The first archaeological subdivision in America has a simple premise: The owner of each roughly 35-acre plot is guaranteed that his or her property contains archaeological sites. The covenants of the homeowners association allow residents to excavate on their land under the supervision of a professional archaeologist. Most of the sites are between 800 and 1,500 years old, and they include everything from some of Southwest Colorado’s earliest signs of agriculture to impressive stone architecture to evidence of cannibalism.

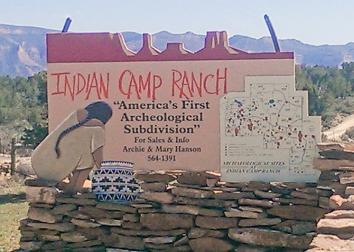

The pricey development, called Indian Camp Ranch, advertises its archaeological richness as a selling point. When I heard about the subdivision from a friend in the area, I was highly skeptical. Privatized archaeology made me picture skeletons moldering in storage sheds, ancient pottery displayed on coffee tables, and well-intentioned but clueless amateurs damaging irreplaceable sites as a recreational activity.

Photo by Nick Romeo

At first blush, Indian Camp Ranch seems like a spectacularly bad idea—a 21st-century revival of a dubious and destructive tradition. A little more than a century ago, visitors to what is now Colorado’s Mesa Verde National Park enjoyed excursions sometimes called “shovel picnics,” during which they followed lunch with indiscriminate looting of priceless archaeological sites. Before Theodore Roosevelt signed the Antiquities Act of 1906, this was perfectly legal, and after 1906 it remained one of the primary methods by which illustrious East Coast museums accumulated collections of Ancestral Puebloan artifacts from the Southwest.

Recreational pot hunting in and around Mesa Verde, though illegal on public land, was popular well into the 20th century; a contract archeologist from the region told me that Sunday outings in search of artifacts were still common in the 1960s. Mesa Verde is only about 20 miles from Indian Camp Ranch; both lie inside Montezuma County in the southwest corner of Colorado.

Archaeologists estimate that the population in this region at the height of the Pueblo III period in the 13th century was roughly equivalent to the population today: 25,000. The sizable population of the Mesa Verde region between the years 600 and 1300 A.D. means that a tremendous number of artifacts and remnants of structures still lie beneath and often above the surface of the land. Indian Camp Ranch boasts the highest recorded density of archaeological sites in Colorado; Canyons of the Ancients National Monument, which it borders on the west and south, contains approximately 100 sites per square mile.

Collecting artifacts on public land is now illegal, but if wealthy, largely white populations can still scoop them up recreationally on private land, how much has actually changed?

Photo by Lee Russell/Library of Congress

My first assumption about Indian Camp Ranch was that its residents had managed to bring shovel picnics right into their backyards. They could now avoid the effort of scouring steep rock canyons for artifacts and instead simply saunter out the back door with a cup of coffee and grab whatever they liked amid the sagebrush and juniper.

But as I spoke to archaeologists and residents of Indian Camp Ranch, the complexities of the politics, science, and ethics of preserving archaeological materials in the Southwest modified my perspective. After some investigation, I was almost convinced that Indian Camp Ranch was a model that offered the best hope for saving the material record of past cultures. Almost, but not quite.

* * *

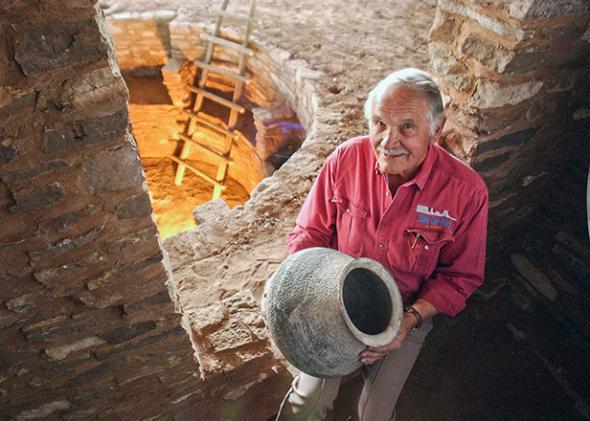

“I’ll show you a restored Indian village in the backyard,” 88-year-old Archie Hanson told me one morning after inviting me into his home at Indian Camp Ranch. Hanson is the founder and developer of ICR, and he and his wife, Mary, quickly pop up in any conversation about the subdivision. Archie wrote the rules that govern excavation at ICR, and he is adamant that they are strict, comprehensive, and sufficient to protect the development’s archaeology. The sizable collection of Ancestral Pueblo pottery prominently displayed in their living room suggested that the rules might be somewhat casual when it came to curation and storage, but I wanted to withhold judgment, and Hanson wanted to tell me about his life.

