Paleolithic, vegan, raw, fruitarian, gluten-free, macrobiotic. Whatever diet it happens to be, the first question I ask is: “For the love of God, what’s going on?” I mean that literally. Because despite a veneer of scientific rhetoric, food fads are ultimately about devotion to dogma; religion, not science. The appeal of modern diet gurus lies in their promise of nutritional redemption—and resisting that appeal depends on our ability to recognize and dismiss the irrational basis of their authority.

It’s true that as a religious studies professor, I’m prone to analyze cultural practices in terms of religion. But with eating habits, the evidence is everywhere. Once, at a farmers market, I asked a juice vendor whether her product counted as “processed”—a vague, unscientific epithet that gets thrown around in discussions of what we should eat. After a moment of shock, she impressed upon me that processing fruit into juice doesn’t result in processed food. Only corporations, she insisted, were capable of making processed food. Not only that, but it wasn’t the processing that made something processed, so much as the presence of chemicals and additives.

Did the optional protein powder she offered count as a chemical additive, I pressed? A tan, gaunt customer, eager to purchase her cleansing smoothie, interrupted us. “It’s easy,” she said, staring at me intensely. “Processed food is evil.”

At least she was honest. Processed food is evil. Natural food is good. Evil foods harm you, but they are sinfully delicious, guilty pleasures. Good foods, on the other hand, are real and clean. These are religious mantras, helpfully dividing up foods according to moralistic dichotomies. Of course, natural and processed, like real and clean, are not scientific terms, and neither is good nor evil. Yet it is precisely such categories, largely unquestioned, that determine most people’s supposedly scientific decisions about what and how to eat.

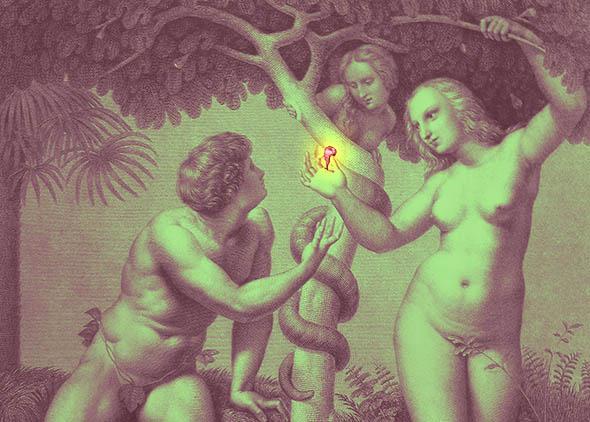

We’ve been primed to think this way. After all, the world’s most famous myth recounts a dietary fall from grace. Long ago, humans lived in an organic, all-natural, divinely designed garden, free from pesticides and GMOs and processed grains and sugar. But one day an evil advertiser came along and hissed, “Just eat this fruit.” Bam! Suddenly we were cursed with mortality, marital strife, labor pains, and agriculture.

Secular variants on the Eden myth are common in rationalizations of food fads. Adam and Eve get replaced by indigenous tribespeople or traditional Greek islanders, all of whom remain in the proverbial garden, lean and healthy and blessed. In its most recent incarnation, Paleolithic man is the culinary hero, and instead of disobeying God, we modern grain-eaters sin by disobeying the law of evolution.

Superstitious and unscientific food beliefs—the focus of my book, The Gluten Lie: And Other Myths About What You Eat—feature prominently in the research of Paul Rozin, a psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania. Rozin is best known for coining the phrase the omnivore’s dilemma—which food writer Michael Pollan popularized as the title of his 2006 best-seller—and he has written extensively on how we perceive what we eat.

“It’s an immense problem,” Rozin told me in an interview, with the exasperated air of someone who must repeatedly explain a self-evident truth. “Love of nature, it’s like a religion. You can show that natural pesticides, whatever that means, are more dangerous than artificial ones, but it doesn’t matter. No one will believe you.”

The phenomenon that Rozin describes isn’t unique to nutritional nonsense. Vaccine refusal (with its clear relationship to paleo and anti-GMO narratives of paradise past) depends on faith in what amounts to a religious ideology, complete with an evil deceiver—big pharma!—and the promise of salvation through avoiding unnatural chemicals. Unfortunately, research consistently shows the futility of combating ideologically motivated belief with facts and reasoned argument. No matter how well you make your evidence-based arguments, your vegetarian friend will continue to believe that avoiding meat cures cancer, and your gluten-free aunt will insist that eating bread causes Alzheimer’s. (It doesn’t. Celiac disease, however, is a rare but serious condition that can be managed by avoiding gluten.)

Dissuading nutritional zealots—like any zealots—seems hopeless. And it might well be, if we continue to focus on the effects of confronting them with evidence. But in my experience, there’s another solution—one that doesn’t depend on providing more evidence, but rather on changing how people evaluate the evidence they’ve already got.

