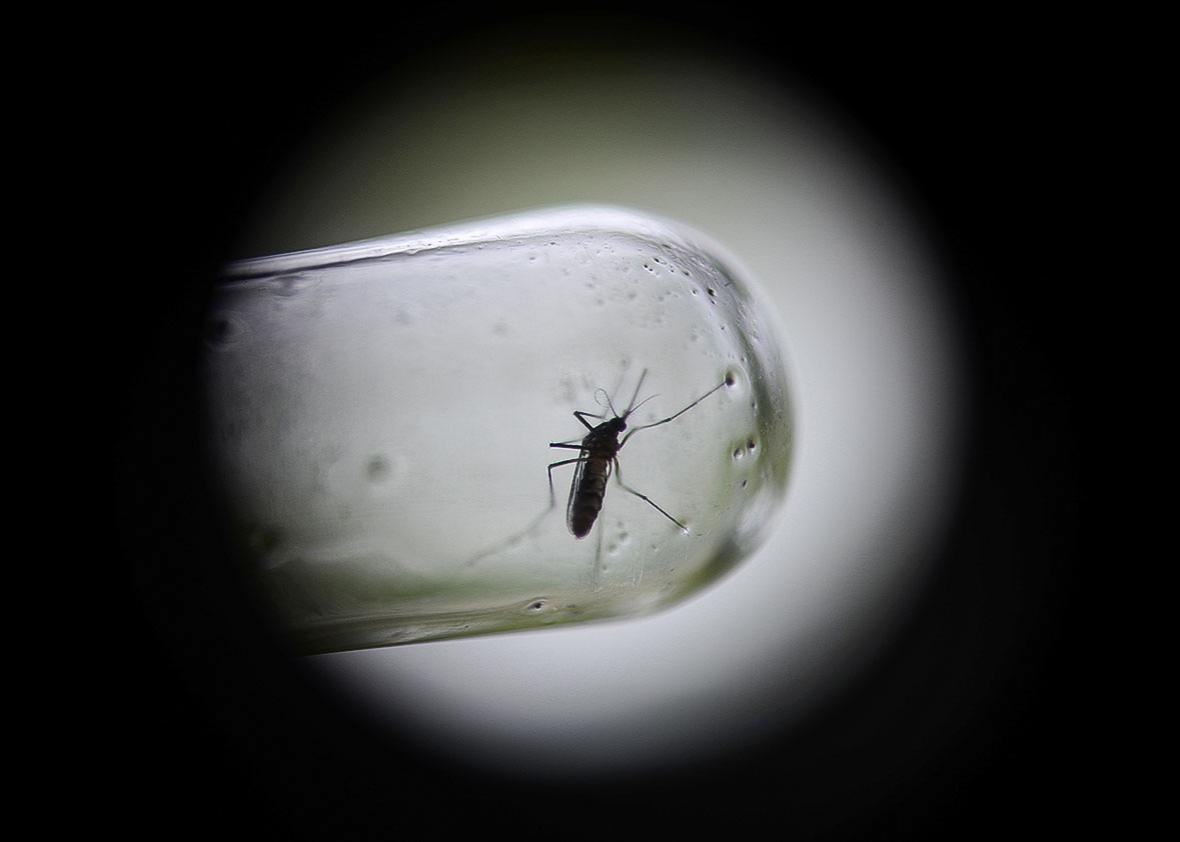

To figure out if popcorn Wolbachia could “fix” itself in a mosquito population—essentially become self-sustaining, like cold viruses among humans—the entomologists kept two colonies of adult mosquitoes in outdoor cages. Into one cage, they introduced 50 male and female mosquitoes infected with popcorn Wolbachia once a week. They did the same weekly routine in the second cage, except they introduced only healthy mosquitoes.

Ultimately, the entomologists found that it took four months of weekly releases to replace all of the healthy mosquitoes in a colony with infected ones. That sounded great to me, but Ritchie says that regular, less-lethal Wolbachia can fix itself into a wild mosquito population in two to three months. “The problem with popcorn,” he says, “is that it’s too good.” The popcorn Wolbachia was killing the adults before they could mate and have infected offspring—which is the key to how Wolbachia-infected adults replace healthy adults that can transmit dengue.