When he was a boy in the 1930s, Hanson loved collecting beads, fishhooks, arrowheads, shells, and any other tangible relics of the Native American tribes that once inhabited the California coast where he lived near Long Beach. Throughout a prosperous career as a California land developer, he continued amassing an amateur collection, flying a helicopter along his private stretch of coast and landing to grab artifacts. In the late 1980s, he and Mary became interested in the archaeology of Southwest Colorado after taking a river rafting trip guided by three archaeologists associated with the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, a nonprofit institute located next to ICR that is dedicated to research and public education. Mary loved picking up beads and arrowheads as much as Archie did, but on this rafting trip someone was always admonishing her to put them back down. “Finally I said to Archie, ‘Let’s get 10 acres so I can do what I want,’ ” Mary told me. “Here they believe in property rights,” Archie added. “You can dig up skulls and throw ’em over your shoulder.”

Photo By Lyn Alweis/the Denver Post via Getty Images

Spending time around archaeologists introduced them to the idea that particular objects are not exotic talismans to be snatched and hoarded, but rather units of data that acquire meaning only in aggregate and in context. Land in Montezuma County was cheap in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and the original plan of buying 10 acres expanded dramatically to an ultimate size of 1,200 acres for all of Indian Camp Ranch. “I really respected archaeology,” Archie told me, “but I was doing a development here. So how do you treat ground that contains ruins respectfully?”

His first step was to establish precisely where the ruins were located. Scatters of artifacts on the ground surface and standing stone wall and tower bases were suggestive, but he hired local archaeologist Jerry Fetterman of Woods Canyon Archaeological Consultants to do a comprehensive survey of the 1,200 acres before deciding where to place roads, power and plumbing lines, and building sites. Once the more than 200 ancient sites were identified and marked, he zoned the land so that none would be disturbed.

The primary building materials for Archie and Mary’s home reveal a more typical fate for archaeological ruins on private land in Montezuma County. Their 4,000-square-foot home is made from ancient stones salvaged from the rubble of towers, kivas, and houses built by Ancestral Puebloans. Archie found farmers in the nearby town of Dove Creek dumping stones after clearing standing Ancestral Pueblo architecture from their fields. He bought the rubble from the farmers and hauled it back to his plot at Indian Camp Ranch. The rocks that give his house structural integrity were used as building material roughly 1,000 years ago.

Sometimes destruction by private landowners happens when farmers clear fields before planting crops, but sometimes they give looters access to their land in exchange for a flat fee or a percentage of profits from the sale of artifacts. The executive vice president of Crow Canyon, Mark Varien, told me that letting looters demolish a site often fulfills two needs: one actual and one perceived. Landowners can make a bit of money, though the sums are usually modest. But looting also alleviates the fear that the government will seize their property and declare it a national resource. In reality, seizure is incredibly unlikely; while the Antiquities Act does grant the government discretion to acquire land to protect certain archaeological resources, this power is rarely exercised.

Destroying archaeological sites, digging up artifacts, and unleashing looters are all completely legal on private land in Colorado. In Greece, Mexico, and many other countries, archaeological resources on private land have the legal status of national property. Though U.S. laws vary somewhat by state, they generally protect sites only on federal and state lands. One exception is a Colorado state law that requires the notification of state authorities when human remains are found on private land. But the law is incredibly difficult to enforce because it relies on self-reporting by landowners.

Such looting and destruction cause losses that are both scientific and something closer to spiritual. “A site is like a text or a book, so removing these objects is like tearing pages from a book that is the record of these people’s culture,” Varien said. It’s a basic axiom of archaeology that context is everything; pottery in a certain spot may indicate the types of activities performed in the area, what foods people were eating, when the site was occupied, and a host of other information. Looters essentially convert scientific and historical data into vaguely exoticized art objects.

But the scientific loss is only one dimension of the problem. Crow Canyon supervisory archaeologist Caitlin Sommer described the spiritual aspect like this: “No human buries another human with the hope that one day those remains and grave goods will be dug up.” Native communities, such as the Hopi and Zuni tribes, who identify as descendants of the Ancestral Puebloans, often experience the disturbance of old graves as a kind of desecration. That such activity is often perpetrated by descendants of the settlers who stole land from tribes throughout the 19th century makes the insult worse.

Varien has approached private landowners throughout his career and tried to dissuade them from looting or bulldozing the archaeological sites on their property. He’ll knock on front doors and talk to guys in backhoes and make an idealistic case about common human heritage and the irreversible losses caused by hasty, amateur excavation.