In a recent viral essay for Gawker, Yvette d’Entremont (aka the Science Babe) called out food activist Vani Hari (aka the Food Babe) on her “bullshit.” While d’Entremont makes effective use of science, the heart of her criticism is philosophical. Some highlights:

- Failure to define terms: Hari never specifies what she means by “toxin” and “chemical.”

- Bad logic: If a substance is dangerous in one context, Hari assumes it must be dangerous in all contexts.

- No interest in dialogue: Detractors are banned from the Food Babe’s Facebook page.

It takes a decent background in statistics and biochemistry to understand how Hari tortures studies to fit her agenda. Thankfully, spotting the fatal flaws in her arguments requires no scientific knowledge whatsoever. Anyone with a rudimentary grasp of rhetoric and logic who reads The Food Babe Way will be overwhelmed by tautologies, fallacies, non-sequiturs, and false dichotomies.

It’s not just Hari. Consider Rozin’s “love of nature,” which is used to justify virtually every diet on the market, from gluten-free (modern Frankenwheat is unnatural!) to raw food (cooking is unnatural!). It turns out that the “appeal to nature” is a well-established fallacy, plagued by question begging—natural things are good because unnatural things are bad—in addition to the inherent vagueness of the term natural. Nevertheless, people demand all-natural foods and dutifully avoid unnatural chemicals, oblivious to the irrational foundation of their preferences.

Or take this utterly irresponsible anecdote from neurologist David Perlmutter’s forthcoming Brain Maker: “Consider Jason, the 12-year-old boy with severe autism who could barely talk in full sentences. In chapter 5 you’ll read about how he physically transformed into an engaging boy after a vigorous probiotic protocol.”

Like so many diet gurus and faith healers, Perlmutter (best known for the best-seller Grain Brain) routinely exploits another well-established fallacy, known as post hoc ergo propter hoc: If Event B follows Event A, then Event A must have caused Event B. The same fallacy often contributes to parents’ belief that vaccination led to their child’s developmental delays.

Strangely, the philosophical training that helps to identify pseudoscientific bullshit is largely absent from the American educational system. We pay lip service to critical thinking skills, but high schools rarely offer courses in formal logic. The vast majority of college graduates don’t understand the difference between induction and deduction. And it’s entirely possible for you to graduate with a degree in chemistry yet remain unfamiliar with thinkers like Descartes and Bacon whose philosophical innovations paved the way for your knowledge.

Study of persuasive techniques is also missing from the curriculum. Unless my students happen to take a class on Aristotle, it’s a good bet they’ll never learn to distinguish between pathos (appeal to emotion), ethos (appeal to character), and logos (appeal to logic). This leaves them especially vulnerable to nutritional evangelists, who, like their religious forebears, are heavy on pathos and ethos, but woefully lacking in logos.

At this point it would be nice to rest my case. Since food fads are based on irrational ideology shot through with terrible reasoning, I’ve proved that the antidote to food fads is teaching people logic and rhetoric. But as any good philosopher would no doubt object, the argument is seriously deficient. I assume that teaching these skills is possible, but some cognitive scientists have claimed it really isn’t. I assume that knowing about fallacies makes people less likely to accept fallacious reasoning, yet I provide no empirical evidence to support my claim. And I assume that basing dietary decisions on mythic narratives is inherently undesirable, without ever explaining why people who don’t are better-off.

Wait a second. What am I doing? I mean, everyone knows that diet gurus are way more persuasive than philosophers. Better to imitate the Food Babe if I want to convince people, right? Besides, I’ve got my own book to sell. Here goes:

We are facing an epidemic of idiocy. Dr. Oz dispenses the nation’s most popular medical advice. The Clintons’ personal doctor compares the Food Babe to Martin Luther King. Clean eating has given birth to new, horrific eating disorders. It’s enough to terrify anyone who cares about the mental health of our country and our children. Fortunately, there’s a simple cure! Unlike today, ancient civilizations such as the Greeks trained their children in logic and rhetoric. As a result, everyone thought rationally and no one held unjustified beliefs. Food Babes and grain brains were unheard-of. People ate all the gluten they wanted without a care in the world. Incredibly, the reduced stress meant they lived longer and never suffered from neurological disorders like Alzheimer’s and ADHD.

Let’s follow their lead. I promise: With just 10 days of researching logical fallacies and rhetorical techniques, you’ll be on the road to wellness! It may give you a headache at first, but don’t worry. That’s just the toxic beliefs leaving your brain. Before long you’ll feel like a brand-new person, capable of laughing at the latest nutritional dogma and eating your dinner in peace.

Trust me—I’m a doctor.