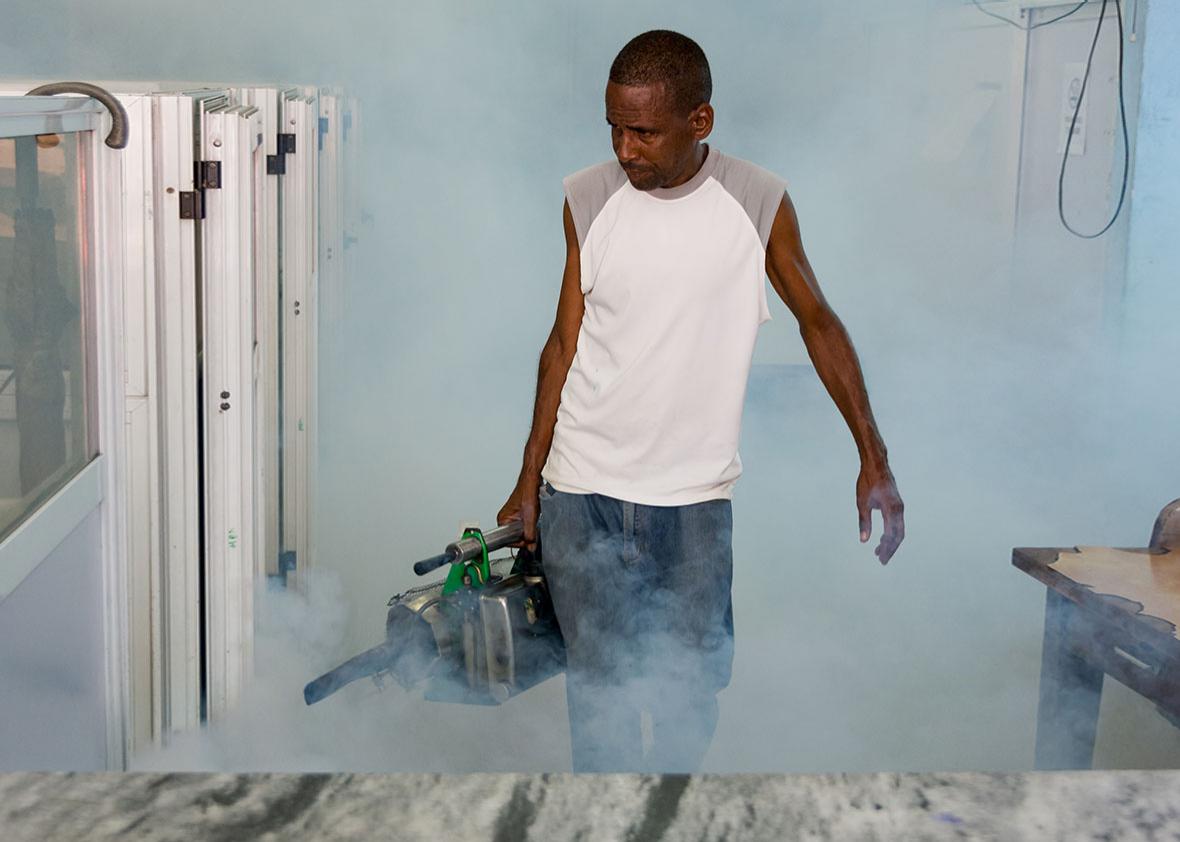

Whether researchers are using popcorn or traditional Wolbachia, there’s a practical problem with this approach: “It’s really expensive,” says entomologist and assistant professor Gabriel Hamer of Texas A&M University. “You have to have tons of infrastructure to rear these mosquitoes and release them as adults in huge numbers.” And this infrastructure and money could potentially have gone toward other, proven methods of controlling mosquitoes, like spraying insecticides.

Photo by Roberto Machado Noa/LightRocket via Getty Images

Furthermore, there’s the risk of negative public perception causing a backlash to this approach, as well as to other strategies such as genetically modifying mosquitoes. In the 1970s, public opposition closed down trials by the World Health Organization to control mosquito populations with radiation-sterilized male mosquitoes in Delhi, India.

However, Ritchie suggests that small, geographically isolated communities—like the Galápagos Islands or Key West, Florida—could use popcorn Wolbachia to eliminate their A. aegypti mosquitoes. But he cautions that his study is a “proof of concept” demo and that popcorn Wolbachia needs field trials before it can be actually deployed.

Hamer also has reservations. “It’s so hard to go from conceptual, theoretical, this-should-work to a field trial” that actually demonstrates less human disease, he says. “So far, with all these Wolbachia efforts around the world, I haven’t seen any overwhelming success stories.”

But while entomologists might disagree on the immediate usefulness of Wolbachia to eliminate mosquitoes, I am confident that they—and every other human at risk for West Nile, chikungunya, and dengue—can agree on one thing. Whether through bacterial warfare, spraying, or just swatting the little bloodsuckers into submission, we all have the same goal: fewer mosquitoes, less disease.