He has never been able to persuade someone to stop demolishing architecture or selling artifacts from sites on their land.

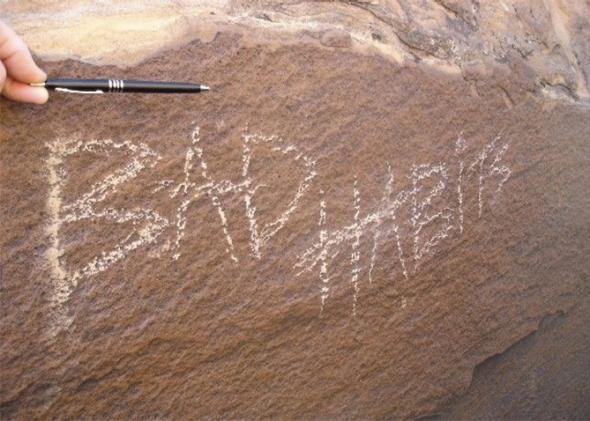

Even on federal land, where archaeological materials enjoy much stronger legal protections, the vastness and remoteness of the terrain, and meager budgets for ranger patrols, make enforcement incredibly difficult. The ancient rock art of the Four Corners region is a vivid reminder of pervasive modern vandalism; scattered among petroglyphs that are thousands of years old, you often see bullet holes and the carved initials of lovers.

Photo courtesy Bureau of Land Management

Against this backdrop, Indian Camp Ranch appears progressive. The sale of artifacts from ICR properties is strictly prohibited. All excavations must be supervised by a registered professional archaeologist, and reports from excavations must be published and made freely available for research. Though the covenants that bind landowners are difficult to enforce, Archie Hanson believes they help create an ethic of stewardship in the subdivision. And the explicit emphasis on archaeology as a selling point is designed to attract a self-selecting group dedicated to protecting fragile cultural heritage.

Hanson initially expected that ICR landowners would be eager to excavate. But most have not sponsored digs; the cost is often considered prohibitive. A thorough scientific excavation of a kiva—a circular subterranean structure likely used as a living space and for communal gatherings, and entered through the roof—might take an entire year, and expenses accumulate at every phase: salaries for archaeologists, lab fees for tree ring dating and carbon-14 tests to give the age of the site, mitigation efforts to protect the site from exposure to the elements. Hanson says he has spent more than $1 million preserving, excavating, and restoring the archaeological sites on his 39 acres. The roof he installed over the restored village in his backyard cost $100,000 alone. He thinks these lofty sums might have discouraged other landowners, who figured there was no cheaper way to excavate.

But Hanson’s restored village arguably demonstrates that an expensive excavation and restoration is not necessarily precise or responsible. “We had to invent the windows,” Hanson told me as we walked through the village. The area was only dirt and rubble when he bought the lot, though standing walls up to 24 inches were visible. He wanted windows in the restored buildings, but he didn’t know where they would have been located, so he guessed.

Photo by Nick Romeo

The site now has three fully excavated kivas, one from about 700 A.D. and the other two dating from between 1025 and 1134. There’s also a stone tower and several room blocks that were likely used for processing corn. An original mano and metate, a pair of stones used for grinding, lay on the dirt floor of one room. Hanson thinks about 50 people once lived here.

One of the handymen who helped at the excavation pointed to the tower as Hanson was showing me around and said: “We put a loft in there for shits and giggles.” Hanson nodded; fanciness seemed to be as much of a design principle as accuracy. “It’s great fun,” he said, “to think you can have your own ruin. I wouldn’t do it if I couldn’t have fun with it.” He also defended his right to make guesses: “Everything archaeologists do is a guess. If you’re sitting around a campfire with a beer, your guesswork is just as good as anybody else’s.” This was a surprising remark; why require the supervision of trained experts if all guesses are essentially equal?

The discrepancies continued to accumulate; he lined a kiva with mortar stones even though it would have been dirt-walled originally. He also mentioned that parts of the project were abandoned before completion. “Mary said to me, ‘Think of all the money we’re spending, we could go to Europe!’ So I said, ‘OK, Mary, no more.’ ”

Archie made several comments that reflected a casual attitude toward enforcing the landowners’ covenants he designed. “People violate it, yes, but do they hurt anything? Heavens no.” His view was that the incredible density of artifacts in the area made it unimportant if a few slipped off Indian Camp Ranch now and then in the pockets of visiting friends and family.

Photo By Lyn Alweis/the Denver Post via Getty Images

Archie and Mary had hosted a gathering of friends the night before I visited, and Archie mentioned that he had just given the same tour the previous evening. This suggested a new way to understand his village: not as a careful work of archaeology and reconstruction, but as a source of cocktail party conversation.

