A woman breezes ahead of you on an airport walkway looking like a page out of Vogue. What is it about her, you wonder as you drag your squeaking roller-bag with a hoodie tied around your waist, that makes her so exquisitely fashionable? The classic cut of her blazer? The Mandarin collar on her silk shirt? That vented trench coat with welt pockets? Well, that certain je ne sais quoi has now been sewed up by science. Specifically:

Fashionableness = -.50m2 + .62m + .49 where m = matching z-score.

Or put another way: Don’t be too matchy-matchy.

That’s the conclusion a team of researchers led by psychologist Kurt Gray arrived at after conducting a pioneering study of the sad question confronting the sartorially challenged each morning: What exactly makes an outfit fashionable? Of course, we perceive clothing as chic for many reasons, not the least of which has to do with whatever Maisie Williams or Ryan Gosling wore to the Best People on Earth Awards. But Gray and his team hypothesized that there must be some pattern underlying our aesthetic preferences.

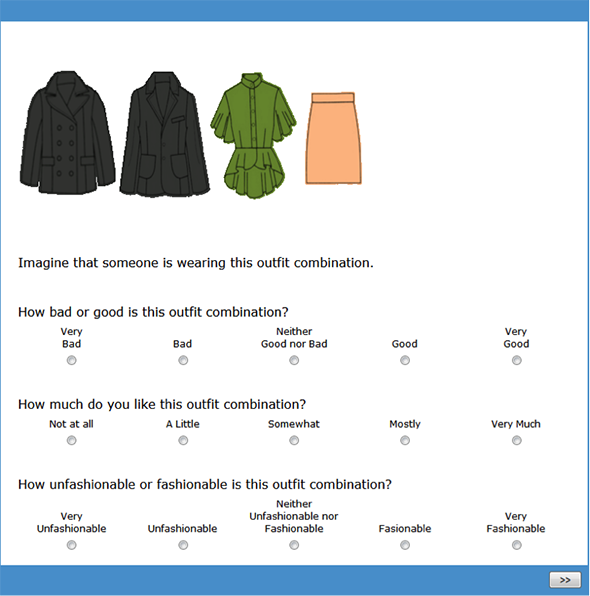

The researchers began with an essential (and measurable) element: color. Participants were shown various pairs of color combinations using images of separates—pants, skirts, tops, and coats—and were then asked to rank whether the combination was good or bad, how they felt about it, and how fashionable it was on a scale from Welcome to the Dollhouse (“very unfashionable”) to Anna Wintour (“fashionable”). The team’s goal was to uncover the relationship between how well-matched an outfit was and how much people liked it.

Courtesy of Kurt Gray, et al.

Across genders, researchers found these preferences follow an inverse U-shaped curve: Participants unsurprisingly recoiled from combinations that were seen as “clashing,” but they also balked at “matchy-matchy” outfits that reeked of desperate overplanning.

In other words, there is a sweet spot in the middle of the color-coordinated spectrum where you add just enough individualistic flair to hint you are the kind of person who collects vintage Japanese textiles or appreciates records on vinyl, but not so much as to ignite suspicion you are on your way to a cosplay convention. As the saying goes: Too much rosemary spoils the soup.

While this conclusion may seem intuitive, the authors point out that the impulse to find a balance between simplicity and complexity—known more broadly as the “Goldilocks principle”—is rooted “in a tradition of philosophical thought stretching back a millennia.” In other words, those catty, but pathologically well-coordinated, judges on Project Runway may actually be adherents of Buddha’s middle way, reflexively achieving sartorial enlightenment while we plebes continue to struggle with the question of whether feather earrings might be “a bit much.”

The most surprising thing about this study, however, may be that it’s the first of its kind. The fashion industry is worth $1.7 trillion (more than twice as much, the authors would have you to know, as the U.S. federal science budget), and the way we dress has a real and significant impact on our everyday lives. Studies have shown that the choices we make at the threshold of our closets can determine our job chances, whether we make a positive first impression, and how we perceive ourselves. So why has science shunned questions of style? It may have to do with the inherent difficulty in sorting through a confusing number of variables, from cut to texture to pattern (not to mention the attractiveness of the wearer) that affect our conceptions of fashion. But it’s also related to the age-old stigma fashion carries of being a superficial pursuit. Studying style, Gray admitted when we talked by phone, is often viewed as not sciencey-sciencey.

“Even though this is something that matters so much to our everyday experience, people often think that everyday experience is maybe too obvious to be studied empirically,” said Gray. When their study was being vetted by peer-reviewed journals, his team ran up against is this really science? skepticism, and he argued strongly that, “yes, science is a method, and we are applying this method to something that is a really important facet of human behavior.”

Gray does preach moderation, however, in interpreting the team’s conclusion; standout fashion sense still requires more courage than flair. “I think [moderation] is a good heuristic if you’re clueless about fashion and don’t want to look like a fool at that conference,” Gray explained. But “if you’re a fashion ninja, you should feel free to break any rules you want. In fact, many people say that the best fashion are ones that break the rules slightly—just like anything.”

Needless to say, most of us aren’t fashion savant Tavi Gevinson and could use some help. Which in turn raises the question: Is there an app for this? (“This” meaning “helping the fashion clueless.”) Not yet, but I did bounce some ideas around with one of the study’s co-authors, Nina Strohminger. Like, wouldn’t it be cool if you could scan your pants into your phone in the morning, hold up potential mates, and any top deemed a stylish enough match would trigger the song “Hot Stuff” by Donna Summer?

The possibilities of iCloset notwithstanding, the team does intend to keep illuminating the science behind fashion dos and don’ts. Future studies will seek to incorporate more complicated fashion stimuli from everyday life and to discern whether the Goldilocks principle, as it pertains to fashion, is universal across cultures and over time. Strohminger wonders whether our moderate color-matching preferences aren’t even specific to fashion at all, but are instead based on fundamentals of visual cognition that could just as easily apply to designing a room or painting a picture.

Personally, I am relieved that science is finally on the fashion case. As a sufferer of a rare sartorial form of Tourette syndrome, I find myself powerless to resist wince-inducing accessories. For some people, the middle ground between clashing and matchy-matchy is the size of Wyoming. For others, it’s more like a like a high wire strung above a Cirque du Soleil stage. So while Gray et al. get to work on defining “moderate,” you can find me hanging out with my kind of people on the Norwegian curling team’s pants Facebook page, discussing why “clashy-clashy” isn’t a thing.