It was hard to see Archie Hanson as a hero of preservation. But however fanciful his reconstructions and unsettling some of his comments, he wasn’t exactly a villain either. Varien told me that professional pot hunters were using heavy equipment here before Hanson bought the land. Without his development, the archaeological sites on the 1,200 acres would almost certainly have been destroyed, looted, or churned over by plows. ICR didn’t always work perfectly in practice, but the subdivision had made it possible for landowners to protect and study the ancient history of the region.

One of Hanson’s neighbors at ICR, Jane Dillard, has allowed Crow Canyon archaeologists to excavate on her land for long periods of time. Excavation under the auspices of Crow Canyon costs a landowner nothing; it does, however, impose strict excavation protocols. Archie’s reconstructed village, for instance, would be an impossibility. Crow Canyon also typically refills the sites that it excavates, a policy that Archie said “killed him.” Backfilling the sites is a protective measure to preserve them for posterity, and arguably one that’s far more effective than even Hanson’s $100,000 roof, which still allows wind, rain, foot traffic, vegetation, and animals to damage the site. Throughout the tour he gave me, his cat and one of his dogs played freely on and among the reconstructed ruins.

A great kiva on Dillard’s property offers an interesting contrast to the restored village in Archie’s yard. Archaeologists believe that the great kiva, which dates to the Basketmaker III period (approximately 500 to 750 A.D.), probably functioned as a space roughly equivalent to a modern community center or town hall. The structure was dug on Dillard’s land over the last four years according to Crow Canyon protocols. The excavators were archaeologists from Crow Canyon and closely supervised members of the public—from middle school kids to senior citizens—who participate in Crow’s educational programs.

Photo courtesy crowcanyon.org

Dillard became interested in Southwest archaeology as a participant in one of these programs. She bought a plot in ICR in 1993, and she has lived there year-round since 2000. As part of her agreement with Crow Canyon, she has signed away any claims of ownership over the artifacts found during the excavation. Whereas Archie engages in the “great sport” of reconstructing pots with Elmer’s glue, the artifacts from Dillard’s land are being analyzed in Crow Canyon’s laboratory and entered into the Crow Canyon database. They will eventually be curated at the nearby Anasazi Heritage Center.

Dillard used to feel the temptation to pick up sherds of pottery and lithics while walking on her land. The ineffable charisma of ancient objects is what draws many participants to Crow Canyon; it’s even what initially attracts some archaeologists to the field. Of course it’s also what keeps looters in business; if there were no market for Ancestral Pueblo pots on eBay, the financial incentive for pot hunters would evaporate.

The challenge, then, is not to simply eradicate this feeling, but to channel it in useful directions. Only through education does the romance-of-objects motive gradually morph into an interest in broader questions about settlement and habitation, use and abandonment, landscape and political organization. Dillard still walks her land with her head angled down so she can spot artifacts, but the desire to pick them up has vanished after 15 years of volunteering at Crow Canyon and interacting with archaeologists.

Photo by E. A. Santiago with permission from Jane Dillard

After a year of living in Montezuma County, I’d noticed something similar happening to me. At first I would always ask my partner, who is an archaeologist, if I could pick up artifacts when we went hiking. (The answer was always no.) After hearing her explain a number of times why this was not a good idea, I started to see how someone could move beyond this fixation with the tangible.

People want artifacts to remain undisturbed for various reasons. Scientists might use the density of artifact distributions as a key to locating and understanding subterranean sites. Descendant native communities, by contrast, might object to the political implications of having their ancestors’ jewelry, hunting tools, or kitchenware collected as primitive curiosities.

The strength of the Indian Camp Ranch model is also its weakness: It relies entirely on the cooperation and understanding of landowners. Any particular landowners can refuse access to institutes like Crow Canyon, or they can design whimsical approximations of the past in the style of Archie Hanson. And while both of these outcomes do occur, Jane Dillard offers a third alternative. Only about 25 percent of the great kiva on her property was actually excavated. The rest was left untouched in case future archaeologists eventually develop superior technologies that make today’s techniques look as crude and destructive as the shovel picnics of the late 19th century.

Partial excavation is a powerful gesture of intellectual humility, a recognition of how primitive our techniques might look to unborn observers, but it also has a certain justness that goes beyond scientific pragmatism. As I walked with Dillard through the clumps of sagebrush and pinyon on her land, she pointed with a walking stick to a small sliver of red pottery. She stooped down to pick it up, held it out for me to see, then replaced it where it was. “We’ve disturbed you enough,” she said. “I’m going to leave you here.”